Manhunt: The Ten-Year Search for Bin Laden--From 9/11 to Abbottabad (19 page)

Read Manhunt: The Ten-Year Search for Bin Laden--From 9/11 to Abbottabad Online

Authors: Peter L. Bergen

Tags: #Intelligence & Espionage, #Political Freedom & Security, #21st Century, #United States, #Political Science, #Terrorism, #History

When Zarqawi was killed in an American air strike six months later, bin Laden’s subsequent public statements of admiration for him were only because Zarqawi had taken the fight to the Americans in Iraq in a manner that bin Laden himself could only dream of. Privately, bin Laden was worried that Zarqawi had grievously

harmed the al-Qaeda brand, and in October 2007, al-Qaeda’s leader even issued an unprecedented public apology for the behavior of his followers in Iraq,

scolding them for “fanaticism.”

As bin Laden’s stay in Abbottabad lengthened into years, his central focus always remained attacking the United States. By early 2011 he was keenly aware that almost a decade had passed since a successful attack on America. As the tenth anniversary of his great victory against the Americans approached, bin Laden wrote messages to al-Qaeda’s franchises in Algeria, Iraq, and Yemen reminding them that

America was still their main enemy, and admonishing

them not to be distracted by local fights. He schemed about assassinating President Obama and General David Petraeus, who had inflicted such heavy losses on al-Qaeda’s affiliate in Iraq, although he observed that killing Vice President Joe Biden would likely be a waste of time because he was

not a sufficiently important target. To his team, bin Laden emphasized the continued importance of targeting major American cities such as Chicago, Washington, New York, and Los Angeles. Rahman frequently had to remind bin Laden that

al-Qaeda simply didn’t have the resources to carry out his ambitious plans. Some of bin Laden’s other lieutenants pointed out to him that it would be much more realistic to focus on fighting American soldiers in Afghanistan rather than trying to

attack the United States itself, advice bin Laden simply ignored.

Writing in his journal, bin Laden, a meticulous note taker, tallied up

how many thousands of dead Americans it would take for the United States to withdraw finally from the Arab world.

He mused about attacking trains by putting trees or cement blocks on railroad tracks in the United States, and he suggested that al-Qaeda enlist non-Muslim American citizens opposed to their own government, citing

disaffected African Americans and Latinos as potential recruits. Al-Qaeda enjoyed only modest success with this tactic, recruiting

Bryant Neal Vinas, an unemployed Hispanic American from Long Island, who participated in an attack on a U.S. base in Afghanistan in 2008 before he was arrested by the Pakistanis and handed over to American custody.

Bin Laden exhorted his followers to plan an attack on the United States to coincide with the

tenth anniversary of 9/11 or with holidays such as

Christmas, and he advocated attacks on

oil tankers as part of a wider strategy to bleed the United States economically. He ordered Rahman also to focus on recruiting jihadists for attacks in Europe. Al-Qaeda’s last successful European attacks had been the

four suicide bombings on London’s transportation system on July 7, 2005, which killed fifty-two commuters. Rahman was

in touch with a group of Moroccan militants living in Düsseldorf, and

in the fall of 2010, al-Qaeda’s leaders were impatient to pull off an attack with multiple gunmen somewhere in Germany, though this plan fizzled out.

In one of his more blue-sky moments, bin Laden considered changing the name of al-Qaeda, which he believed had developed something of a branding problem. He worried that the full name of the group, al-Qaeda al-Jihad, which means “The Base for Holy War,” was being lost in the West, where the group was known, of course, simply as al-Qaeda. Bin Laden believed that lopping off the word

jihad

had allowed the West to “claim deceptively that they are not at war with Islam.” Bin Laden mulled over some decidedly un-catchy alternative names: the

Monotheism and Jihad Group and the Restoration of the Caliphate Group.

