Men of Bronze: Hoplite Warfare in Ancient Greece (52 page)

Read Men of Bronze: Hoplite Warfare in Ancient Greece Online

Authors: Donald Kagan,Gregory F. Viggiano

Boeotia

The major, and pioneering, survey project carried out across the rural territories of the cities of Boeotia between 1978 and 1991 is still not fully published, although many important and full publications have appeared. Overall, it is clear that the Geometric occupation was largely restricted to a few key settlements that later became urban sites (Bintliff 1999: 15–18). The sixth century (Late Archaic) appears to be the period when urban sites acquired walls, and a limited amount of activity, possibly dispersed farmsteads in some cases (see below), first appears in the rural territories of these cities (Bintliff 1999: 19). The peak of rural sites (and populations) comes in the fourth century BCE (Bintliff 1999: 23), with a fairly dramatic shrinkage from around 200 BCE (Bintliff 1999: 27). However, it is clear that in the Classical period the distribution of different types and sizes of rural sites (e.g., hamlets/large farm, small isolated farmsteads) varies considerably from one part of Boeotian territory to another (Bintliff et al. 2007: 146–47).

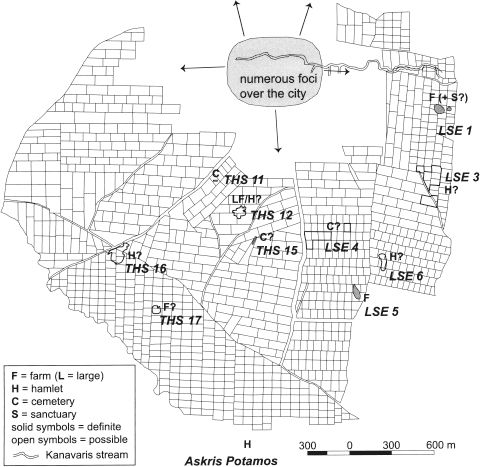

The area south of Thespiai has recently been published in more detail (Bintliff et al. 2007). Between the Late Bronze Age and the Late Geometric period there is almost no evidence of rural settlement, and the earliest documented rural activity is Late Geometric (Bintliff et al. 2007: 173). Geometric-Archaic settlement was largely focused on the center of Thespiai. Ten sites in the southern approaches to the city belonging somewhere in this period are mapped (Bintliff et al. 2007: 132, fig. 9.3) (

fig. 10-2

). Most of these appear to be hamlets with the occasional sanctuary or cemetery site (Bintliff et al 2007: 131–32, 172–73), but the actual ceramic evidence on which this map is based appears very thin when scrutinized in more depth. From the data helpfully published with the report, it is clear that there is almost no certain Geometric pottery and there are very few certain Archaic sherds per site; of the closely datable material most appears to be sixth century BCE (

table 10-2

). This contrasts dramatically with the very large numbers of Classical–Hellenistic sherds recovered.

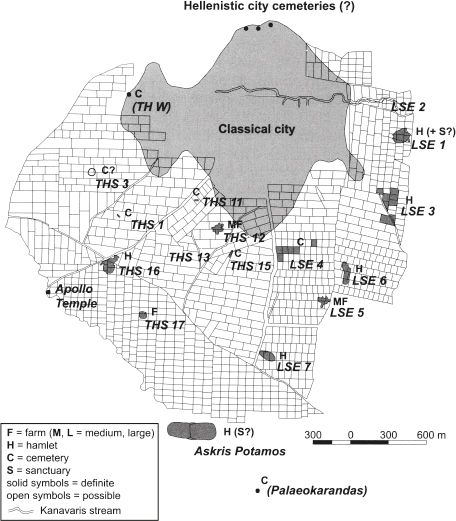

For the Classical period, the authors argue for several “bands” of occupation: a zone of cemeteries on the city’s edge, then a band of large estates or hamlets, then farthest out an area occupied by a few small scattered farms (

fig. 10-3

). This pattern seems to begin in the Late Archaic period (sixth century BCE) (Bintliff et al. 2007: 132). The cemetery zone appears to be an agglomeration of small family grave plots, not big civic cemeteries (Bintliff et al. 2007: 134). In the next band, the sites are all relatively large and thus seem most likely to be either the headquarters of large, wealthy estates or hamlets with several farming families occupying them. All these sites have easy access to (and from) the city. They are also close to good agricultural land, which, judging from the very heavy background scatter, was extremely intensively exploited in Classical times. The third, outermost group consists of only two examples in this sector of the Boeotian landscape, but other areas in Boeotia Survey territory show many more of these small rural “farmstead” sites (Bintliff et al. 2007: 135–36).

