Memnon (36 page)

Authors: Scott Oden

Memnon glanced sidelong at the eunuch, frowning as though such an idea never occurred to him. “Philip, you mean?”

Hermeias’s silence spoke more plainly than any explanation.

On stage, the

exodos

unfolded and the actor playing Aeschylus, now free of Hades’ realm by the comic misdeeds of Dionysus and his servant, delivered his final lines. “And remember,” the fellow said, puffing himself up, “let not that villainous fellow—that liar, that clown!—sit upon my throne, not—”Memnon’s pawn chose that moment to strike.

From the corner of his eye, the Rhodian saw a man approaching from his left, over the eunuch’s shoulder. He looked no different than the other theatergoers, cloak-wrapped, his features ruddy from the chill air and from drink, driven by necessity to seek the privy. He pulled a dog-skin cap down over his balding pate. As he passed close to Hermeias, though, Memnon saw a spasm of hate contort the man’s face. Iron flashed.

“Death to the tyrant!” the assassin roared.

Memnon was in motion as the words left the man’s lips, dragging the startled Hermeias out of his attacker’s path. Gracelessly, the eunuch tumbled to the stone floor. “Guards! Protect your king!” The actors and the crowd recoiled; a woman screamed.

The assassin lashed out, his blade gashing the Rhodian’s left biceps; before he could draw back and strike again, Memnon caught his knife-hand and twisted it, feeling bones break under his fingers. The weapon clattered to their feet. The man bellowed in agony and made to claw at Memnon’s eyes, but the Rhodian ducked his head and thrust the fellow away, pushing him into the path of the onrushing guards.

Kritias reached him even as the failed assassin turned to flee. The captain’s spear took him high, staving in his breastbone and punching through his body. The man crashed to the ground, writhing, spewing bright blood and curses as he died in sight of the gods.

More guards spilled into the theater, blocking exits and holding the milling crowd at bay while the sponsors and a few of the actors tried to restore calm. Memnon helped the eunuch to his feet. “Are you injured?”

“N-No … I am unhurt.” Hermeias held his arms aloft so the crowd could see him. “I am unhurt!” His scarred face was ashen, though, as he came forward and studied the dead man’s visage.

“Who was he?”

“One of Eubulus’s old partisans, I imagine, though I thought I had rid myself of the last of their kind.” The tyrant looked over at Memnon, who was wringing blood from his lacerated arm; a rush of concern replaced his pallor. “Come, my dear friend. That cut needs a doctor’s care. Kritias! Clear a path!”

Memnon lingered a moment over the corpse, wondering at his pawn’s name and if his kin were in the theater. Was he a truly martyr, or just a desperate cutthroat eager for gold and renown? No matter his motives, the courageous fool had done his duty.

I have Hermeias’s trust.

S

PRING CAME EARLY TO THE

T

ROAD.

T

WO MONTHS AFTER THE

L

ENAEA,

ships put to sea from Assos harbor, fat merchantmen shadowed by lean triremes, bound for Athens, for Pella, for Syracuse. Some would even brave the Persian-held waters off Cyprus for a chance to trade Greek wool and bronze for Egyptian linen and gold. For Memnon, though, the advent of spring heralded an end to his business with Hermeias.“It’s done,” the Rhodian said, bounding into the eunuch’s sun-drenched study without waiting to be announced. “Mentor has agreed to meet you.”

Hermeias put his stylus down and leaned back in his chair, stroking his chin with ink-stained fingers. “When?”

“Midmonth, at my estate near Adramyttium. He’s troubled by the rumblings of open war between Athens and Philip, and is eager to secure allies of his own.”

“Why does he not come here?”

“For the same reasons you do not go to Sardis,” Memnon said, smiling. “You’re both afraid of treachery from the other. Adramyttium is a neutral place. My estate is out of the way, secluded, so you both can let your guard down and talk like men. His terms are not unlike those of a parley. Ten men apiece—though he’ll only have nine, as I will be his tenth—and the setting will be a fine Attic

symposium,

as befits gentlemen of your respective ranks. I will send ahead and have everything ready.”Hermeias looked askance at the Rhodian. “I had no idea you owned an estate near Adramyttium.”

“It was a gift from Artabazus, for when I become too old and gray to follow where Glory leads,” Memnon replied, not bothering to mention that he had only seen the estate once, and from afar. “But what’s this? I hear reluctance in your voice now. Have you changed your mind about the meeting?”

“No,” Hermeias said, concern knitting his brow. “Of course not. I am … since the incident at the theater I am leery of entering a place not under my complete control. I am sure, though, that all is as you say.”