Bin Laden paid a great deal of attention to his relatively new but quite promising Yemen-based affiliate, al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula. It was this affiliate that had managed to smuggle a bomb onto an American passenger jet in the underwear of Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, the Nigerian recruit who tried, unsuccessfully, to detonate the device as the plane flew over Detroit on Christmas Day 2009. Bin Laden gave tactical advice to the group, which published

Inspire

, an English-language webzine aimed at recruiting militants in the West. In one issue of

Inspire

a writer proposed that jihadists turn a tractor into a weapon by outfitting it with giant blades and then driving it into a crowd. Bin Laden tut-tutted that such indiscriminate slaughter

did not reflect al-Qaeda’s “values.” And bin Laden made important personnel decisions for the group. When the leader of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula suggested appointing the American-born cleric Anwar al-Awlaki to head the

organization, because his name recognition in the West would help with fund-raising, bin Laden nixed the idea, saying that he

didn’t know Awlaki and was quite comfortable with the leadership already in place.

Bin Laden also offered strategic advice to his Yemeni followers, warning that there wasn’t yet enough “steel” in al-Qaeda’s support in the region to try to impose a Taliban-style regime there.

His key lieutenants wrote to bin Laden about the problems they were facing; chief among them was the campaign of American drone strikes in Pakistan’s tribal regions. The U.S. drone campaign had begun there in 2004, under President Bush, but, as we have seen, President Obama had massively expanded the program. Under Bush, there had been one strike every forty days; under Obama, the tempo increased to one every four days. The strikes had made the position of al-Qaeda’s “number three” one of the world’s most perilous. In May 2010, down a dirt road from Miran Shah, the main town in the tribal region of North Waziristan, a missile from a drone killed Mustafa Abu al-Yazid, along with his wife and several of their children. Yazid was a founding member of al-Qaeda who served as the group’s number three and oversaw the group’s plots, recruitment, fund-raising, and internal security. In the past two years, bin Laden had also lost to drone strikes his chemical weapons expert, his chief of operations in Pakistan, his propaganda chief, and

half a dozen other key lieutenants.

Rahman wrote to bin Laden that al-Qaeda was

getting hammered by the drones, and asked whether there were alternative locations where the organization might rebase itself. Bin Laden instead approved the formation of a

counterintelligence unit to root out the spies in the tribal areas who were providing pinpoint-accurate information to the Americans about the locations of his lieutenants. In 2010, however, he received a complaint that the counterintelligence shop could barely function on its small budget of a few thousand

dollars. A particular worry for both bin Laden and Rahman was the fact that cash flow at al-Qaeda headquarters had by then slowed to a trickle. They corresponded about ways to refill the group’s depleted coffers, focusing in particular on kidnapping diplomats in Pakistan.

Conscious of the pressures that al-Qaeda was now under—its dire financial situation, its decimated leadership bench, and its longtime inability to carry out any attack in the West—bin Laden started casting about for ways to reinvigorate his group. In the spring of 2011 he contemplated a new effort to

negotiate a grand alliance of the various militant groups fighting in Afghanistan and Pakistan. In exchanges with his aides, he also

considered brokering some sort of deal with the Pakistani government: al-Qaeda would halt its attacks in Pakistan and would in turn receive official Pakistani protection. There’s no evidence that this deal ever happened, and it was, in any event, quite a naïve idea. No Pakistani government would make a peace deal with al-Qaeda; bin Laden and his top deputies had for many years publicly and repeatedly called for attacks on Pakistani officials and, as noted ealier, had on two occasions

in 2003 tried to assassinate Pakistan’s president, General Pervez Musharraf.

To the world, of course, bin Laden tried to present a very different image from that of the aging leader of a troubled terrorist group that he had become. Bin Laden once told the Taliban leader Mullah Omar that up to 90 percent of

his battle was fought in the media. Indeed, he took his media campaign seriously, and in the videotapes he shot in a makeshift studio in the Abbottabad compound he dyed his whitening beard jet black and dressed in his finest beige robes trimmed with gold thread. In these videos, he sometimes sat behind a desk and no longer had the gun that had invariably been beside him, a prominent feature of many of his earlier videotaped appearances.

