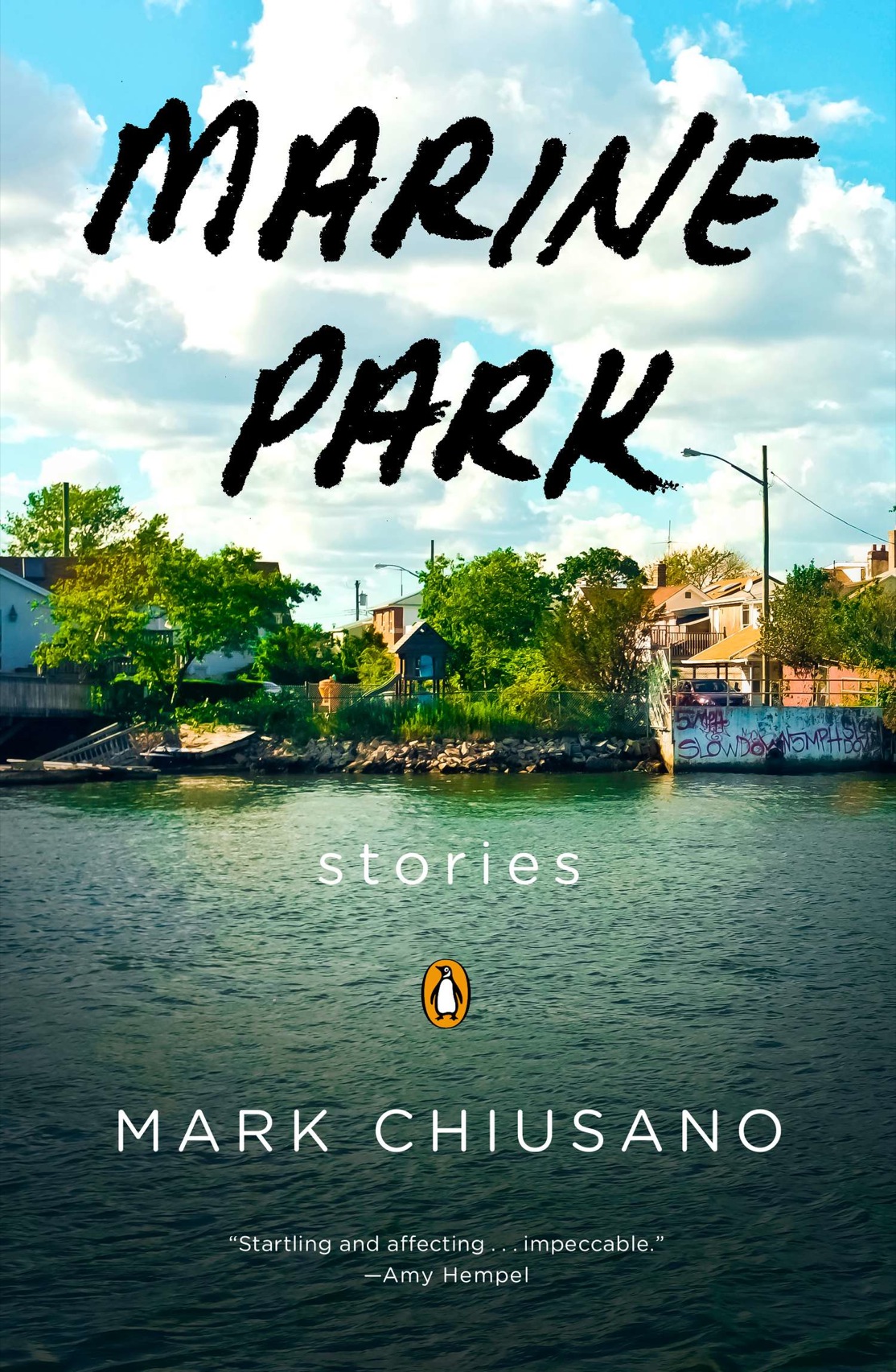

Marine Park: Stories

PENGUIN BOOKS

MARINE PARK

MARK CHIUSANO

is a graduate of Harvard University, where he was the recipient of a Hoopes Prize for outstanding undergraduate fiction. His stories have appeared in

Guernica

,

Narrative

,

Harvard Review

,

and online at

Tin House

and

The Paris Review Daily

. He was born and raised in Brooklyn.