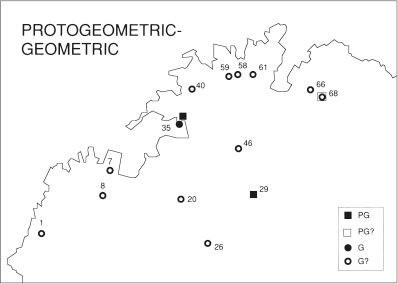

Keos

The Keos Survey was carried out in the 1980s in northwest Keos, mostly in what would have been the territory of the Classical city of Koressos, though the eastern sector of

the survey area would almost certainly have fallen within the territory of Ioulis. Also included within the survey area was the important prehistoric site of Aghia Irini (Cherry et al. 1991: 5–6). The only significant amount of Protogeometric and Geometric material came from the excavations at Agia Irini where a sanctuary of this period was built over the Bronze Age sanctuary. Few sherds can be dated earlier than the Archaic period (Cherry et al. 1991: 329). Only one single certain Protogeometric (tenth century BCE) sherd was found in the countryside at site 29. All sherds identified as “Geometric” (ninth–eighth century BCE) in the survey, and they are few, are possible but not definite. There is little evidence for any Geometric presence at the polis site of Koressos from either survey or excavation (Cherry et al. 1991: 332) (

fig. 10-4

).

FIGURE 10-2. Thespiai, southern approaches, Geometric-Archaic sites (Bintliff et al. 2007: 132, fig. 9.3). Courtesy of John Bintliff.

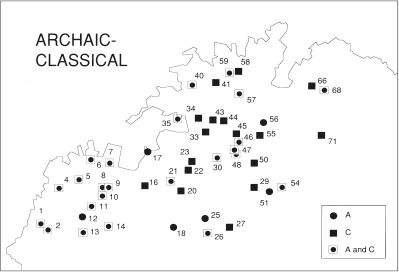

The Archaic period sees a significant increase in activity both in the countryside and at the polis center of Koressos (

fig. 10-5

). However, almost all the Archaic pottery discovered is later than the seventh century BCE (Cherry et al. 1991: 330), and the great majority of Archaic sherds that can be identified with certainty date to the sixth century (Cherry et al. 1991: 33l, fig. 17.2). It is clear that the overall amount of

deposition of sherd material was greater in the Archaic through Hellenistic period than in the Roman period (Cherry et al. 1991: 329). Indeed, the bulk of sherd deposition appears to belong to the Classical–earlier Hellenistic (down to the third century BCE) phase (Cherry et al. 1991: 330–31). However, the Keos authors explain particularly clearly and straightforwardly just how few sherds can be pinned down in date to a precise time period (see above, Cherry et al. 1991: 328–31). There were fewer certain fifth-century BCE sherds than sixth-century sherds, but the sherd total for the fifth century is much higher if the possible fifth century sherds are included (Cherry et al. 1991: 330–31 and fig. 17.2). There is a significant decrease in the number of diagnostic sherds in the fourth and third centuries BCE (Cherry et al. 1991: 331, fig 17.2), and little diagnostic material postdating the third century was found until Late Roman times (Cherry et al. 1991: 330).

