Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies (38 page)

Read Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies Online

Authors: Ross King

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Architects, #History, #General, #Modern (Late 19th Century to 1945), #Photographers, #Art, #Artists

Plans for the donation had therefore been finalized at last. The gift had swollen from a pair of paintings to a dozen, complete with a purpose-built venue, to be constructed according to Monet’s specifications in the grounds of the Hôtel Biron, which for the past year had housed the museum devoted to the work of Rodin. It is not clear when

the Hôtel Biron was decided as an appropriate location or who first suggested it, but Monet had no doubt been contemplating such a site for himself ever since Rodin first signed the papers for his own donation in 1916. France’s greatest sculptor and her greatest painter—the two men whose glorious paths through the artistic firmament had followed such similar trajectories—would therefore come together in a single, magnificent space: the Musée Rodin side by side with a Musée Monet.

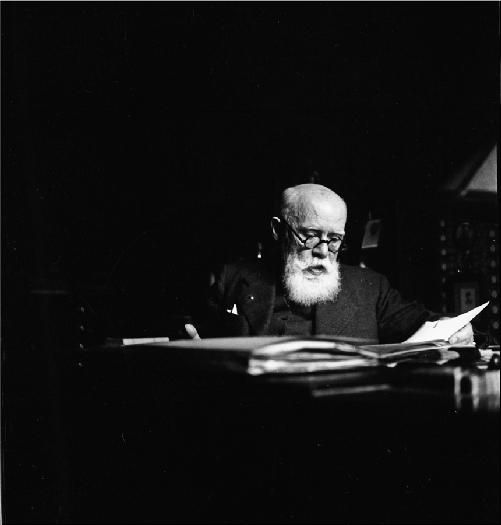

One day after this momentous lunch at Giverny, an architect named Louis Bonnier, at his home in the rue de Liège, near the Gare Saint-Lazare, took a telephone call from Paul Léon. The sixty-four-year-old Bonnier was, like Léon, a busy and important man. He was architect in chief of civil buildings and national palaces, surveyor in chief of the city of Paris, and director of architectural services for the prefect of the Seine. Bald and with a white ruff of beard, he was an arbiter of architectural tastes and the author of numerous municipal reports on public hygiene, urban renewal, and cultural heritage. He had been the force behind a new set of building regulations—allowing for greater height and variety—that made possible the construction of some of Paris’s most stylish Art Nouveau buildings. “The people have as much right to beauty,” he once famously declared, “as they do to hygiene.”

5

Bonnier was, besides, a practicing architect of no little distinction. He had built the town hall at Issy-les-Moulineaux as well as various elegant villas, including one in Auteuil for the writer André Gide. His only defect, according to a newspaper, was the unfortunate one shared by all architects, namely that “when they build a monument, they do not care in the slightest degree about the people for whom the building is done.”

6

Gide would have agreed: his house in Auteuil, though grand and emphatically à la mode, was ruinously expensive, poorly lit, and so cold that in winter he took to swaddling himself in multiple pullovers and wearing a woollen hat and mittens.

7

Bonnier had another notable building to his credit. Almost a quarter of a century earlier he had been the consulting architect on Claude Monet’s light-filled second studio at Giverny. He had come to know Monet thanks to his wife, Isabelle, whose brother, the landscapist

Ferdinand Deconchy, was an old friend of Monet’s who lived in the village of Gasny, only four miles from Giverny. Monet had expressly asked for Bonnier to serve as architect on the Hôtel Biron project, not only because they knew one another, but also, no doubt, because of Bonnier’s eminent reputation and his connections at the highest levels of government. Bonnier accepted the job and immediately made plans to visit Giverny to discuss matters with his client.

Monet’s beleaguered architect Louis Bonnier

Bonnier arrived in Giverny in early October accompanied by Ferdinand Deconchy. He listened carefully to Monet’s instructions, studied his canvases, took their measurements, and afterward, back at his office, made an ominous memo: “Foresee great expense for the pavilion.”