“I can vouch for the setting,” Memnon said. He sat on a divan near the eunuch’s desk, any consternation over the unraveling of his plans well hidden. “As for the rest, you will have ten handpicked guards plus me as a hostage. Even if it were Mentor’s intent to seize you, for whatever reason, he wouldn’t lift so much as a finger so long as I’m under your power.” The Rhodian grinned. “I’m excellent insurance, if nothing else.”

Hermeias rose and paced the study. “You are no hostage, my friend, and you are much more than mere insurance. I trust your judgment on these matters.” The eunuch smiled suddenly. “A

symposium,

eh? Perhaps I should pare my guards down to seven and invite a trio of learned friends? Trustworthy men, of course.”“A fine idea,” Memnon said, relief flooding his limbs.

And so it was decided. In the second week of Mounichion, the Troad’s eunuch king left Assos by ship in the company of a contingent of his Guard, three sophists from Aristotle’s old school at Mytilene on Lesbos, and Memnon. Bearing east, their galley hugged the coast of the Bay of Adramyttium and reached the town that lent its name to the Bay on the morning of the second day.

Adramyttium was a small hamlet, rustic compared to Assos, its beaches and roadsteads dotted with fishing boats. Homes of old timber and dun-colored brick topped a low hill, along with ruined walls that spoke of a time of greater prosperity. Gulls hovered over fishermen’s shacks, alighting on drying racks or canting beams, ever watchful for a free meal. Naked children made a game of scaring them off.

The galley beached and the party disembarked. Memnon had arranged their transportation weeks in advance—a carriage for Hermeias and his sophists, a wagon for their luggage, and horses for the rest. The Rhodian assigned one guardsman to drive the carriage; another, the wagon. Kritias and the other four were unaccustomed to traveling on horseback, so it took Memnon the better part of the morning to get them where they could sit astride the shaggy ponies without falling off. Finally, near noon, under a cloudless blue sky, the cortege set out for the estate.

Hermeias looked uneasy. “How far is it, again?”

“Less than an hour to the south of town,” Memnon replied. He rode beside the carriage, unarmed and unarmored, looking like a country squire out for a leisurely ride. His calm manner assuaged the eunuch’s nerves so that before a mile had passed the carriage was alive with dueling dialectics.

They arrived at the estate without fanfare, clattering over a small wooden bridge and passing between a pair of stone pillars. A grove of oaks shaded the main house. As he rode closer, Memnon could not keep a smile off his face. During his sojourn at Assos, Artabazus’s workmen had kept themselves busy transforming the old house with its peeling whitewash into a stonewalled villa with windows covered by fretted screens and a roof of red Pactolus tile. Silver chimes tinkled in the warm breeze.

The carriage drew up out front and the guardsmen dismounted. Kritias, his hand on his sword hilt, studied the portico, with its red-daubed columns and bronze-studded doors flanked by young potted poplars. Memnon knew the guard captain felt the same sensation he did—the tangible force of invisible scrutiny. The Rhodian, though, knew its source.

“Be at ease,” Memnon said, clapping Kritias on the shoulder as he bounded onto the portico.

Hermeias clambered down from the carriage. “Are we the first to arrive, I wonder?” he said. “Still, though I had hoped your brother would meet us, by arriving ahead of him we have an excellent opportunity to survey the lay of the land, as they say. I am eager—”

“Mentor’s not here,” Memnon said, his manner suddenly brusque. When he turned to face the eunuch, the composure he’d maintained since arriving at Assos was gone, replaced by cold rage. “Nor does he plan on coming. He wants you brought to him at Sardis. In chains, if need be.”

Hermeias recoiled, stricken. “What? What are you saying?” “You men!” Memnon gestured to the milling guardsmen. “If you value your lives, do not move! You’ve been easy prey, Hermeias. Far easier than I would have believed for a man of your reputation. You should be flattered that your enemies hold you in such high regard.”

“Black-hearted bastard!” Kritias snarled. He jerked his sword free and took a step toward Memnon. “Protect the—”

An arrow loosed from high among the oak leaves struck Kritias in the back of the neck, shattering his vertebrae. The guard captain pitched forward, dead before he hit the ground. His sword skittered across the portico. Memnon stooped and retrieved the weapon. To the other guardsmen, who looked on the verge of action, he said, “Move and you die! Understood?”

