Marching With Caesar - Civil War (7 page)

Read Marching With Caesar - Civil War Online

Authors: R. W. Peake

In the 10th, the biggest change came with the return of Crastinus as Primus Pilus, but it was with some trepidation that I answered his summons for a meeting of the senior Centurions of the Legion, since I did not know what frame of mind he would be in. For all I knew, the months he had spent in retirement were the happiest of his life, and I could think of all kinds of possible outcomes if that was the case, none of them good. Being Primus Pilus, Crastinus held absolute control over all of us, and if he was angry at his recall, he could in turn make all of our lives miserable. Entering his tent, my heart sank at the sight of his scowling face, with its livid scar along the jawline, courtesy of a Nervii sword. He gave no sign of recognition, save for a curt nod as I entered to join the other Centurions who had already arrived. Luckily I was not the last to arrive, sparing me the scathing tongue-lashing with which Crastinus skewered the unfortunates, obviously having spent some of his time in retirement coming up with more inventive terms to describe their mothers, using curses I had never heard before from his lips. I also took notice of the fact that the customary cups of wine were nowhere in sight, further increasing my suspicions that our Primus Pilus was not particularly happy to be back with us.

Once we had settled in, he began speaking. “All right, there’s no need to go over why I’m here. Caesar commanded it and that’s that. All I have to say about it is…”

He paused, and I found myself holding my breath, waiting for him to unleash some sort of invective aimed at Caesar and the army. But as usual, Crastinus was a man of surprises.

“Thank the gods,” he shouted, his battered face creasing into a smile. “I was bored out of my fucking mind! I was almost ready to show up at the next

dilectus

and start over as a

tiro

! Farming is the worst job in the world, and I hope I never see another plow as long as I live!”

There was an explosion of air as I realized I was not the only one holding my breath, and we laughed uproariously, as much from the release of tension as at Crastinus’ wit. Amid the laughter, Crastinus reached down from behind his campaign desk where he had hidden an amphora of Falernian wine and enough cups for all of us. Within moments, we were toasting his return and laughing at his tales of woe as yet another failed farmer. We passed the evening drinking to his failure as a farmer, and everything else we could think of, and I vaguely remember weaving my way back to my own tent, aglow with a happiness that was fueled as much by the relief I felt that Crastinus was happy to be back as it was by Bacchus. The next morning was a slightly different story, and I am afraid the Cohort suffered from my hangover as much as I did. Such are the privileges of rank.

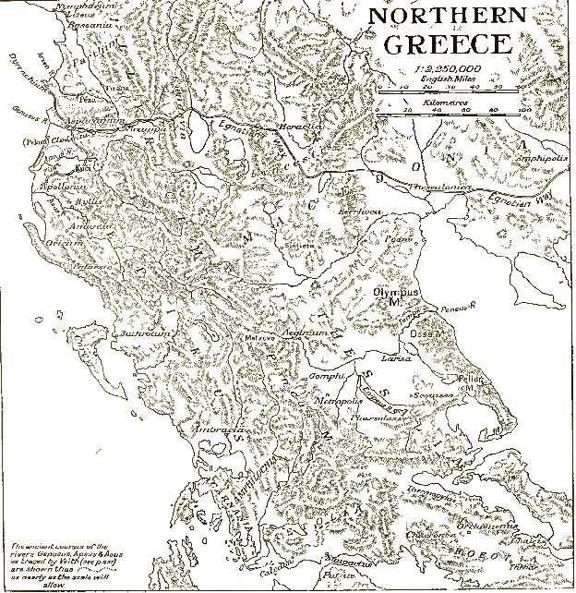

Chapter 2- Greece

We did not stay in Massilia long, and I will not spend time recounting the siege and conquest of the city, mainly because we played no real part in it. Once the city was occupied, with Caesar acting with his usual clemency, a policy that was growing increasingly unpopular with the army, he issued orders for us to begin the long march back to Italia, all the way down the peninsula to the heel and the port city of Brundisium. This was going to be the port of embarkation for the invasion of Greece, where Pompey was gathering his own army, building fortifications at strategic points along the coast in preparation for our crossing. This was the longest march we had ever undertaken at this point, but Vibius and I were excited to finally see Italy; despite the fact we were not going to enter Rome, we would be passing nearby, and we talked about the sights we would see. We would also be passing through Campania, and depending on our exact route, I thought I might stop in the town where my father came from to meet the kin I had never seen before. Despite the anticipation of seeing the home province for the first time, none of us was looking forward to being on the march for more than a month. Even with the roads that are the best in the known world, day after day of marching in formation wears a man down, no matter how fit he is. My job as Pilus Prior meant that I had to be constantly on the alert for men falling out on the march, either because of exhaustion or because some comely wench caught their eye. The farther east we marched, the more settled and prosperous the land, and it was somewhat unsettling to realize just how dingy and poverty-ridden the regions we had originally come from were when compared to the peninsula. Crossing the Rubicon, I know that I for one was struck by the moment. After all, this river had ultimately launched the civil war. I must say that I was not impressed, expecting something more substantial than the muddy stream that we waded across without having to lift our shields above our heads. It didn’t seem to be much of a barrier, or much of a symbol to use, as the line over which no general could march his troops. Now, I know this has caused some confusion. Indeed, I spent the equivalent of many watches trying to explain it to Gisela because I will admit that it is puzzling. Her question was simple; if no general could cross the Rubicon with an army, how did that explain when a general was given the honor of a triumph in Rome, and he could march at the head of his army through the streets of the capital? I had wondered about this myself, finally working up the nerve to ask one of the older men, who laughed and said that he had asked the same question. It is a matter of form more than anything else. A general is not allowed to lead an army over the Rubicon. However, if he crosses first and enters the capital, then summons his army, that is acceptable. But to ride at the head of an army is expressly forbidden, since it signals evil intentions against the Republic. When I had explained this to Gisela, she snorted in her usual contempt for some of our finer points of custom and tradition.