Praise for Mark Chiusano's

Marine Park: Stories

“In clean, honed prose, Mark Chiusano gives us an intimate tour of a neighborhood of Brooklyn not offered up in fiction before. His explorations of loyalty within a family, and the breach of it, are startling and affectingâhis sense of story is impeccable.

Marine Park

is a debut worth a reader's close attention.”

âAmy Hempel, author of

The Collected Stories of Amy Hempel

“The stories in

Marine Park

are funny and touching and elliptical, and all about coming of age at the edge of the city and on the margins of the good life, with some moving forward and others left behind. Mark Chiusano is wonderful on how our minds can be elsewhere even when we wish to be wholly present, and on the oblique ways in which we therefore often have to signal our indispensability to one another.”

âJim Shepard, author of

You Think That's Bad

“One of the most subtle, tender, emotionally powerful books that I've read in a long time. Set mostly in Brooklyn, but its subject is the whole of America. If you've never been to Marine Park before, by the end of this collection you'll feel like you'd lived there your whole life. This is a stunning debut.”

âSaïd Sayrafiezadeh, author of

When Skateboards Will Be Free

and

Brief Encounters with the Enemy

“Here's the spirit of dear Sherwood Anderson in Mark Chiusano's

Marine Park

, another village brimming with all of the odd drama of families and loners. There is something a little old and wise in this talented writer's debut. At times the stories read like the news, letters from a friend, and at times the tales seem elegiac glimpses of a lost world. Mr. Chiusano is writing family from the inside out and he makes this world an aching bittersweet pleasure. Here is the kind of affectionate particularity which marks a fine writer.”

âRon Carlson, author of

Return to Oakpine

“In

Marine Park

, Mark Chiusano shines a light on lives that are too often left in the dark. He shows us, with humor and deep-hearted compassion, the complexities of growing up and growing old in the blue-collar shadows, and he gives us, story after story, the chance to see ourselves in his longing, hopeful characters. This is a wise and affecting collection, and it marks the arrival of a voice we've not heard until now, one that will carry through the streets and alleys of contemporary literature for years to come.”

âBret Anthony Johnston, author of

Remember Me Like This

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

A Penguin Random House Company

First published in Penguin Books 2014

Copyright © 2014 by Mark Chiusano

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

The following magazines published earlier versions of several stories in this collection:

The Bad Version

(“Vampire Deer on Jekyll Island”),

Blip

(“Why Don't You”),

The Harvard Advocate

(“Air-Conditioning,” “Car Parked on Quentin, Being Washed,” and “We Were Supposed”),

The Harvard Crimson

(“The Tree”),

Harvard Review

(“To Live in the Present Moment Is a Miracle”),

Narrative

(“Heavy Lifting”), and

The Utopian

(“Shatter the Trees and Blow Them Away”).

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Chiusano, Mark.

Marine Park : stories / Mark Chiusano.

pages cm

eBook ISBN 978-1-101-63203-1

1. Marine Park (New York, N.Y.)âFiction. I. Title.

PS3603.H5745M37 2014

813'.6âdc23

2014006051

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Version_1

For my mother and father, and for Scott

Praise for

Marine Park: Stories

TO LIVE IN THE PRESENT MOMENT IS A MIRACLE

SHATTER THE TREES AND BLOW THEM AWAY

L

orris turned the key in the garage door lock, and I pulled the door up. Look, said Lorris. Icicles, he said. They were hanging from the metal runner on the bottom.

There were three shovels in the back of the garage and Lorris picked two, grasping each at its center to test the weight. He handed me the longer one, the slightly heavier one, for breaking up ice patches. He was too small for that. Then we closed the garage door.

Outside, on Avenue R, the snowdrifts went up as high as the information boxes on the bus stop poles. The fire hydrants were completely buried. We tried to put our boots in the few footsteps in the middle of the street. If we dug down we'd be walking on the double yellow line. The plows weren't out this early. I carried the shovel on my shoulder, blade up. Lorris dragged his behind him. Every once in a while he'd pick it up to knock off the snow sticking to the end.

At the first house, Lorris waited at the bottom of the stairs. You go, he said. I took off my glove to ring the bell. Shovel your walk? I asked the old woman who answered. Kenneth, she yelled behind her, before she disappeared into the warmth. A man appeared in his undershirt. Move along now, he said.

