Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies (39 page)

Read Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies Online

Authors: Ross King

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Architects, #History, #General, #Modern (Late 19th Century to 1945), #Photographers, #Art, #Artists

A small group gathered in Giverny for the celebrations. Two figures were conspicuous by their absence: Clemenceau, who was in Singapore; and Thiébault-Sisson, who “bothered me so much during his stay in Giverny,” as Monet told Joseph Durand-Ruel, “that I fear I’ve come to pray that he will refrain from coming here on the 14th.”

26

A senator and the new prime minister, Georges Leygues, were likewise dissuaded in

order to keep the occasion intimate and unofficial for a man who disliked crowds and ceremonies.

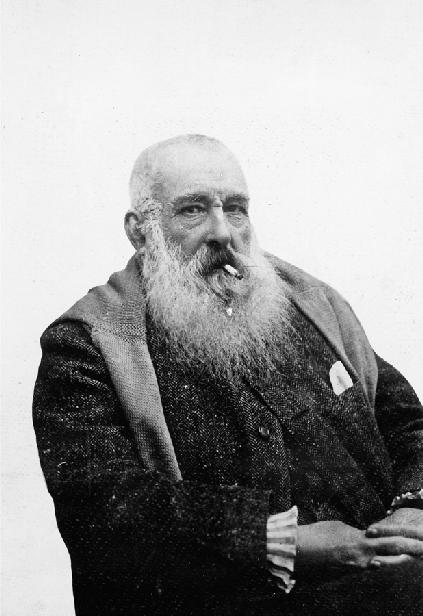

Claude Monet on his eightieth birthday, typically attired in English herringbone tweed

Certain formalities were nonetheless observed. A friend, the duc de Trévise, a descendant of one of Napoleon’s generals and a noted art collector, recited a poem in Monet’s honor. “You paint, what’s more to say?” his poem began—and then ran to some twenty stanzas.

27

A photographer, Pierre Choumoff, was on hand to snap photographs. One of them showed Monet looking relaxed in tweeds and pleated cuffs, a handkerchief peeping out of his breast pocket. Everyone was agreed that the master looked energetic and youthful—sixty rather than eighty. “He provides striking evidence,” wrote Alexandre, “of the inanity of what used to be called the age limit.”

28

Another friend christened him “the old oak of Giverny,” pointing out that, although his beard was white, his dark eyes were “acute and profound” and his body unbowed.

29

To Trévise he had “the appearance of a leader, full of vigour, simplicity and authority,” and his lively, robust physique reminded him of a wrestler—which was appropriate, he noted, since Monet wrestled with his paintings and with nature.

30

Soon after Monet’s eightieth birthday, the socialist newspaper

Le Populaire

carried a mischievous report: “Several members of the Académie des Beaux-Arts have suggested that Claude Monet could take the seat left vacant by the departure for the hereafter of Luc-Olivier Merson. We don’t know the names of these courageous men who would dare to introduce the great painter into the Academy of so-called Fine Arts. But we would love to know who they are.”

31

The official consecration of Monet therefore looked set to continue. The Académie des Beaux-Arts was one of the sections of the Institut de France, the official guardian of French art, science, and literature. Members of the institute, the “Immortals,” wore green coats embroidered with laurels and occupied plush green seats, the famous

fauteuils

, in the domed building on the Left Bank of the Seine. The Académie des Beaux-Arts consisted of forty members, including fourteen painters and eight sculptors. For someone to be admitted into this august company at the age of eighty would have been unprecedented. The average age of

members of the Académie des Beaux-Arts in 1920 was sixty-nine. Only two members were older than Monet: Jean-Paul Laurens at eighty-two and Léon Bonnat at eighty-seven, but both had been elected as much younger men. In 1920, the average age of the members at their election had been fifty-five—an indication of just how overdue the honor was in the case of Monet.