TABLE 10-2

Finds from the sites identified as Geometric and Archaic in the southern approaches to Thespiai (derived from data in Bintliff et al. 2007)

Site | Ceramic finds | Comments |

THS11 | 2A in survey | Small cemetery site ca. 200 m from edge of Classical city. 1981 excavation revealed Late Archaic and Late Classical tombs constructed in two separate phases of use (Bintliff et al. 2007: 69–70). |

THS12 | no certain G or A | “Settlement before the end of the archaic period remains a possibility only” (Bintliff et al. 2007: 73). |

THS15 | 1 possible A, no definite | “Its use may just possibly have begun in Late Archaic times” (Bintliff et al. 2007: 79). |

THS16 | 1 G?-A | “May conceivably have originated before the end of the Archaic period” (Bintliff et al. 2007: 81). |

THS17 | 2 possible A | “‘Possibly beginning in the Archaic period” (Bintliff et al. 2007: 83). |

LSE1 | 1 G-A; 1 probable G-A; 1 certain A; 6 probable A; 6 possible A; 1 M/L Corinthian-6th c.; 2 Late A/Early C; 1 6th–5th c. | Interpreted as a sanctuary in this period (Bintliff et al. 2007: 44). |

LSE31 | aryballos mouth c. 600; 2 A; 6 probable A | Hamlet site that was perhaps already large in the Archaic period (Bintliff et al. 2007: 49). |

LSE4 | 8 Late A ca. 500 BC; 2 A; 1 Late A-C; 12 probable A | Interpreted as Classical period burial site (Bintliff et al. 2007: 52). |

LSE5 | 1 A; 1 probable G-A; 7 probable A; 1 probable 6th c. | “Seems likely that main settlement begins during the Archaic period” (Bintliff et al. 2007: 54). |

| LSE6 | 2 G-A; 6 A; 2 probable A; 2 possible A | “Occupation of site must begin at this time [G-A and A]” (Bintliff et al. 2007: 55). |

FIGURE 10-3. Thespiai, southern approaches, Classical-Hellenistic sites (Bintliff et al. 2007: 133, fig. 9.4). Courtesy of John Bintliff.

In summary, most of the sites discovered in the countryside appear to have been isolated “farmsteads.” They date mostly to the later Archaic (probably mostly sixth century BCE) and Classical periods, and the numbers decline in the Hellenistic period. Such sites do not appear to have been a feature of this part of the Kean country side before the seventh–sixth century BCE. (Cherry et al. 1991: 336–37).

Southern Argolid

The Southern Argolid Survey was carried out during the 1980s in the southernmost part of the Argolic Peninsula, in the area that would probably have been the rural territory of the Classical cities of Hermion and Halieis, which also included the important prehistoric site of the Franchthi Cave (Jameson et al. 1994: 29–48 and 25, fig. 1.7).

After a rich Late Helladic record (Jameson et al. 1994: 236, fig. 4.16) very little early Iron Age (1000–700 BCE) material was found. Only one site with a Protogeomet-ric (1000–900 BCE) component was discovered (Jameson et al. 1994: 236, fig. 4.17, 372), and the same site also has an Early Geometric (900–850 BCE) presence, but of uncertain date (Jameson et al. 1994: 237, fig. 4.18). There are three uncertain and three

certain Middle Geometric (850–750 BCE) sites (Jameson et al. 1994: 236, fig. 4.19). Up to twenty-two sites have Late Geometric (750–700/675 BCE) pottery, but many are uncertain in terms of date and site size (Jameson et al. 1994: 238, fig. 4.20). The real boom in rural sites appears in the later Archaic (700/675–480 BCE) and Classical periods (480–338 BCE; forty-two sites documented) and even more in the Late Classical/Early Hellenistic period (350–250 BCE; seventy-five sites): the latter period is defined as a discrete phase in the Southern Argolid Survey (Jameson et al. 1994: 238, fig. 4.21; 239, figs. 4.22 and 4.23; 253, table 4.7). Site numbers decline in the later Hellenistic (250–50 BCE) period.

FIGURE 10-4. Keos Survey, Protogeometric-Geometric sites; no. 35 is Aghia Irini (Cherry et al. 1991: 333, fig. 17.5). Courtesy of John Cherry, Jack Davis, and the Cotsen Institute.

FIGURE 10-5. Keos Survey, Archaic-Classical sites; no. 7 is Koressos, the polis site (Cherry et al. 1991: 334, fig. 17.6). Courtesy of John Cherry, Jack Davis, and the Cotsen Institute.