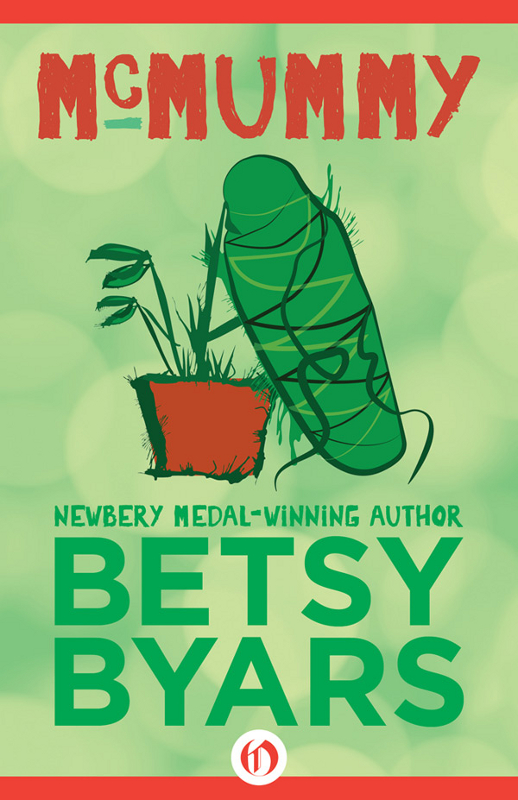

McMummy

Authors: Betsy Byars

Betsy Byars

For Anna

M-Mummy Pod

I

T WAS HARD TO

explain the Mozie look to an adult, but Batty Batson had to try because his mom thought he was just being cruel when he laughed at his sister’s piano recital.

“I couldn’t help laughing, Mom. I didn’t want to. I just couldn’t help it.”

“Some things are not funny.”

“I know. I know …”

“You don’t seem to.”

“Well, I do.”

“Then why did you laugh?”

He decided to tell the truth. “Mozie’s look made me do it,” he explained.

“What are you talking about? What look?”

“I’m not sure I can describe it.”

“You had better try, young man.”

“Oh, sure, if you put it like that.” There was something about being called young man that always made Batty get serious.

“Well, we got to the recital, and we were going to be perfect—clap when we were supposed to and sit still when we were supposed to do that.”

His mother waited.

“Well, as you know, Linda was the first one. She sat down on the piano bench, and you know how sometimes cushions make a funny noise when somebody sits on them, like

Ffffffff—

”

Batty started laughing remembering it, but he wisely swallowed his laughter.

“So I didn’t look at Mozie, because I did not want to laugh—”

The swallowed laughter came up and burst from him. He glanced up at his mother. He wished he hadn’t done that because his mother had a look of her own—his least favorite look.

He made a super effort to get control of himself. It always got the laughter out of his system, when he was with Mozie, to fall down on the ground and throw himself around. He knew his mother wouldn’t be as tolerant of that kind of behavior as Mozie was.

“So she—”

Batty had to stop again. This time he got his face under control by looking down at his shoes. Batty glanced up at his mother. He felt his face was in neutral now.

But the knot of laughter was still inside. He could feel it. He knew how volcanoes felt just before they erupted.

“After the cushion went

Ffffffff …

”

Once again, he couldn’t continue. The pressure of the inner laughter brought tears to his eyes. His shoulders began to shake.

His mother waited. His mother had the patience of a rock. She could outwait eternity.

Finally—at last—Batty got himself under control.

“See, Mom, it’s a look Mozie gets on his face when something funny happens. He gets this look on his face like he knows I’m going to laugh, and he knows

I know

he knows I’m going to laugh, and the worst thing I can possibly do is laugh. And I can’t help myself, Mom. I laugh.”

His mother looked at him. “So, why did you look at Mozie then? If you knew it was going to make you laugh?”

“I didn’t. I didn’t. But knowing the look was on his face, even if I couldn’t see it, was as bad as seeing it. That’s all I can tell you.”

“Go to your room.”

“Mom—”

“Go—to—your—room.” When his mom started putting extra spaces between her words, Batty knew it was hopeless.

“I’m going.” Batty began walking backward as a pledge of good faith. “But Mom, I promised Mozie I would go with him to Professor Orloff’s greenhouse after supper. I always go with him. Mozie has to look after his plants, and he can’t go there alone because last time he went he saw this very strange thing on one of the plants—”

“You’re not going anywhere. You’re staying in your room.”

“Mom, I have to go. There’re things growing in there, and I don’t mean petunias. Mozie can’t go by himself. His life genuinely may be in danger.”

“Go—to—your—room.”

“I have to at least call and warn him.”

“I’ll take care of it.”

“Mom, he’s got to have time to get someone to go with him. There are strange, strange plants in there. Remember that movie? What was the name? You remember, a plant that ate people? You wouldn’t let me watch it?”

Silence.

“Mom, I didn’t want to tell you this because I didn’t want you to worry, but the thing Mozie saw—the thing that scared him—Mozie saw a kind of pod. I guess you’d call it a pod. Only it wasn’t shaped like, you know, beans. It was shaped more like—well, a mummy, you know, kind of little at the top and then getting wider, like for a body.

“Mozie said it was covered with very, very fine hair like Grandma’s cheeks.”

Even this detail didn’t impress his mother. He continued.

“Remember when he came over to the house yesterday? Did you happen to see him? He was waiting on the steps for me to get home from the dentist. Did you see him?”

No answer.

“Because he came running over to the car and he had a very strange look on his face.”

Now his mother spoke. “

The

look?”

“No, Mom, of course not. This was a look I’d never seen before, and I’ve known Mozie since first grade. I said, ‘What’s wrong?’ because I knew immediately something had happened. He drew me aside. He said, ‘There’s a m-mummy pod in the greenhouse.’