We only went to houses with driveways, for the possibility of extra work. Ones with cars in front, to say that someone was home. Often the windows with no Christmas decorations, because non-Christians paid better for this kind of thing. The rest of them shoveled little pathways down their own steps on the way to mass. Lorris was good at spotting mezuzahs nailed to the wooden frames.

At the third house a little girl answered the door. She was even younger than Lorris. She still had her pajamas on. Is your mom home? I said. Lorris looked up from the bottom of the stairs. A beautiful lady came up behind the girl, wrapped in a wool blanket. Is something wrong? she asked. Do you need some shoveling? I said. I pointed at my shovel with my bare hand.

The lady looked behind her, into the house. What're you charging? she said.

Twenty bucks, I answered. I could hear Lorris suck in his breath.

I'll give you ten, she said.

I need fifteen, I told her. She played with the hair on top of the girl's head. Clean our driveway out too? she asked.

We were always good shovelers, Lorris and I. I think we came out of the womb doing it. Lorris used the small one for finesse workâthe stairs, the edges under railings, the wheel paths of cars. He did the salt, if people had it for us, though he made me carry the bags from their doorsteps to strategic central locations. I didn't like my gloves getting blue from the chemicals. I was the heavy lifting man, could carry three times my shovel's maximum load.

At the corner of Quentin, off Marine Park, a Jeep was stuck in the crosswalk. There were other crews of kids carrying their shovels on their shoulders. A big-chested man rolled down the passenger-side window and shouted into the cold: Twenty-five bucks if you get us moving. Two crews raced across the street to get there first, and because they made it at the same time, they both just started digging. A couple of early drinkers came out of the Mariners Inn without coats on, trailing steam behind them, to watch. Lorris pulled on my sleeve and said, I think Red Jacket's the best. We leaned on our shovels while the Jeep's wheels spun and shrieked, the gray slush shooting up into the shovelers' faces. One kid was jamming the shovel blade right into the rubber of the tire, and the passenger-side window rolled down again, and the man said, Hey, knock that off.

Once the Jeep lurched forward a little, a twenty-dollar bill came flying out the window and landed in the snow. Two kids dove on top of it. One of them had a Hurricanes football sweatshirt on. On the back it said,

GIVE 'EM HELL

. The Jeep screamed away, toward Avenue U and the Belt Parkway. Come on, Lorris, I said.

It was twelve o'clock when we finished our usual streets. Someone with a snowplow was revving his engine on Thirty-Sixth, ruining our business. A group of three men, in heavy blue sweatshirts, jogged by us with shovels. The one in the front had hair on his face. 'Ta boys, he said. Can we go home now? Lorris whined, hitting my back with his shovel handle. Almost, I said. He unwrapped the Rice Krispies bar he kept in his pocket for emergencies.

The house didn't have a doorbell. You could have told that even before you were on the stoop. Part of the front window had cardboard over it. Come inside, the man said when he opened the door. We're not supposed to, Lorris called from the bottom of the unshoveled stairs. Shut up, I told him. He followed my boot prints up.

Get the snow off your feet, the man said. I don't want water bugs in my house, he said. We stamped our feet on the rubber mat. We followed his wide back through the dark, into the kitchen. Here, he said, and put two mugs in our hands.

We sat at the kitchen table. Lorris looked at the man, and the man glowered down at him. His chest was sweaty and his firehouse T-shirt stuck to it, bleeding black through the blue. His crucifix chain hung over his shirt. I need you to do my backyard, he said.

Out the screen door, we surveyed the job. Deep, thick drifts, nowhere for good foot purchase. Fences too high to throw the snow over. A hundred dollars for the whole thing, he said.

We waded into the middle. Lorris and I started back to back. The man had put a windbreaker on and was sitting in a foldout chair with his feet up, watching us. That's it, he said. That's right. Our shovels hit the ground. We pushed off from each other, Lorris shoveling his snow to my side, where I snared it and tossed it off under the high porch. That's it, the man said.

It got so hot that we took off our jackets. The sun was higher and higher. The sweat was dripping from the blue beanies our mother made us wear. When I looked up at the man sitting there his mouth was slightly open, like he was waiting for something to happen, like he didn't think that we would finish. But we got all the snow off. We shoveled that yard until just the bare garden was showing beneath it, the soil hard as concrete that when we reached made our shovels ring.