Mandarins

Authors: Ryunosuke Akutagawa

MANDARINS

Stories by

Ry

Å«

nosuke Akutagawa

Translated from the Japanese by Charles De Wolf

archipelago books

English translation and notes © 2007 Charles DeWolf

First Archipelago Books edition 2007

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced

or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior

written permission of the publisher.

Archipelago Books

232 Third Street, #

AIII

Brooklyn, NY 11215

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Akutagawa, Ry

Å«

nosuke, 1892â1927.

Mandarins : stories / by Ry

Å«

nosuke Akutagawa ; translated from the

Japanese by Charles De Wolf.

p. Â cm.

ISBN

978-0-9778576-0-9 (alk. paper)

1. Akutagawa, Ry

Å«

nosuke, 1892â1927 â Translations into English.

I. De Wolf, Charles. II. Title.

PL

801.

K

8

A

6 2007

895.6'342âdc22 Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 2007015994

Distributed by Consortium Book Sales and Distribution

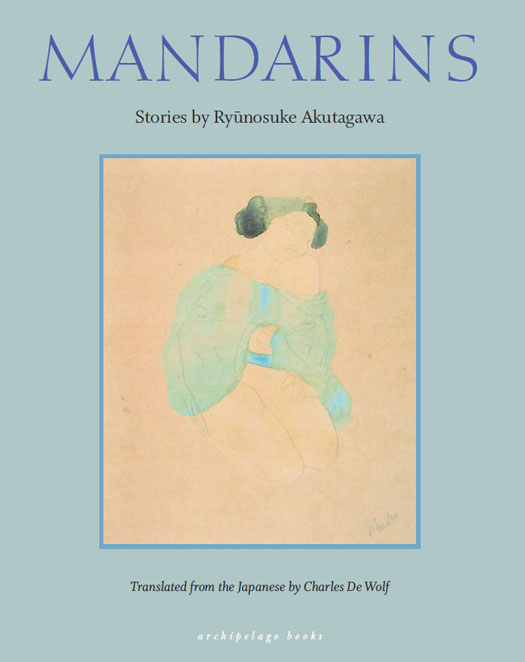

Cover art:

Reclining Nude

, by Auguste Rodin 1919,

Mus

é

e Rodin, Paris.

This publication was made possible with support from Lannan

Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the New

York State Council on the Arts, a state agency.

CONTENTS

MANDARINS

Evening was falling one cloud-covered winter's day as I boarded a T

Å

ky

Å

-bound train departing from Yokosuka. I found a seat in the corner of a second-class coach, sat down, and waited absentmindedly for the whistle. Oddly enough, I was the only passenger in the carriage, which even at that hour was already illuminated. Looking out through the window at the darkening platform, I could see that it too was strangely deserted, with not even well-wishers remaining. There was only a caged puppy, emitting every few moments a lonely whimper.

It was a scene that eerily matched my own mood. Like the looming snow clouds, an unspeakable fatigue and ennui lay heavily upon my mind. I sat with my hands deep in the pockets of my overcoat, too weary even to pull out the evening newspaper.

At length the whistle blew. Ever so slightly, my feeling of gloom was lifted, and I leaned my head back against the window frame,

half-consciously watching for the station to recede slowly into the distance. But then I heard the clattering of dry-weather clogs coming from the ticket gate, followed immediately by the cursing of the conductor. The door of the second-class carriage was flung open, and a young teenage girl came bursting in.

At that moment, with a shudder, the train began to lumber slowly forward. The platform pillars, passing one by one, the water carts, as if left carelessly behind, a red-capped porter, calling out his thanks to someone aboardâall this, as though with wistful hesitancy, now fell through the soot that pressed against the windows and was gone.

Finally feeling at ease, I put a match to a cigarette and raised my languid eyes to look for the first time at the girl seated on the opposite side. She wore her lusterless hair in ginkgo-leaf style. Apparently from constant rubbing of her nose and mouth with the back of her hand, her cheeks were chapped and unpleasantly red. She was the epitome of a country girl.

A grimy woolen scarf of yellowish green hung loosely down to her knees, on which she held a large bundle wrapped in cloth. In those same chilblained hands she clutched for dear life a red third-class ticket.

I found her vulgar features quite displeasing and was further repelled by her dirty clothes. Adding to my irritation was the thought that the girl was too dimwitted to know the difference between second- and third-class tickets. If only to blot her existence from my mind, I took out my newspaper, unfolded it over my lap, and began to read, still smoking my cigarette.