“I thought he said McMummy and I go, ‘Man, you been eating too many hamburgers.’”

His mother did not look amused at his humor.

“Mozie said, ‘I am telling the truth. There is a m-mummy pod on the big plant in the back. Come with me tomorrow. See for yourself.’ He said, ‘Promise, because I’m not going there alone.’

“I said, ‘I promise.’ It was an actual promise.” He crossed his heart as earnestly as he used to when he was little.

“I know you are very big on keeping promises because when I promised not to eat anything chewy with my new braces and you came in and caught me eating a Snickers bar, I honestly thought you were going to hit me.”

His mother looked at him, and he trailed off. For a moment he hoped she was softening. But then she said, “You will go to any lengths, won’t you, make up any story, no matter how fantastic, to get out of the house.”

“Mom, it’s true. I didn’t make it up. If I were going to make up something, I would make up something you would believe like homework or going to the library, I wouldn’t make up a McMummy pod because there is no such thing.”

“Exactly. Now go to your room.”

“Mom, can I ask you one thing?”

She waited.

“Mozie and I are baby-sitting Friday night and I need to tell him if I can’t go.”

“You can’t go.”

“Mom, these are jobs! You want me to be a success in life, don’t you? You want me to get off the dole, don’t you? You—”

“I want you to go to your room. Your father will be in to talk to you when he gets home from Atlanta.”

“About what?”

“Your sister’s piano recital.”

“Oh, that.”

Now Batty went.

M

OZIE WALKED UP THE

steps to Batty’s house. He took a deep breath and rang the bell.

Mozie hoped Batty himself would answer instead of one of his sisters—especially Linda. She would still be mad about the recital and probably wouldn’t let him in.

The door opened. It was Mrs. Batson. This was better than Linda but worse than one of the other two sisters.

Mozie cleared his throat. “Could I speak to Batty? I forgot to tell him something.”

“Who?”

Mrs. Batson’s voice was cold. Mozie remembered that she didn’t like Batty to be called Batty. Her husband, Mr. Batson, was also called Batty, so now she had the burden of living with Little Batty and Big Batty, which Mozie knew couldn’t be pleasant.

To everybody else in the world they were Mozie Mozer and Batty Batson, but to Mrs. Batson, they were Robert and Howard.

Mozie corrected himself at once. “Could I speak to Robert, please?”

“No.”

“Isn’t he here?” Mozie tensed with alarm. “Mrs. Batson, he and I are going up to Professor Orloff’s. I have a job watering his greenhouse and, for reasons I won’t go into, Batty has to go with me today. When will he be back? I’ll just wait for him unless he’s going to be very late—he will be back before dark, won’t he?”

“Robert has not gone out, Howard. He is in his room.”

“Oh, good. What a relief. I’ll go up.”

Mrs. Batson seemed to expand so that she filled the whole doorway, making it impossible for Mozie to get in the house. Her voice—though it had been stern enough to start with—got sterner.

“Howard, I want to say something to you.”

“Yes, of course, but make it—” He was about to add “snappy,” but, fortunately for him, she interrupted.

“Howard, I want you to stop giving Robert looks.”

Mozie was so stunned he couldn’t answer for a moment. He had never actually given Batty a look, and certainly not at his sister’s piano recital. Once he glanced at Batty in assembly when the Suzuki violins had gotten off to a bad start on “Mississippi Hotdog,” but it wasn’t a look. The fact that Batty laughed didn’t make it a look.

Mrs. Batson waited a reasonable length of time for him to recover and then asked, “Did you hear me?”

“I don’t give him looks. He thinks I give him looks, b-but I don’t. I really don’t even have a look, if you want the truth. I couldn’t even give him a look if I wanted to. I mean, this

is

my look, Mrs. Batson. My face just looks like I’m giving a look, even though I don’t have a look to give. I m-mean, I can’t—”

The only time Mozie ever stuttered was when he was trying to explain something to Batty’s mom—or when he saw a mummy pod.

Mrs. Batson interrupted. “I do not have time to listen to foolishness.”

“It’s not foolishness—it’s the truth,” he began. Then, because the situation was so desperate, he decided to beg.

“Mrs. Batson, please, please, Robert’s got to go to the greenhouse with me. He’s got to!”

“Robert only has to do one thing this evening, and that’s stay in his room. His behavior at the recital was inexcusable.”

“Mrs. Batson, I can’t go out to the greenhouse by myself. I didn’t want to mention this, but yesterday when I was there—remember Batty was at the dentist?—well, yesterday, I saw this sort of pod. It was shaped like a mummy, and, um, I know you’re going to think I’m being foolish, imagining things even, but the pod seemed to move, to turn in my direction like, well, radar.”

He swallowed.

“I’m really, honestly scared, Mrs. Batty—I m-mean Mrs. Batson.”

He closed his eyes, trying for self-control.

“I mean, once you’ve seen a mummy pod, and it sort of turns in your direction, you don’t ever want to see it happen again. If Batty’s there, he can stop me from—”

“I’m not going to listen to any more of this talk about a mummy pod. You boys have gone too far this time. Good-bye, Howard.”

“Mrs. Batson, please! Just let me say one more thing.”

She waited in a silence so cold it seemed to chill the air.

“Mrs. Batson, I know you are a person of honor because Ba—Robert has told me that many, many times, and you would—I am sure—always want Robert to keep his word—his promise.”

He swallowed, and the sound was like a word out of a guttural foreign language.

“Now,” he continued, “I think I see a way that Robert could keep his solemn word to me as well as be punished. That way, Mrs. Batson, would be for you to let him go with me this afternoon and start his punishment tomorrow—”

“The punishment has already started. Good-bye, Howard.”