Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies (21 page)

Read Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies Online

Authors: Ross King

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Architects, #History, #General, #Modern (Late 19th Century to 1945), #Photographers, #Art, #Artists

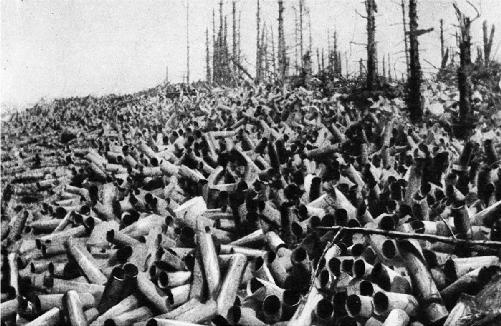

Spent shell casings at Verdun, with the ravaged woods in the background

Three weeks later a young German soldier outside the French fortified city of Verdun, 140 miles east of Paris, wrote a letter to his mother: “There’s going to be a battle here, the likes of which the world has not yet seen.”

7

His prediction was to prove appallingly accurate. On February 21, according to legend, the sword carried in the outstretched arm of the allegorical figure of the Republic in the

Marseillaise

relief on the Arc de Triomphe broke off—an ill omen if ever there was one. At seven o’clock that morning the ground along the western front began to tremble. Over the next few hours, hundreds of thousands of German shells rained down on the French lines at Verdun. After the bunkers and trenches collapsed under the relentless barrage, the German Fifth Army advanced through the wreckage of craters, wielding flamethrowers.

A German aviator, having looked down on the scene of devastation, reported to his commanding officer: “It’s done, we can pass, there’s nothing living there anymore.”

8

Verdun in ruins, 1916

Famously, the Germans did not pass: “

Ils ne passeront pas

” (“They shall not pass”), first uttered by General Nivelle, became the defiant French rallying cry. But the cost in human life was immense. “Our losses have been great,” reported

Le Petit Parisien

.

9

This statement must have made for shocked and sober reflection among regular readers, coming as it did from a prowar newspaper that for the past eighteen months had been a tirelessly optimistic cheerleader, specializing in what became known as

bourrage de crâne

(brainwash).

Le Petit Parisien

had been reporting, for example, that the French soldiers “laugh at machine guns” and that they looked forward to battle “as to a holiday. They were so happy! They laughed! They joked!”

10

But now there was no laughing or joking. If Verdun fell, Paris would follow and France would be lost. As an American in Paris later remembered, the first days of the Battle of Verdun were “the darkest days of the war.”

11

*

A WEEK AFTER

the Battle of Verdun started, Monet looked out his bedroom window to see his garden covered in snow. The sight put him in a wistful mood. Years earlier he had loved painting in the snow. In 1868, on a frigid day in Étretat, he had bundled himself into three overcoats and lit a brazier to warm himself as, hands protected by gloves, he painted a scene of snowbanks streaked in blue and mauve shadows. In Argenteuil in the winter months of 1874 to 1875—a season when snow fell in great quantities the week before Christmas, people sledded through the streets of Paris, and urchins threw snowballs at passersby

12

—Monet painted eighteen canvases of roads, houses, towpaths, and the railway line under blankets of snow. One of them showed people under wind-buffeted umbrellas fighting their way through snow flurries along a path beside the railway station toward where Monet was sitting with his easel, braving the elements. But by 1916, at seventy-five years of age, suffering from rheumatism and prone to chest problems, he was no longer fit for such wintry heroics. “Alas, by this time I am no longer of an age to paint outdoors,” he wrote to the Bernheim-Jeunes, “and despite its beauty it would have been better had the snow not fallen and therefore spared our poor soldiers.”

13

Monet worried about several poor soldiers in particular, but when Michel arrived home on leave in March, having “seen some terrible sights,” Monet peevishly complained that his son’s presence “singularly upset my calm and regular way of life.”

14

He continued to cope with the inconveniences and anxieties of wartime as he always did: by working frantically on his paintings. “I am so obsessed with my infernal work,” he wrote to Jean-Pierre, “that as soon as I awaken I rush to my large workshop. I leave only to eat lunch and then work until the end of the day.” He then discussed the newspapers with Blanche—“a great support to me”—before retiring to bed. “In this horrible war,” he continued, “what is there to say but that is too long and odious, and that we need victory. It is a sad life that I lead in my solitude.”

15

As usual, Monet was exaggerating his solitude. He braved the Zeppelins in the early months of 1916 to make several trips to

Paris—although the primary motivation was medical rather than social: his teeth had overtaken his eyes as a source of bother. Since the completion of his new studio he had been suffering from “terrible sore teeth, abscesses and inflammations.”

16

These problems necessitated multiple trips to the dentist. Nonetheless, Monet’s painful teeth did little to curb his gourmandizing as he sought to coordinate his sessions in the dentist’s chair with the dates of the Goncourt lunches. “If you’re planning on inviting me to the next Goncourt lunch,” he wrote to Geffroy in April, “I’d be very much obliged if you let me know the date as soon as you possibly can, since my poor teeth mean I shall have to come Paris frequently.”

17

One of Monet’s other preoccupations at this time was with charities for wounded soldiers and their families. One year earlier, he donated several of his paintings to be won at raffles, purchasing 200 francs’ worth of tickets himself.