Behind Memnon, the villa doors crashed opened and a dozen soldiers emerged, spear-bearing

kardakes

in scaled Median jackets and peaked helmets, commanded by Omares, Artabazus’s old partisan, his hair and beard as long as a Spartan’s and shot through with gray. Under his direction, the

kardakes

divested the eunuch’s men of their weapons and herded them into a knot. A handful of green-and-brown-clad archers dropped from the oak trees; from the rear of the house more soldiers came and led the horses away. All the while, Hermeias spluttered and cursed.“You foul betrayer!” the eunuch screeched. He might have leapt at Memnon had his fellow sophists not restrained him. “I trusted you! I trusted you and this is how you repay my hospitality?”

Memnon’s smile lacked any vestige of humor. “You trusted me because of what I could offer you, not out of some poetic gesture of guest-friendship. You wanted access to my brother. For all your insufferable posturing about the merits of philosophy, you are no different from a common tyrant. At least Eubulus was honest.”

“Strike me down, then!” The eunuch shrugged off his companions and stepped closer to Memnon. “Strike me down if you style yourself a tyrannicide, and avenge your dear Eubulus! I will die for my philosophy, dog!”

“Indeed, and you likely will, but not today. Nor should you delude yourself into thinking this has anything to do with your former master, though one could argue that you authored your own doom with his murder. With Eubulus alive, Artabazus would have retreated to Assos instead of seeking asylum at Philip’s court.” Memnon descended from the portico. He towered over the eunuch as he grasped his right hand, tugging his signet ring off. “Bind them,” he said to Omares.

Quickly, Hermeias and his sophists had their hands lashed together with leather cords. The unlucky philosophers were separated from their patron and put with the guardsmen—who, at a gesture from Memnon, were led to the rear of the villa while a pair of

kardakes

removed Kritias’s body. “See he receives a proper burial,” Memnon said. “For all his misplaced loyalty, he was a good man.” In a moment, Memnon and Omares were alone with Hermeias.The Rhodian sat on the portico steps and stared at the sardonyx signet. “An interesting place, Philip’s court,” he continued. “That’s where I happened across your old crony, Demokedes. Honestly, I thought it nothing more than innocent coincidence until Philip installed your own son-in-law as young Alexander’s tutor. That’s when I decided you had become too much of a liability and would need to be removed. But how … how to prize you from this comfortable little nook you’ve created for yourself without sparking rebellion in all the cities that pay you homage?”

Hermeias gave a triumphant bark. “The sting of rebellion will be my legacy to you! My people will never stand for Persian autocracy! When they hear of your foul treachery they will rise up! My people will avenge me!”

“Don’t waste your melodrama on me, eunuch. Wait until you have an audience who might appreciate it,” Memnon said. The signet ring glittered in his fist. “These people you so fervently believe in … they are staunch partisans? Followers of the king’s law?”

“To the death!”

Memnon laughed, tossing the ring in the air and catching it. “Omares, fetch me something to write on! The king of the Troad is about to draft a letter to his loyal, law-abiding followers!”

17E

DICTS CIRCULATED THROUGH THE AGORAS AND COUNCIL HALLS

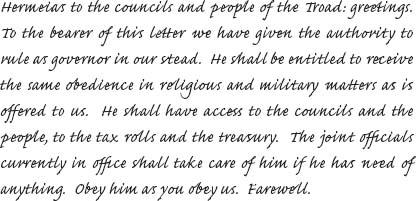

of the Troad; in steep Assos; in Atarneus, with its impregnable walls; in Antandrus, on the slopes of Mount Ida; in hallowed Troy and the towns of the Skamandros Valley; in Sigeum, on its windswept headland; and in Abydus, on the Straits. With exceptional gravity, heralds read aloud the wishes of their king:

Those who doubted the edict’s veracity had but to glance at the impression in the wax seal to have those doubts allayed. Clearly they could see the image of Athena in her guise as the goddess of wisdom, an owl perched on her upraised palm.

It was Hermeias’s seal …

O

N MIDSUMMER’S DAY

, M

EMNON RETURNED TO

S

ARDIS.

