Mermaid in Chelsea Creek (31 page)

Read Mermaid in Chelsea Creek Online

Authors: Michelle Tea

“What would I do?” Sophie flared. “I'd fight Kishka! I wouldn't let her take my sister! I'd do anything! Anything I could, I'd make the biggest zagavoryâ”

“Sophie, Andrea not have magic. Andrea have nothing. Kishka hurt Andrea Andrea's whole life. Andrea, she was defenseless.”

It could have been me

, Sophie thought. Her mother just as easily would have let Kishka spirit her away, gone. Sophie felt cold at the thought, cold and small. She turned on Hennie.

“You let her?” she accused. “You had a part in this! You let Kishka take my sister!”

Hennie nodded, crying freely now. “Yes I did, child. It is what was meant to happen. One of you would go. One would stay. I did like Boginki, I make switch. So that you stay free. So that you grow powerful to do what you are meant to do.”

“What am I meant to do, Hennie?”

“All the sadness upon the humans is like a deep spell from the bad, the source Kishka takes her power from. Over time it grow and grow and grow, you know. Humans not used to be so sad. Everyone on the sad pills or happy pills. Everyone scared inside and no one know why. People fighting, people so mean, not used to be so. You will take it all, child. You will take it all out of everyone. You will make the world so different it will be as if you had recreated it.”

“Me?” Sophie was sickened with dread.

“Yes. There will be others, other girls. You will have help.”

“Where are they?”

“You will find each other when time is right. You are all growing, all training, all magic. Part human, so you can feel the zagavory of sadness yourself, it is in your heart. But magic, too. Magic you can find it and take it away.”

“Hennie,” Sophie said. “Where is my sister?”

“She is with Kishka.”

Sophie remembered the plants, the wall of plants in the trailer, a fortress of greenery. The tiny hello.

“In Kishka's trailer,” Sophie said. “In the plants.”

“Yes, child.”

“Right there. She's just right there, right here in Chelsea, at the dump, and no one is helping her?”

“Sophia, the plants. They are so poison. Kishka raise her inside a poison garden, now the only air she know is air of poison flowers. Her air would kill anyone. She live inside it since two, three days old. She maybe poison now, herself.”

“It wouldn't kill me,” Sophie asserted, though she remembered the dizzying affect of being so close to the plants, the way her breath had turned leaden in her lungs. “I could do a zagavory, so could youâ weâcould take herâ”

“Take her where, Sophie? She does not breathe air like we do. She cannot leave the plants. Our clean, healthy air is poison to her. She would die, love. And we would sicken from her closeness. She is a poison flower.”

Sophie cried tears of frustration. “There's nothing we can do?” she wailed. “I'm able to save the world and swim with mermaids and talk to pigeons but I can't rescue my own sister?”

“Just because many things are possible does not mean all is possible, Sophie.”

“She has no name,” Sophie said.

“No one has named her. She is like, little flower creature. Like little animal girl.”

“Is she⦠happy?”

“I do not know.”

“Go inside her! See if she's happy!”

Hennie held a hand up in front of her. “No more go inside that child. That a promise I make to the good.”

“Well I will, then.”

“That fine, Sophie. You do as you will. But I ask you, you must focus on what is your duty here. It is bigger than you, than your sister, than me. You must not be distracted by this, this tragedy.”

“Why did Kishka even want her?”

“Kishka for bad. She enjoy humans being sad, being angry. Sad people easy to control, yah? She have power, it feel good to her. She make many people do her will. She want to make sure no good magic girl come and mess it up for her. So she make this flower jail.”

“Why is she controlling people, does she take their money?”

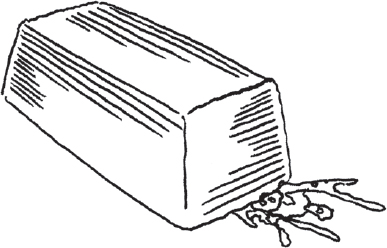

“Earthly wealth means nothing, any OdmieÅce can make wealth, hereâ” Without even sounding her zawolanie, Hennie produced a giant bar of gold. She placed it on the table with a

thunk

, smooshing a stray grape.

“Oh my god,” Sophie breathed. “That's real? It's not, like, counterfeit?”

“Is real,” Hennie said.

“Could I do that? Could I make, like dollars, like a big wad of cash?”

“You do what you like, sure. Is not point of your power. Do as have to do. My point is, Kishka have such things, yah. Have own cave in Poland, full with jewels, with gold, what you say, wads of cash. Such things, who cares? You live so long with such power, you stop to care. But, Kishka care. Gives her much power over humans.”

Sophie didn't know what felt more unreal, that her grandmother was a gazillionaire, or that she had the power to make

herself

a gazillionaire. Sophie had often daydreamed that maybe she was really the child of some

other

family, one with money, money like a key to unlock the door to the world. Sophie could go to school, travel, eat delicious food. Now she had the means to such a life, but it didn't seem like such a life was available to her.

When all this is over, I'm going to boarding school

, Sophie decided.

“Does Kishka know?” Sophie asked. “Does she know she has the wrong girl?”

“Yah.” Hennie nodded. “Yah, I think she is figuring it out.”