In 2007, bin Laden released a half-hour videotape that received

considerable attention in the West because it was the first time he had appeared on video in three years. On the tape, he spoke directly to the American people from behind a desk in a jihadist parody of a presidential address from the Oval Office. He made no explicit threat of violence but instead urged Americans to convert to Islam and, in a meandering indictment of the United States, invoked the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki; the extermination of Native Americans; the baleful influence of U.S. corporations; and America’s poor record on climate change, as demonstrated by its failure to sign the

Kyoto agreement on global warming. These seemed more the musings of an elderly reader of

The Nation

than the leader of global jihad.

Bin Laden also recorded an average of

five audiotapes a year from his Abbottabad lair, which were passed by courier to As Sahab, al-Qaeda’s propaganda arm. As Sahab would dress up the audio files with photos of bin Laden, graphics, and sometimes subtitled translations and then upload the results to jihadist websites or deliver them to Al Jazeera. On the audiotapes, bin Laden, ever the news junkie, would comment on events both large and small in the Muslim world. In March 2008 he denounced the publication five years earlier of cartoons of the Prophet Mohammed by a Danish newspaper as a “

catastrophe.” Three months later, an al-Qaeda suicide attacker

bombed the Danish embassy in Islamabad, killing six. After a nine-month silence, bin Laden released an audiotape in March 2009 condemning the

recent Israeli invasion of Gaza. In late 2010 he

weighed in on France’s decision to ban Muslim women from wearing the all-enveloping burqa in public, and threatened revenge. Around the same time, he released a tape lambasting the Pakistani government’s slow response to the massive flooding that had displaced twenty million Pakistanis during the summer of 2010.

Bin Laden’s eloquence on every issue of interest to the Muslim

world made his public silence about the events of the Arab Spring of 2011 all the more puzzling. After all, here was what he had long dreamed of: the overthrow of the tyrannical regimes of the Middle East. His silence on the issue is likely explained by the fact that his foot soldiers and his ideas were notably absent in the revolutions that roiled the Middle East. No protestors held aloft pictures of bin Laden or spouted his virulent anti-American rhetoric, and few were demanding Taliban-style theocracies, bin Laden’s preferred political end state. The protests also undercut two of bin Laden’s key claims: that only violence could bring change to the Middle East, and that only by attacking America could the Arab regimes be overthrown. The protestors in Tunisia and Egypt who overthrew their dictators were largely peaceful and were not inspired by al-Qaeda’s attacks on the West; rather, they were ordinary Tunisians and Egyptians fed up with the incompetence and cruelty of their rulers.

How to respond to all this must have been confounding for bin Laden, whose love for the limelight was intense and whose total irrelevance to the most important development in the Middle East since the collapse of the Ottoman Empire was painfully obvious. In late April 2011 he taped an audio message, which was not released before he was killed, in which he welcomed the Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions, saying, “

We watch this great historic event and we share with you joy and happiness and delight.” On the tape, bin Laden said that Sharia law should govern the new Egypt and Tunisia, but strangely did not mention the revolts that were then also spreading in Bahrain, Libya, Syria, and Yemen.

Bin Laden was still revered by his family and followers living on the Abbottabad compound, but by the spring of 2011, as he embarked on his sixth year of residing there, he had become increasingly irrelevant to the Muslim world. The religious Robin Hood image he had projected in the years immediately after 9/11 had largely evaporated,

and most Muslims had rejected al-Qaeda because of its long track record of killing Islamic civilians. Perhaps most fatal to his ambitions, bin Laden never had anything to offer in the way of real solutions to the economic and political problems that continued to plague the Arab world.

Bin Laden at his one and only press conference, held in 1998, in which he declared war against the U.S.

CNN VIA GETTY IMAGES

Doting father Osama bin Laden with son Hamza on January 1, 2001.

HAMID MIR/DAILY DAWN/GAMMA-RAPHO VIA GETTY IMAGES

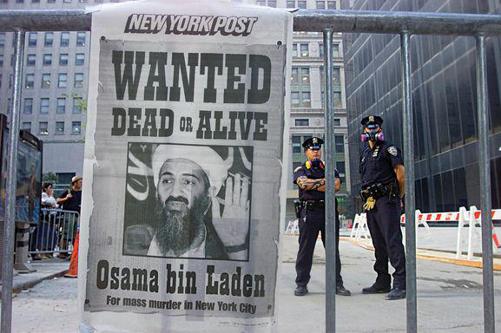

New York police stand near a wanted poster for bin Laden in the financial district of New York on September 18, 2001.

