Manhunt: The Ten-Year Search for Bin Laden--From 9/11 to Abbottabad (20 page)

Read Manhunt: The Ten-Year Search for Bin Laden--From 9/11 to Abbottabad Online

Authors: Peter L. Bergen

Tags: #Intelligence & Espionage, #Political Freedom & Security, #21st Century, #United States, #Political Science, #Terrorism, #History

General James “Hoss” Cartwright (right) laughs with CIA director Leon Panetta.

ALEX WONG/GETTY IMAGES

Undersecretary of Defense for Policy Michele Flournoy testifies before members of Congress alongside Admiral Mike Mullen, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

ALEX WONG/GETTY IMAGES

President Barack Obama shakes hands with Admiral Mike Mullen in the Green Room of the White House, following his statement detailing the mission against bin Laden on May 1, 2011.

OFFICIAL WHITE HOUSE PHOTO BY PETE SOUZA

The architect of the raid on bin Laden’s Abbottabad compound, Vice Admiral William McRaven.

WIN MCNAMEE/GETTY IMAGES

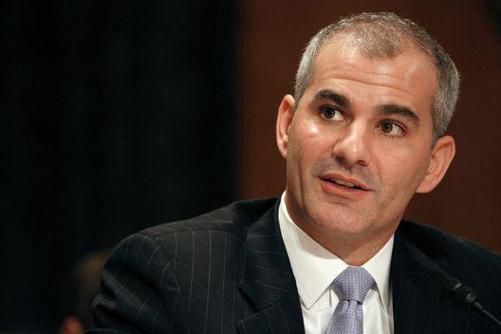

Assistant Secretary of Defense for Special Operations and Low Intensity Conflict Michael Vickers.

CHIP SOMODEVILLA/GETTY IMAGES

President Barack Obama makes a point during a meeting in the Situation Room of the White House about the mission against bin Laden. National Security Advisor Tom Donilon is next to the president.

OFFICIAL WHITE HOUSE PHOTO BY PETE SOUZA

Director of the National Counterterrorism Center Michael Leiter, who led a Red Team to review the intelligence on the Abbottabad compound just a few days before the raid.

CHIP SOMODEVILLA/GETTY IMAGES

CIA Director Leon Panetta and his chief of staff, Jeremy Bash, watch a screen intently during the Navy SEAL raid that killed bin Laden.

CIA

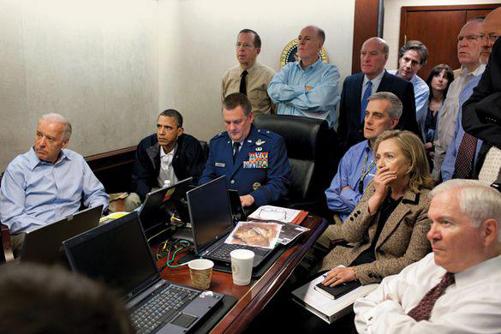

President Obama and Vice President Biden in the White House, May 1, 2011. Seated, from left, are Brigadier General Marshall B. “Brad” Webb, Deputy National Security Advisor Denis McDonough, Hillary Clinton, and Secretary of Defense Robert Gates. Standing, from left, are Admiral Mike Mullen, National Security Advisor Tom Donilon, Chief of Staff Bill Daley, National Security Advisor to the Vice President Tony Blinken, Director for Counterterrorism Audrey Tomason, Assistant to the President for Homeland Security John Brennan, and Director of National Intelligence James Clapper.

OFFICIAL WHITE HOUSE PHOTO BY PETE SOUZA

10

THE SECRET WARRIORS

S

EVERAL HUNDRED MILES

off the coast of Somalia, as dusk deepened over the Indian Ocean, on the sweltering evening of April 13, 2009,

three shots rang out. All the bullets found their targets: three Somali pirates in a small lifeboat bobbing on the darkening sea.

For the past five days the pirates had held hostage Richard Phillips, the American captain of the container ship

Maersk Alabama

. President

Obama had authorized the use of deadly force if Phillips’s life was in danger. Unbeknownst to the pirates, days earlier a contingent of Navy Sea, Air, and Land (SEAL) teams had parachuted at night into the ocean near the USS

Bainbridge

, which was shadowing the pirates. The SEALs had taken up positions on the fantail of the

Bainbridge

and were carefully monitoring Phillips while he was in the custody of the pirates. One of the pirates had just pointed his AK-47 at the American captain as if he were going to shoot him. That’s when the SEAL team commander on the

Bainbridge

ordered his men to take out the pirates. Three SEAL sharpshooters fired simultaneously

at the pirates from a distance of thirty yards in heaving seas at nightfall, killing them all.

Obama called Vice Admiral William McRaven, the leader of Joint Special Operations Command and of the mission to rescue Phillips, to tell him, “Great job.” The flawless rescue of Captain Phillips was the first time that Obama—only three months into his new job—had been personally exposed to the capabilities of America’s “Quiet Professionals,” the secretive counterterrorism units of Special Operations, whose well-oiled skills he would come to rely upon increasingly with every passing year of his presidency.

It was not always so. Joint Special Operations Command was born out of the ashes of an American defeat in the deserts of Iran three decades before Obama assumed the presidency. When fifty-two Americans were held hostage at the U.S. embassy in Tehran in 1979 by fervent followers of the ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, President Jimmy Carter authorized a mission to rescue them. The mission was never going to be easy: it entailed flying almost one thousand miles into a remote desert region of Iran, traveling undetected to Tehran, and then rescuing the hostages, who were guarded by Iran’s fanatical Revolutionary Guard.

Operation Eagle Claw, sometimes referred to as Desert One, was doomed almost as soon as it started. Three of the eight helicopters that flew the mission developed mechanical problems because of sand storms. The mission was aborted, and then one of the five remaining working helicopters collided with an American transport plane during a refueling in the Iranian desert,

killing eight American servicemen. It was, in U.S. military parlance, “a total goat fuck.” Back in Washington, a rising CIA official in his early forties named Robert Gates was at the White House watching with mounting dismay as the whole disaster unfolded.

A Pentagon investigation found myriad problems with Operation

Eagle Claw: Interservice rivalries meant that the army, air force, navy, and marines all wanted to play a role in this important operation, and even though the four services had never worked together before on this kind of mission, each service got a piece of the action. An overemphasis on operational security prevented the services from sharing critical information with one another and also prevented the entire plan from being written down so that it could be studied overall. The navy allowed poor maintenance of the mission helicopters, the air force pilots who flew the mission had no experience in commando operations, and there was no full-scale rehearsal of all the elements of the plan.