Indeed, this talk of belatedly elevating Monet into the ranks of the Immortals starkly revealed how for many decades both he and the other Impressionists had been deliberately ignored by officialdom. “Claude Monet is 80 years old,”

Le Populaire

pointed out. “To think it took that long for him to be deemed worthy of a place among the illustrious official painters.” But of course the Académie des Beaux-Arts was the staunch defender of conservative artistic values. Merson had been typical, a specialist in the kind of mythological, historical, and religious scenes—complete with dewy-eyed sentiments and valiant, gratuitous nudity—against which the Impressionists had rebelled in the 1860s and 1870s. In 1911 a critic named Émile Bayard, proclaiming

“Haro les impressionnistes!”

(“Down with the Impressionists!”), had celebrated Merson, along with Laurens and Bonnat, as staunch defenders of a “classical tradition” against the encroachments of Impressionism.

32

Bonnat had served on the 1869 Salon jury that rejected Monet’s two offerings,

Fishing Boats at Sea

and

The Magpie

. “He detested my painting,” Monet later explained, “and I never thought much of his.”

33

Bonnat had been a close friend of Jean-Léon Gérôme, the archnemesis of the Impressionists who, famously, had hastily conducted visiting dignitaries away from a room exhibiting Impressionist paintings at the 1900 Exposition Universelle—a room that included fourteen Monets—with the words: “Pass by, gentleman, here we have the disgrace of French art.”

34

Gérôme had, of course, been a stalwart member of the Académie des Beaux-Arts until his death in 1904.

Would Monet wish to become a member of such a club?

Le Populaire

ended its report by noting that if Monet were to refuse their offer, “what a blow to the Institut!” Unlike his friend Manet, who had been eager for medals (“In this bitch of a life,” Manet once claimed, “one can never be too well-armed”),

35

Monet scorned official honors. Jean-Pierre Hoschedé

claimed that he had turned down the Legion of Honor because he regarded such recognition as “a medal for well-behaved children.”

36

Clemenceau was equally contemptuous. Although unani mously elected to another section of the Institut de France, the Académie Française, in November 1918, he once said: “Give me forty assholes and I give you an Académie Française.”

37

Over the next few months, gossip about Monet and the vacant seat in the Académie des Beaux-Arts was sprinkled through the newspapers. “Will the master Claude Monet consent to enter the Institut?” a newspaper breathlessly asked.

38

Despite talk of a seat being “offered” to Monet, membership actually required an election by secret ballot after candidates, approached by sitting members, allowed their names to go forward. There was no shortage of candidates to replace Merson, with

Le Figaro

reporting that six men had been approached. “They then thought—a little tardily—of Claude Monet.”

39

If this report was true, Monet might have been miffed at the fact that he was apparently not one of the first people approached. In any case, he soon made it clear that he had no wish to join the ranks of the Immortals. In December, one of his friends, who went unnamed, told

Le Figaro

: “He was afraid that if he became a member of the Académie, people would ask him why, and he’d prefer people asking him why he was not.” The newspaper then observed: “Such high disdain is sweet revenge for forty years of stupidity and anxious, scrupulous hatred.”

40

Monet may well have enjoyed exacting sweet revenge. However, to snub the artistic establishment, and to risk appearing surly and ungrateful, was hardly politically wise at a time when he needed hundreds of thousands of francs of public money to make his gift to the nation possible. Had Clemenceau not been, as a newspaper reported, “shooting his namesakes in India,” he may have counseled Monet to accept.

41

PLANS FOR THE

oval pavilion did not progress happily. Louis Bonnier made a second trip to Giverny at the end of November 1920, along with Paul Léon and Raymond Koechlin. That evening Bonnier wrote glumly in his diary: “The whole project has to be rethought.”

42

He quickly

produced yet another plan. According to this latest design, the pavilion was to be made from reinforced concrete; it would feature a polygonal exterior and a brick façade painted white in order, as Bonnier wrote, to give an impression of “great simplicity” and “quiet neutrality.” Entered through a wrought-iron door, the interior would be twenty-five meters in diameter, featuring a “distinctive shape...true to the instructions provided by the program of Monsieur Claude Monet.”

43

Illumination was to be obtained by means of a glass ceiling through which a vellum blind would gently diffuse sunlight.

At the end of the year, Bonnier’s plan was submitted for approval to the General Council for Public Buildings. “For the exterior,” Bonnier had emphasized, “we have not sought any effect for the planned building that might be detrimental to the architecture of the Hôtel Biron.”