H

E RODE AT THE

head of a column of soldiers, mounted

kardakes

whose long spears bore fluttering pennons of purple and gold. Wagons trundled behind them and in their wake shuffled a line of dusty prisoners chained together at the neck. Word of the Rhodian’s arrival fired the city’s curiosity; commoners lined the road to the fortress, jostling for a chance to view the procession as it passed. Courtiers and functionaries watched from the battlements as Memnon’s troops rode through the fortress gates, whips cracking over the bowed backs of the prisoners.Mentor, attended by Spithridates and Rhosaces, awaited him at the head of the monumental staircase leading to the palace’s columned portico. A thousand eyes watched as Memnon dismounted, his blue linen cloak settling around his armored shoulders. A thousand ears heard the scuff of his cavalry sandals as he ascended the stairs, shadowed by two soldiers carrying a bronze-bound chest. The Rhodian stopped at a respectful distance and made his obeisance to the satraps, straightened and, in a clear and commanding voice, said, “Brother, I bring you tokens from the people of the Troad!” At his gesture, the two soldiers brought the chest forward, placed it at Mentor’s feet, and retreated. Memnon knelt; he unfastened the hasps and threw the lid back, revealing a pair of terracotta jars. “Earth and water, symbols of their submission!”

The pronouncement caused a furor among the courtiers, a buzz of disbelief. “All of the Troad?” Rhosaces of Ionia said, giving voice to the crowd’s skepticism that anyone could bring the region to heel in so short a time. Younger than his brother Spithridates, Rhosaces had a lean face dominated by a hooked beak of a nose and a bristling black beard.

“All of it!” Memnon’s nostrils flared. “And since I knew there would be those among you who would doubt my accomplishment, I’ve brought a witness!” Another gesture produced a rattle of chains as Omares led one of the prisoners up the stairs, thrusting him onto his belly at the satraps’ feet. Dirty and disheveled, clad in the remnants of royal finery, the prisoner struggled against the pressure of Omares’ foot on his back.

“Who is this creature?” Spithridates said, his nose wrinkling.

“Surely you recognize him, this man who once made you a gift of three

talents

of unrefined gold from Mount Ida to insure his ships would be welcome in your brother’s Ionian ports?” That was a rumor learned from his cousin, Aristonymus; for it to cause the Persian brothers to exchange troubled glances only confirmed Memnon’s suspicions that neither man could be trusted. With a flourish, he said, “Here is the eunuch, Hermeias, who once ruled the Troad, stripped of his office and his dignity! I present him to you, my brother, as proof of my success!”“Foul traitors!” The eunuch spat at Mentor’s sandals. “May you drown in the cursed Styx!”

A slow smile spread across Mentor’s face. “Proof, indeed. You’ve done well, Memnon. I accept the Troad’s submission! Take this wretch away. We will speak soon, Hermeias—soon and to agonizing lengths.”

Omares removed his foot from the eunuch’s back and manhandled him to his feet. Chains clashed as two of Mentor’s men seized the prisoner. Hermeias, though, wrenched himself free of their grasp; he drew himself up to his full height. “I will walk to my doom!” he said.

Here’s the audience he hoped for,

Memnon thought,

the chance to carve his own epitaph.

He did not disappoint. “Tell my friends I have done nothing base, or unworthy of our master’s teachings!”“Ever the philosopher,” Memnon murmured as the eunuch strode off like an honored guest rather than a prisoner under escort. Mentor, though, immediately dismissed the captive from his mind; the elder Rhodian grinned at Omares, who returned the gesture.

“You old dog!” Mentor said. “I knew he’d embroil you in this!”

“It was my pleasure, sir.”

“ ‘Sir,’ is it? Zeus Savior and Helios! Aren’t you the proper one, now? What have you done to him, Memnon?”

“It must be the immensity of your august presence,” he replied.

With the formalities at an end the onlookers drifted away, returning to whatever business brought them to the palace in the first place. Some were petitioners seeking a moment of the satraps’ time; others simply attended court day after day in hopes of securing their lords’ favor. Memnon saw visitors from the Royal Court at Babylon, envoys from the Aegean cities, Phoenicians and mainland Greeks, all haggling with the chamberlains for Mentor’s attention.

Little wonder he’s looking even thinner and as pale as a shroud,

Memnon thought as he signaled for his officers at the base of the stairs to dismiss the

kardakes.

A groom led his and Omares’ horses off to the stables.“Come.” The elder Rhodian turned and made his way across the broad portico to the Apadana. Heavy doors stood wide-open all around, allowing cool incense-laden air to flow without obstruction between the myriad columns. “How many men did this venture cost me?”

It took a moment for Memnon’s eyes to adjust to the gloom after the brilliant sunshine on the portico. “None,” he replied, his words amplified by the cavernous chamber. “We didn’t lose a man.”

Upon overhearing this, Spithridates, who had preceded them with Rhosaces, stopped and spun around. “Impossible! You cannot pacify a region of that size without casualties!”

“I am no liar, my friend,” Memnon said, a dangerous edge to his voice. “And you’d do well to remember that. We suffered no casualties.”

Mentor frowned. “How not?”