“Why is she so stupid?” Sophie asked snarkily. “How come she couldn't figure that out if she's such a big deal?”

“Kishka not stupid,” Hennie warned. “Do not endanger yourself to think that. Witches powerful, but imperfect. All beings imperfect, all creatures. Only the good is perfect, perfect good. And the bad, too. The

bad is perfect bad.” Hennie sighed. “You could be Harvard professor now, child. You be philosopher. I know this all confusing for a small girl.”

“I'm not small,” Sophie challenged. Though she had felt tiny only moments ago, her anger, this injustice, it had filled her heart. She felt giant with feeling and with purpose.

“No, dear,” Hennie agreed. “You not so very small. Your heart very, very big. You must care for it, keep pure. You must eat much salt. You go with Syrena, the mermaid, she live in the salt, she teach you very much.”

“So, I guess I'm not going to high school,” Sophie said.

“Oh, no, child. You will have to go to high school! Cannot beâ what you sayâdrop-out! You spend summer with Syrena, you come back for school.”

“Hennie,” Sophie said. “That is the most ridiculous thing I have ever heard.”

“No worry now,” Hennie brushed the topic away. “You go, do what you must do right now.”

“Can I take this?” Sophie's eyes had continued to catch on the gleaming bar of gold on the wooden table. It looked like a candy bar made to

look

like gold, a fat bar of chocolate wrapped in foil. “I want to give it to my mom.”

“I think that would be fine.” Hennie nodded. Sophie picked up the thing, which weighed as much as she thought it would, and slipped it into her magic pouch. The bag sagged with its heft.

“Okay, then,” Sophie said.

Beside them, on the straw mattress, Laurie LeClair twitched in her sleep, coming awake slowly, then quickly. She felt the foreign room around her, the strange, rough bed she slept upon, and sat bolt upright, her eyes flashing like a cornered animal. Carl growled a low growl and moved closer to Hennie. Laurie looked the witch square in the face, her face alive with the absence of the Dola.

“Who the fuck are

you

?” she demanded, and Alize began to cry.

O

utside Hennie's, Sophie was greeted by the pigeons. They swooped down from the wire above, arranging themselves at Sophie's dusty feet. Roy spoke.

“We will escort you to the creek tonight,” he told her. “And we will escort you home now, but at a distance, for there are people around.” He looked nervously to Livia, who nodded warmly.

“Thank you, Roy,” she said. Roy, relieved to be free of his messenger duties, dashed into the sky, his wings aflutter with nervous energy.

“Wait,” Sophie said, something clicking. “Is Roy your son?”

Arthur stepped forward, his breast jutting out above his limping feet, bands of heather gray and charcoal ringing his throat like strands of kingly jewels, the whole feathered length of it gleaming green, then fuchsia. “Roy is our son.” He stretched his wing around Livia, who relaxed into the curve of it, exulting, for a moment, in being beloved.

“How great,” Sophie said, grinning at the little family, their pride and love and close work.

“He hatched a year ago this spring,” Livia said.

“Wow,” Sophie said. She looked at Livia and Arthur. “How old are you guys?”

“Birds,” Arthur corrected. “We're not guys, we're not humans. âHow old are you

birds

?' “

“Okay, so.” Sophie waited.

“We're five,” Livia said. “Arthur and I are five years old.”

How long do pigeons live for

? Sophie wanted to ask, but it was a rude question, a cruel question, and one that Sophie wasn't sure she wanted answered.

The birds took off above her, and Sophie shuffled down Heard Street, toward home. It was only three blocks away, and the blocks were not long, but they could feel interminable. Sophie's belly clenched with dread as she spied the familiar heap of dirt bikes laid out across the sidewalk, their nubby black tires spinning, the sun shooting like lightning off their silver spokes. Sophie tried walking past the house with her eyes cast down. Maybe if she ignored them the boys would ignore her or, even better, not see her at all. But this never worked; all it ever did was make her look scared. Sophie knew that she didn't have the luxury of being scared of anything anymore. She couldn't

afford to be scared of a bunch of stupid human boys when she was about to hop into the sea with a mermaid.

The taunts were a white noise of kissy squeaks and dog barks and facetious wolf-whistles. Sophie raised her head to face her harassers and found herself looking straight at Ella. Ella, with a cigarette in her hand, sitting on the lap of the smoking boy, who also held a cigarette in his hand. The two of them were encased in a fog of smoke, the boy's arm slung around Ella's middle, anchoring her to the slope of his lap. Ella looked away quickly. I

s she going to pretend she doesn't know me

? The boy she sat upon joined his friend in a braying howl, and Ella winced at how close the sound was to her ear.

Sophie stopped short before the mound of bikes, and took in the scene.

“That's the bitch who hissed at us!” the big one yelled, excited. “You gonna do that again? Hiss again, pussy!” The boys thought that was hilarious. Their guffaws filled the air, sounding to Sophie like donkeys, which made her think of Pinocchio, of so many fairy tales where boys were turned into animals. She could do that to them. She could make them a pack of mules, crammed onto a crumbling porch in Chelsea, looking ashamed, their long ears drooping. But Sophie thought of her grandfather. He didn't even know he was cursed, he was just a dog. Sophie wanted to hurt these boys. And Ella. She wanted to hurt Ella, too.