JEFF HAYNES/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

A cave in Tora Bora where al-Qaeda militants sheltered during the Battle of Tora Bora in December 2001.

REZA/GETTY IMAGES

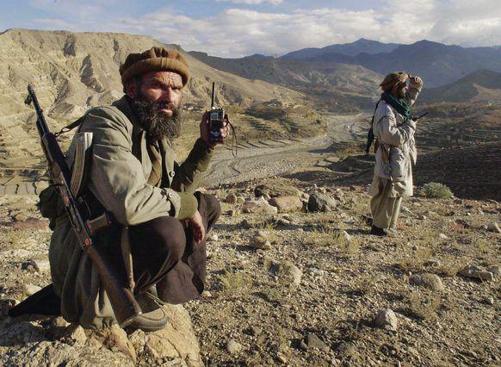

Two Afghan anti-Taliban fighters in Tora Bora on December 6, 2001, as the battle against al-Qaeda reached its height.

ROMEO GACAD/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

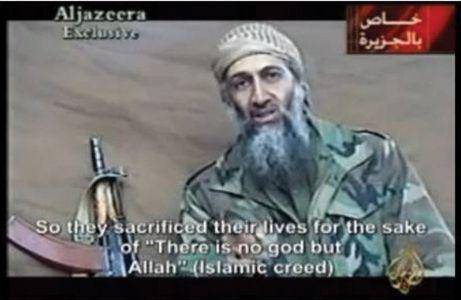

In December 2001, in his first video statement since the 9/11 attacks, bin Laden delivered a message to the American people.

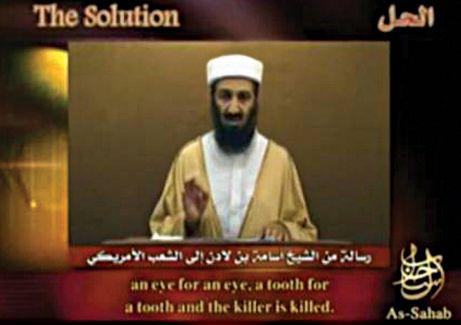

In this video, shot six years later in 2007, bin Laden’s beard has been trimmed and dyed.

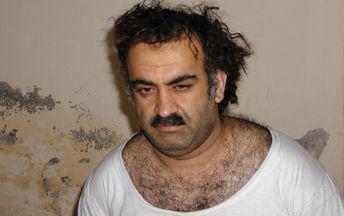

Mohammed al-Qahtani, originally recruited to be a muscle hijacker on 9/11 (top), and Khalid Sheikh Mohammad, the mastermind of the 9/11 attacks (bottom), were captured in 2001 and 2003 respectively. Coercive interrogations of the men yielded contradictory information about “the Kuwaiti,” bin Laden’s courier.

DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE/MCT VIA GETTY IMAGES [AL-QAHTANI]; ASSOCIATED PRESS [KSM]

Between 2003 and 2008, Major General Stanley McChrystal transformed Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) into a commando force of unprecedented agility and lethality, paving the way for Operation Neptune Spear.

PAULA BRONSTEIN/GETTY IMAGES

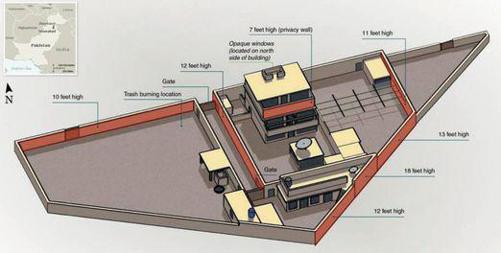

CIA graphic of bin Laden compound in Abbottabad.

CIA

A satellite image of the bin Laden compound in Abbottabad.

DIGITALGLOBE VIA GETTY IMAGES