18

In February 1916 he donated a painting to be raffled in aid of a charity providing clothing to French prisoners of war. He also began a correspondence with Madame Étienne Clémentel, wife of the minister of commerce and industry, regarding donations of his works for the benefit of an orphanage. Monet was eager to participate, but Madame Clémentel unfortunately wanted a drawing from him—“and I never do drawings,” as Monet explained to her, “that’s not my way of working.” He therefore offered instead “a modest painted sketch,” assuring her that it would “definitely be easy to sell for the benefit of the orphans.” In the end, Madame Clémentel and the orphans were the beneficiaries of two pastels of the Thames, which Monet personally journeyed to Paris to deliver.

19

Monet unquestionably did his bit for the war effort. However, he may not have been entirely altruistic with his donation to Madame Clémentel’s charity. It would not have escaped his notice, one day before he offered the modest sketch, that Madame Clémentel’s husband had persuaded Auguste Rodin to sign a document donating his works to France so that his Paris home, the Hôtel Biron, could be transformed, at state expense, into a museum dedicated to his honor. Rodin was in the process of consecrating himself in museums. He already

enjoyed dedicated museum space in London and New York. In the autumn of 1914 he had donated twenty of his sculptures, then on exhibition at South Kensington Museum (the present-day Victoria and Albert Museum), to the British nation “as a little token of my admiration for your heroes.”

20

Two years earlier, the Rodin Gallery had opened at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, with forty of the master’s works on display, including a twenty-seven-inch-high bronze cast of

The Thinker

. This large collection of works—bronzes, marbles, terra-cotta, plaster, drawings—had been donated to the museum by the French government, by the millionaire businessman Thomas F. Ryan, and by Rodin himself. Now Rodin was about to achieve further immortality through the creation of a museum in his name in a magnificent mansion in the heart of Paris, across the street from the golden dome of the Invalides.

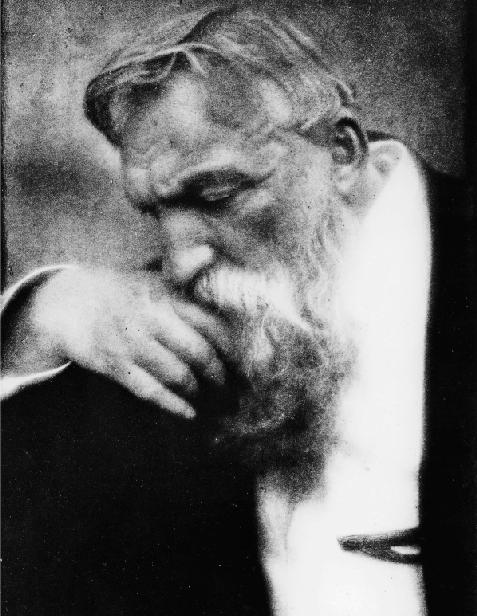

The sculptor Auguste Rodin

Monet had been one of the supporters of the plan for a Rodin museum at the government-owned Hôtel Biron—where the sculptor had been renting space since 1908—as soon as it was first mooted.

21

He and Rodin were old friends, and his career had in some ways been closely linked to Rodin’s. The two artists had been born in the same year—not on the same day, as was often claimed, but only two days apart. They found success around the same time, too: at a joint exhibition at the Galerie Georges Petit during the Exposition Universelle in 1889. Monet showed 145 works in the spacious rooms, which were interspersed with Rodin’s massive sculptures—some of which, to Monet’s irritation, Rodin placed directly in front of Monet’s canvases, blotting them out. When Rodin caught wind of Monet’s distress, he raged: “I don’t give a damn about Monet, I don’t give a damn about anyone, I only care about myself!”

22

The two men patched up their differences, and the exhibition was a wild

success that set both men on the road to fame and riches. “The same sense of brotherhood,” Rodin once wrote to Monet, “the same love of art, has made us friends forever.”

23

Not even Monet possessed the same grandiose sense of self-importance as Rodin, a man who, while in Rome a year earlier, informed the French ambassador that he, Rodin, “represented glory while the ambassador merely represented France.”

24

Even so, Monet planned a similar sort of glorification for himself—and both Étienne Clémentel and the Hôtel Biron would become important parts of his plan.

MONET, IN THE

spring and summer of 1916, was an old man in a hurry. “I’m getting old,” he wrote. “I don’t have a moment to waste.”

25

In May he wrote an urgent letter to his supplier of canvases and paints: “I have discovered that I need more canvases, and that I shall need them as quickly as possible.” He ordered six canvases that were to be 2 meters by 1.5 meters (6.5 feet by 4 feet 11 inches) and six more 2 meters by 1.3 meters (6.5 feet by 4 feet 3 inches) in size, “on condition that they be of exactly the same canvas.” Speed was of the essence: he asked for them to be sent “in a sealed crate by the high-speed train to Giverny-Limetz”—though if the packaging and transportation costs should prove excessive, “it would perhaps be best for you to send your automobile again.”

26

Monet’s supplier was a Paris firm called L. Besnard (“Canvases, Fine Colours, Panels”), near Place Pigalle. Monet dealt with an employee in the shop, a certain Madame Barillon. She was presumably accustomed to these frantic requests from Giverny, and there would certainly be more of them to come. Monet’s enthusiasm for his “famous decorations,” as he began calling them, remained intact through the winter and spring as he continued to “work hard” on them.

27

His vision remained good, but other things troubled him, in particular the poor weather—blamed by many, once again, on the heavy bombardment on the western front.

28