“I used a weapon they weren’t expecting.” From beneath his armor, Memnon drew out a silver chain; Hermeias’s signet ring dangled from it. He held it aloft for the others to see. “A weapon borrowed from our own Great King’s arsenal. You see, I sent letters to the city councils and officials.”

“Letters?” Spithridates sneered. “Preposterous!” Beside him, Rhosaces laughed aloud.

“Don’t scoff, my lords,” Omares said. “It was the damnedest bit of sleight of hand I’ve ever seen.”

Mentor silenced them with a look. “You sent … letters?”

“Yes. Letters of abdication, sealed with the eunuch’s own emblem. Hermeias’s partisans decided he’d gone off on some half-baked philosophical crusade, but they acceded to his wishes and confirmed the letter-bearers, all allied Greeks of my own choosing, as governors of their respective

poleis.

All that remained was to root out the malcontents.”Mentor’s rumbling laughter degenerated into a fit of coughing. He held up his hand, forestalling his brother’s concern. “Zeus Savior!” he wheezed, catching his breath. “Thank the benevolent gods you’re on our side!”

Both Persians, though, sniffed in disdain. “No matter how cunning,” Spithridates said, “artifice is a poor substitute for valor.” With that the satraps turned and retreated deeper into the Apadana, their retinues cleaving to them like toddlers to their mother’s skirts.

“Brother,” Memnon said in a low voice. “If it’s in your power to strip them of their rank and send them from you, do so. They mean you harm. I can feel it.”

“Me? I’m but a stumbling block to their ambitions, an annoyance at best. It’s you they should fear.” Mentor draped an arm around his brother’s shoulder. “Still, if it is harm they’re hatching, I trust you will avenge me with more than a letter. Come on, Omares! We need wine! Wine to celebrate both Memnon’s triumph and your sudden rise to respectability!”

I

T WAS NEAR DUSK BEFORE

M

EMNON COULD SLIP AWAY FROM HIS BROTHER’S

impromptu drinking party, leaving the elder Rhodian and Omares deep in their cups, singing off-key hymns to Dionysus. Nor were they alone in their revelry. Guests from the Asian Greek lands happily joined in, along with a handful of adventurous Persians who saw great wisdom in their ancestors’ admonition to debate serious matters first drunk, then sober. Mentor, however, sent their debate spiraling into oblivion by insisting they switch to undiluted wine.Sounds of their merriment faded as Memnon retreated into the heart of the palace. He had missed seeing Khafre and Pharnabazus; a chamberlain reported they were both at Ephesus—Khafre to replenish his store of medicines and Pharnabazus as Mentor’s liaison to the shiploads of mercenaries Thymondas had sent over from the Greek mainland—and were due to return soon. The rest of the family had gone with Artabazus to the Great King’s court at Babylon.

Memnon’s rooms, in a wing of the palace reserved for royal kin, once belonged to Croesus’s beloved son, Atys, slain hunting wild boars in Mysia “to punish his father’s

hybris

,” according to Herodotus. Polished bronze lamps illuminated a wall-sized painting depicting the young man’s death: his body sprawled in the heather, encircled by his weeping comrades, with his gory head cradled in Croesus’s lap. The old king’s tragedy became the room’s theme. Antique iron boar-spears hung above the cold hearth and inlays of yellowed tusk-ivory decorated the woodwork—chairs, table, and bed.Slaves had delivered Memnon’s belongings from the wagons; servants had put everything in its place, hanging his weapons and shield near the door and erecting two stands for armor. One held his bronze breastplate and greaves, the other his lighter linen cuirass. His helmet, with its tall crest of blue-dyed horsehair, rested on the shoulders of his

lineothorax.

His traveling chest of cypress-wood, its patina worn with age and scarred from indelicate handling, lay at the foot of the bed, while a wicker-and-leather scroll basket, filled with volumes appropriated from Hermeias’s library, sat atop the table. Memnon caught this up by its carrying strap and headed back out the door.The women’s quarters lay at the end of a long hallway, behind a door guarded by silver-haired

kardakes,

veterans who had served Artabazus’s cause in their youth. They smiled and clapped Memnon on the shoulder as he passed into the antechamber. Inside, the Chief Eunuch of the harem held court. He was a balding and fussy little man, his potbelly straining against the multicolored linen of his robes. A lesser eunuch fanned him while a pair of Barsine’s maids—who should have been attending to their mistress—massaged warm, herb-laced oil onto his swollen ankles.Memnon glared at him as he crossed the antechamber to Barsine’s door.