“So he can ride ahead, lull your stupid fat Senators into believing that he has only good intentions, then summon his army to descend on Rome?”

When I grudgingly agreed that this was one way to look at it, she simply shook her head in wonderment. “How you lot managed to conquer most of the known world is beyond me.”

I knew better than to argue the point with her, and in truth, sometimes I wondered myself.

~ ~ ~ ~

Such was the tone of my thoughts wading across the muddy river. I had left Gisela and the baby behind, and it was at moments like these when I thought of times spent with her that the ache of loneliness was the worst. While the rankers brought their women along with them wherever they went, it was not seemly for a Centurion of my rank to do the same, meaning Gisela and my child were far away, safe enough, but I longed for their company at night when the army bedded down. However, these were not thoughts I could express to anyone, not even Vibius, so I would sit in my tent at night, brooding over the daily reports and ration requests. It was a mark of my frame of mind that I insisted on doing these myself, rather than let Zeno do them like I normally did, but I needed something to keep my mind busy and away from thoughts of my family. I would make the rounds of the fires at night, trying to present a normal front to the men, but there are no secrets in the army, and I could tell they knew something was bothering me. Still, I was not willing to talk about it with anyone, except that Vibius was unwilling to accept that and persisted in showing up at my tent every evening, demanding to know what was bothering me. Finally, a couple of days after we crossed the Rubicon, I broke down and told him, more out of exasperation than anything else. We were sitting in my tent, and he looked across my desk at me somberly, his wine cup in his hand. I am not sure what I was expecting, yet he did not mock or tease me, the normal reaction any man got when he displayed any type of emotion or behavior that his comrades considered soft.

Instead, he nodded and said simply, “I thought so.” He suddenly stood and turned away so that I could not see his face as he continued, “Titus, I know how you feel, trust me in that. Remember how I felt about Juno?”

This was the first time I had heard her mention her name since that awful time back in Hispania, and I took it as a sign that the wound was no longer raw and open, but had begun to scab over.

“I remember,” I said quietly, and I thank the gods that I caught myself from adding that it was different, because I know that would have wounded Vibius deeply.

“I wish I could say that it gets easier, but it doesn’t.” He drank deeply, then turned to me, shrugging with a sad smile on his face.

“Well, if you’re trying to cheer me up, you’re doing a piss-poor job of it,” I said, only half-jokingly, but he laughed anyway.

Then he turned serious again and said simply, “I just wanted you to know that I know how you feel.”

“Thank you, Vibius. It does help, a little.”

There was a silence, then Vibius cleared his throat and awkwardly set the cup down on the desk. “Yes, well. I’ll be off then, Centurion.”

“Thank you again, Vibius. It’s good to know I still have a friend.”

“Always,” he replied simply, then turned and left the tent.

Oh, how I wish those words had held true.

~ ~ ~ ~

One of the small benefits of marching in Italia was that we no longer had to construct the standard “marching camp in the face of the enemy” as it is called in the manuals, meaning that we would be settled down earlier in the day than usual for us. While this was a boon for the men, for the Centurions it was a never-ending source of headaches because idle time is our worst enemy since it gives the rankers more time to get into some sort of mischief, and the number of men on charges was getting to be a serious matter. I called for my Optio, glad at least that I finally had someone in the position that I knew I could rely on totally, my old comrade Scribonius. When I had first been made Pilus Prior, I was forced to name a man named Albinus as my Optio, for reasons that I no longer even remember. He had been almost useless; a weak, indecisive man who showed little initiative and even less enthusiasm for his job, thinking of it as a benefit rather than a responsibility. Unfortunately, his performance was not substandard enough for me to relieve him without a major headache, but the gods smiled on me by striking him down with the bloody flux, and he had the good grace to die shortly before we left Massilia. This time I was not going to make the same mistake, immediately approaching Scribonius, who had turned out to be one of the best choices I could have made, not only because he was one of the most popular men in the Century, but in the whole Cohort as well. His courage was unquestioned, but most importantly he was respected for his fairness and his ability to use reason instead of brute force. That did not mean he was soft; he could crack skulls with the best of us, yet he did not use force as his first resort, like some of the other officers. Now, he stood before me and I was sure my expression mirrored his, one of exasperation and a wry amusement at the ingenuity of the men. One of my saltiest veterans, Figulus, had gone missing, despite the best attempts of both Scribonius and I to keep the men too busy to think up ways to sneak out of camp. Figulus had been a close companion of the late Atilius, but possessed a shred more common sense, usually knowing when to rein in his wilder impulses. He had also been one of the men Caesar recalled and like Crastinus, had expressed his joy at being back in the army, civilian life proving not to be to his taste. But now, the fat countryside with the pleasant towns and pretty girls were proving too much of a temptation and he had managed to slip out of camp to go sample the local wares.