44

Alas, the architects on the committee did not see things in the same light, unanimously turning down the design, which they found too modern in comparison with the stately grace of the eighteenth-century Hôtel Biron, in whose grounds it was to sit. The rejection of Bonnier’s modernist pavilion was not, perhaps, surprising, given both the historic location and the artistic temperament of the time, embodied in recent legislation to do with rebuilding after the war. This new law stipulated that architects should “ensure, to the greatest extent possible, the preservation of historical and archaeological memories, maintaining the special architectural style of the region and a respect for landscapes, sites and scenic aspects, which are an important part of the artistic heritage and morale of our people.”

45

Bonnier hastily assured Monet that the General Council’s decision could be overturned, but Monet disliked the plan in any case. His unhappiness stemmed from the fact that the “distinctive shape” designed by Bonnier was not elliptical but, for reasons of cost, circular. “I confess to be a little disappointed in the way the room, with its regular shape, looks like it’s been designed for a circus,” he wrote cuttingly to Paul Léon. “I fear such a shape will not produce a good effect.” He then told Léon that to reduce costs he was willing to accept a smaller building so long as it was elliptical—but this reduction in space meant, regrettably, that his

donation would shrink accordingly, from a dozen panels to only eight or ten.

46

To Camille Pissarro’s son Lucien he bitterly complained that the donation had become more trouble than it was worth.

47

There was, at least, progress with

Women in the Garden

. In early February 1921 he was able to report that the painting was “en route to Paris.”

48

The massive canvas had been removed from the wall and carried down the stairs, where Monet carefully superintended its placement in the truck sent by Paul Léon. He confessed that the departure of the painting was heartbreaking because of “the many memories it holds for me.”

49

He had painted the work in the year he had met nineteen-year-old Camille Doncieux, who posed for three of the figures, most spectacularly as the young woman of fashion seated in the grass in a voluminous Worth dress, a bouquet of flowers on her lap. For many decades, young, pale, and beautiful, shaded by her parasol from the light of a long-ago sun, she had gazed sightlessly down on the life at Giverny that she had never known.

IF SISTER THÉONESTE

was the only person in France who could manage Clemenceau, then Clemenceau was the only person in France who could manage Monet. Heavy sighs of relief must therefore have been heaved in Paul Léon’s office when, on March 21, 1921, the Tiger returned from his six-month expedition to the Far East. As Léon later recalled: “Monet, aged, anxious and menaced with blindness, was prey to fits of discouragement. Each day we had to stop him putting his foot through his paintings. He constantly changed plans and dimensions, putting us in an awkward situation. It was often necessary to appeal to Clemenceau for arbitration.”

50

Clemenceau’s tour had been wildly successful. “He went everywhere, saw everything, and talked to everybody,” wrote Sir Laurence Guillemard, the governor of the Straits Settlements, on the Malay Peninsula. “The charm of his manner was irresistible; his gay humour was infectious; his courtesy won all hearts, and in two days he was the idol of Singapore. He never seemed tired. Every morning he came down to breakfast in high spirits.”

51

At the invitation of the sultan of Johor

he went on a tiger-hunting expedition but returned empty-handed from the humid jungle. He had better luck when he moved on to India and, wearing a pith helmet, a bow tie, and his ubiquitous gray gloves, set off on a three-day hunt with the maharajah of Gwalior, with whom he bagged several specimens. He also enjoyed less predatory delights, writing to Monet from Varanasi in Uttar Pradesh: “Let it not be said that I came to Bénarès [Varanasi] to enjoy the most prodigious bath of light and that I did not find a word to say to the man called Claude Monet.” Just as he had described the beauty of sunlight of the Nile, so, too, he sent a description of the Ganges, “a great, clear river with a grand sweep of white palaces that fade in the powdery light of dawn. In the splendour of their clarity and simplicity the river and sky enfold the whole life of things. If I were Claude Monet I should not wish to die without seeing it.”

52

Monet had taught Clemenceau a sensitivity to the special quality of the effects of light, especially over water. As he would later write to Monet: “I love you because of who you are, and because you taught me to see light. In this way you’ve enriched my life.”

53