8

Ordinarily Bonnier did not trouble himself with such trifling matters as the cost of a project. The cost overruns on the house in Auteuil had driven Gide to despair: “I scarcely know how I shall pay for it—or how, after paying for it, we shall live.”

9

But the cost of Monet’s pavilion

did concern Bonnier, mainly because the project needed governmental approval. “The State would be very embarrassed to refuse a gift that could cost it a million francs,” he wrote.

10

In particular, Monet’s specifications were problematic. Monet was adamant that the pavilion should be built to his own instructions, and his main instruction was that it should be oval in shape—a design that would, he believed, allow for the best display of his twelve canvases. However, Bonnier calculated that the construction of an elliptical room, with its elongated axis and variable curvature, would cost 790,000 francs, a sum that he feared would struggle to gain government approval. On the other hand a circular room, which he advised instead, would only cost 626,000 francs.

11

When Monet remained inflexible, Bonnier duly set to work designing an oval shape, sending the first rough plan to his client within two days of their meeting. However, Monet was not happy and suggested certain revisions. “Monet has a new idea each day,” Bonnier lamented.

12

And so was to begin yet another unspeakable drama: that of the pavilion.

MONET’S DONATION WAS

at last something much more substantial than a vague promise made in the aftermath of the armistice. As Louis Bonnier toiled late into the night on his various plans for the pavilion, word of the project reached the ears of the press.

THE PAINTER CLAUDE MONET DONATES TWELVE OF HIS FINEST CANVASES TO THE STATE

, declared a headline in

Le Petit Parisien

in the middle of October.

13

Another newspaper reported, with no undue awe, the sheer scale of this gift to the nation: 163 meters (178 yards) of painting.

14

This figure was an exaggeration, and Monet wrote to the author to correct him, good-humoredly pointing out that such an expanse “would have been too cumbersome for the State.”

15

However, in its totality the Grande Décoration would actually encompass this prodigious swath and then some. In December he would report that his Grande Décoration consisted of forty-five to fifty panels making up fourteen separate series. All of these panels, he claimed, measured 4.25 meters wide by 2 meters high (14 feet by 6.5 feet) except for three that had been done on single canvases measuring 2 meters high by 6 meters (almost 20 feet) wide.

16

The

Grande Décoration at the time of this accounting therefore stretched for more than 200 meters. Barely a quarter of these canvases formed the donation to the state arranged in 1920.

In fact, Monet’s twelve panels consisted of 51 meters (56 yards) of canvas, covering a total area of just over a 100 meters. François Thiébault-Sisson wrote his own more accurate account of the donation in

Le Temps

, describing how the canvases would be arranged end to end along the walls of the new glass-ceilinged pavilion.

17

His article allowed readers to envisage the display: a dozen panels, each 2 meters by 4.25 meters (6.5 feet by 14 feet), arranged around an elliptical room to form four separate large-scale compositions separated by narrow breaks and giving the impression of one continuous scene. The dozen canvases would form four compositions:

Green Reflections

(made up of two panels),

The Clouds

(three panels),

Agapanthus

(three panels), and

The Three Willows

, a work that encompassed four panels and therefore stretched to 17 meters (almost 56 feet) in length.

But that was not all. Thiébault-Sisson reported that the skylight in the pavilion would be high enough to allow Monet to “introduce decorative motifs” at intervals in the spaces above the dozen canvases. He was planning, in fact, a series of panels showing the wisteria festooning his Japanese bridge. He would ultimately produce nine of these “garlands,” as he called them.

18

Since these panels ranged between 2 and 3 meters across, he was adding some 20 more meters (more than 60 feet) of canvas to his donation.