“The best I can tell, he managed to hide himself in the supply wagon that came this afternoon,” Scribonius reported. I considered this, stepping outside to look at the sun to calculate the time. There were still a couple of watches of daylight, but we were scheduled for an evening formation, the Primus Pilus deciding to hold it as a deterrent for just such behavior, and the penalty for missing formation is a flogging. Knowing that, I was fairly sure that Figulus had every intention of returning before evening formation.

“Very well. We’ll hold the report until the last possible minute. As long as he makes it back before formation, then we won’t have to write him up.”

“Yes, sir. But we can’t just let him get away with sneaking off like that.”

“Don’t worry,” I said grimly. “He won’t. I’ll see to that myself.”

~ ~ ~ ~

As it turned out, I was right; Figulus magically reappeared, getting past the sentries on the gate about a sixth of a watch before evening formation. I saw him striding back to his tent, looking immensely pleased with himself, and I smiled, but it was not a friendly smile.

“Figulus!” I barked his name, pleased to see the expression on his face change instantly as he froze in mid-stride. “Get over here, now!”

He immediately turned and ran to me, stopping and coming to

intente

, eyes riveted to a point above my head. “Gregarius Figulus reporting as ordered, Pilus Prior,” he rapped out the standard response.

To someone who did not know Legionaries in general and Figulus in particular, all would have appeared normal, but I could detect the hint of worry in his voice.

“How are you, Figulus?” I asked with a tone of concern, a senior Centurion checking on the welfare of his men, deepening Figulus’ confusion.

“Sir?” His tone and manner was one of uncertainty, appearing confused by my solicitous tone, precisely the effect I was intending.

“I just haven’t had a chance to talk to you lately, and you’re one of the veterans that were part of our

dilectus

and came from Pompey’s Legions. You were there when Vinicius bought it, weren’t you?”

The mention of our old Optio’s name brought a shadow of sadness across the older man’s face, and I instantly regretted bringing up the unpleasant memories associated with his name. We had watched him incinerated in front of our very eyes, during our very first campaign in Hispania under a then little-known Praetor named Gaius Julius Caesar. It was to Vinicius I owed my first position as weapons instructor; he had taught me almost as much as Cyclops had about how to fight.

“Yes, sir,” he said quietly, and while his face remained expressionless, I could see his eyes soften at the memory.

“There are just so few old-timers left that I try to keep an eye out for all of you, and we haven’t had a chance to talk lately. So, is everything all right? Your old bones holding up to the long march?” I asked this in a slightly teasing tone, trying to lighten the mood.

I saw his chest puff out, indignant at the implication that his age was catching up with him.

“Pilus Prior, I’ll march any man’s cock into the dirt!” he exclaimed, and I laughed.

“I know you would, Figulus. I just wanted to make sure all was well.”

“Right as rain, Pilus Prior,” he had adopted the same bantering tone that I had, an old veteran wise in the ways of flattering his superiors and giving them exactly what they wanted to hear.

“Good, I’m very glad to hear it. Very well, carry on Figulus. Remember we have evening formation in a few moments.”

He saluted. “Yes, sir. Haven’t missed a formation yet, sir.”

When he turned to march away, I could see the relief and joy at having gotten away with his misdeed written all over him.

“You didn’t really think you would get away with it, did you?” I said softly, gratified to see his body go rigid with shock as he came to an abrupt halt.

After a moment’s hesitation, to compose himself I was sure, he executed an about-face, his face a mask. “Sir? I’m not sure I understand the Pilus Prior’s question.”

The friendly face I had been wearing was gone, instead I stared at him with all the cold fury I could muster, and I found to my own small surprise that not all of it was feigned. I was actually angry with Figulus, although he had not done anything more egregious than a half-dozen other men in my command over the last several days, or any man in the Legion for that matter. Still, I could not let Figulus’ deed go unpunished, but I also did not have any desire to have him flogged, because truth be told, I did have a soft spot in my heart for the men who had marched with me all these years.