All at once the light from outside was eclipsed by the electric illumination within; now the badly printed letters in some column or other stood out with a strange clarity. We had entered one of the Yokosuka Line's many tunnels.

Yet the better lighting for my perusal of the pages was of no help in distracting me from my melancholy; instead I was only weighed down all the more by the myriad commonplace matters of the world: peace treaty issues, weddings, some sort of bribery scandal, death notices. For a moment after the train entered the tunnel, I had the illusion that we had somehow reversed direction, as my eyes moved almost mechanically from one tiresome article to another. At the same time, I was, despite myself, rather conscious of the girl sitting in front of me, as though she were the personification of coarse reality.

The train in the tunnel, this country girl, this newspaper laden with triviaâif they were not the very symbols of this unfathomable, ignoble, and tedious life of ours, what were they?

In disgust, I tossed aside the paper I had hardly read and again leaned my head against the window frame. My eyes closing as though I were dead, I began to doze.

Minutes later, I was startled from my half slumber and instinctively looked about me with a feeling of alarm. At some point the girl had come over to my side of the train and was now next to me, feverishly endeavoring to open the window, the glass apparently proving to be too heavy for her. At intervals, I could hear her sniffling and gasping, her chapped cheeks redder than ever.

All of this should have been enough to evoke some measure of sympathy, even in the likes of me. Yet surely she could have seen that the hillsides, their dry grass alone illuminated in the twilight, were moving inexorably closer toward the glass panesâand known that at any moment we would again be in darkness. Still, quite incomprehensibly to me, she continued her attempt to lower the closed window. I could only imagine it as sheer caprice and so inwardly nurtured my original malice. Gazing coldly at her desperate struggle as she fought with chilblained hands, I hoped that she would be forever doomed to fail.

Then, with an enormous groan, the train plunged into a tunnel, and at that very moment the window at last came down with a thud. A stream of soot-laden air came pouring in through the square opening. Instantly, the carriage was filled with a cloud of suffocating smoke. Already suffering from an impaired throat, I had not even the time to put a handkerchief to my face and was now coughing so violently that I could scarcely catch my breath. Yet the girl, without the slightest pretense of concern for my plight, had poked her head out of the window and was staring relentlessly ahead, her side-locks disheveled by the breeze sweeping through the darkness. When at last my cough had eased, I peered at the figure through the smoke-dimmed light and would surely have barked at this strange creature to shut the window, had it not been for the outside view, which now was growing ever brighter, and for the smell, borne in on the cold air, of earth, dry grass, and water.

Already the train was gently gliding out of the tunnel and approaching a crossing at an impoverished

banlieue

surrounded by withered hills. Near the road lay clumps of thatch- and tile-roofed houses, each shabbier than the next. Fluttering in the dying light of the day was a white flag, perhaps being waved by a flagman.

Finally!

I thought to myself, and just then saw standing behind the barrier of that desolate crossing three red-cheeked boys pressed up against one another, so small of stature that they seemed to have been crushed under the weight of the oppressive sky, the color of their clothing as drab as these urban outskirts. Looking up to see the train as it passed, they raised their hands as one and let out with all the strength of their young voices a high-pitched cheer, its meaning quite escaping me. And at that instant the girl, the full upper half of her body leaning out the window, abruptly extended her ulcerated hands and began swinging them briskly back and forth. Five or six mandarin oranges, radiating

the color of the warm sun and filling my heart with sudden joy, descended on the children standing there to greet the passing train.

Quite involuntarily, I held my breath and knew immediately the meaning of it all. This girl, perhaps leaving home now to go into service as a maid or an apprentice, had been carrying in her bosom these oranges and tossed them to her younger brothers as a token of gratitude for coming to the crossing to see her off.

Everything I had seen beyond the windowâthe railway crossing bathed in evening light, the chirping voices of the children, and the dazzling color of the oranges raining down on themâhad passed in a twinkling of an eye. Yet the scene had been vividly and poignantly burned into my mind, and from this, welling up within me, came a strangely bright and buoyant feeling.

Elated, I raised my head and gazed at the girl with very different eyes. Without my noticing when, she had resumed her place in front of me, her chapped cheeks buried as before in her woolen scarf of yellow-green. Again she held a large bundle on her lap, her hand still clutching a third-class ticket . . . And now for the first time I was able to forget, at least for a moment, my unspeakable fatigue, my ennui, and, with that, this unfathomable, ignoble, and tedious life.

1

. . . It went on raining. We finished lunch and began talking about our friends in T

Å

ky

Å

, turning many a Shikishima cigarette to ashes.