The munificence of the donation, with these vast reaches of canvas, appears to have made Monet regard any fuss about the project’s funding as petty and ungrateful. Thiébault-Sisson noted that Monet’s gift was especially generous given that in the last six months he had received offers to purchase “all or part of this work”—an allusion to the overtures of Zoubaloff and Ryerson. Thiébault-Sisson was careful to imply that the door had not been definitively closed on these would-be patrons and that one of them came from faraway Chicago. “All these offers,” he pointedly declared, “flattering as they were, have been provisionally declined.”

19

A sale to Ryerson was a convenient threat to use

against those who might object to the tremendous expense to the state of the donation—those who, like the journalist for the socialist weekly

Le Populaire

, complained: “Will the Chamber of Deputies really grant funds for the construction of a pavilion for the installation of the paintings donated by Claude Monet to the State? Does the donation really require a new building?”

20

The many debates around Rodin’s donation could have left Monet and his allies in no doubt about the upcoming fights on the floor of the chamber and in the pages of the newspapers. Ryerson’s offer to whisk the paintings away to Chicago—an offer that had only been “provisionally declined”—would therefore be an important bargaining chip. Further pressure was exerted by a journalist for

L’Humanité

, a onetime newspaper colleague of Clemenceau’s named François Crucy, who argued that Monet was a prophet without honor in his own land. He noted that for the past thirty years Monet’s work had been celebrated in America, Britain, and Germany, that his paintings were well represented in foreign museums, but that French museums, by contrast, possessed only a few scattered canvases. Such “prolonged negligence,” he wrote, made for an obligation to support Monet’s donation, which was all the more valuable given the institutional neglect of his work.

21

The critic Arsène Alexandre, writing in

Le Figaro

, took another tack, praising the quality of the paintings and anticipating the incomparable splendor of the display. Few of his readers could have objected to the cost, so lip-smacking was his description of this new series of paintings—not one of which, of course, had ever been put on public display. These latest paintings, Alexandre declared, showed not only the continued strength of Monet’s pictorial power “but also a new breadth of vision, an abundance of lyricism that both summarizes and goes beyond anything we knew of him.” He wrote that the exhibition of Monet’s enormous paintings in a specially adapted oval room of the “Musée Monet” would be “a feast for the eyes that is unprecedented in any school and in any age.” The visitor to this unique museum would be “plunged into the passion of color and the hundredfold dream of the great artist.” Striking a patriotic note, he wrote that the paintings “will go all around

the world to sing, in their suave and intoxicating harmonies of color, the inexhaustible richness of French art.”

22

Alexandre had one further announcement for readers of

Le Figaro

: “The State, wishing to recognize Monet’s generosity, has acquired for our museums an excellent work of his youth,

Women in the Garden

, a painting from the epoch of Manet that was refused at the 1867 Salon.” This painting would be placed in the Luxembourg Museum, where it would join Manet’s

Olympia

, “a work of equivalent importance and signification.” Alexandre did not give the price paid for this painting of Monet’s youth, but another newspaper soon provided details: “The purchase price, which would have terrified the jury of 1867, as well as the public, is, today, relatively modest: 200,000 francs.”

23

There was, in fact, nothing modest about this price, even for such a large work, especially since Monet had noted that the going rate for one of his paintings was 25,000 francs.

Hearing the amount that Monet was to receive for this work, René Gimpel exclaimed: “Monet is a true Norman!”

24

The most common synonyms for Norman were

malin

(shrewd, cunning),

futé

(crafty), and

roublard

(wily).

25

It was indeed a wily maneuver. In reaping such a large sum for a work once derided by officialdom, Monet had extracted a brutal, satisfying, and lucrative revenge on history.

IN THE MIDDLE

of November, a further cause for celebration presented itself. “Today,” declared an article on the front page of

Le Figaro

on November 14, “the illustrious founder and lone survivor of ‘Impressionism’ reaches the age of eighty. Still active in his studios in Giverny, he receives only on Sunday. His friends take the opportunity to bring him their good wishes in private.”