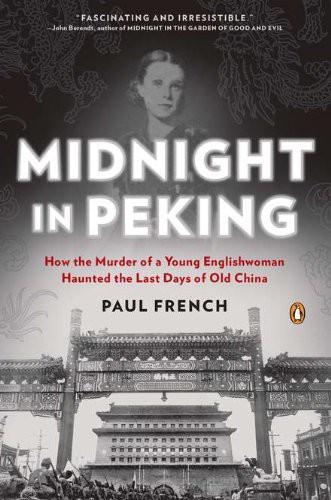

Midnight in Peking: How the Murder of a Young Englishwoman Haunted the Last Days of Old China

Authors: Paul French

Tags: #Mystery, #Non-Fiction, #History

PENGUIN BOOKS

Midnight in Peking

Historian Paul French lives in Shanghai, where he is an economist and analyst, frequently commenting on China for the English-speaking press around the world. The author of a number of books on China between the world wars, including

Carl Crow: A Tough Old China Hand

and

Through the Looking Glass: China’s Foreign Journalists from Opium Wars to Mao

, he studied history, economics and Mandarin at university and has an M.Phil. in economics from the University of Glasgow.

Midnight in Peking

How the Murder of a Young Englishwoman Haunted the Last Days of Old China

PAUL FRENCH

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi – 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices:

80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published in Australia by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Group (Australia) 2011

This revised edition published in Penguin Books 2012

Copyright © Paul French, 2011, 2012

All rights reserved

Map: National Library of Australia (MAP G7824.B4 1936)

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA

French, Paul, 1966–

Midnight in Peking : how the murder of a young Englishwoman haunted the last days of old China / Paul French.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-101-58038-7

1. Murder—China—Beijing—Case studies. 2. Beijing (China)— History—20th century. I. Title.

HV6535.C43F74 2012

364.152'3092—dc23 2012001874

No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author’s rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

For the innocent

For Pamela

The north wind came in the night, ice covers the waters:

Once our young sister has gone she will never return

—

TRADITIONAL SONG OF THE CANAL PEOPLE OF NORTHERN CHINACut is the branch that might have grown full straight

—

CHRISTOPHER MARLOWE

,

Doctor FaustusThe belief in a supernatural source of evil is not necessary; men alone are quite capable of every wickedness

—

JOSEPH CONRAD

,

Under Western Eyes

By day the fox spirits of Peking lie hidden and still. But at night they roam restlessly through the cemeteries and burial grounds of the long dead, exhuming bodies and balancing the skulls upon their heads. They must then bow reverentially to Tou Mu, the Goddess of the North Star, who controls the books of life and death that contain the ancient celestial mysteries of longevity and immortality. If the skulls do not topple and fall, then the fox spirits—or

huli jing

, —

—

will live for ten centuries and must seek victims to nourish themselves, replenishing their energy through trickery and connivance, preying upon innocent mortals. Having lured their chosen victims, they simply love them to death. They then strike their tails to the ground to produce fire and disappear, leaving only a corpse behind them . . .

The Approaching Storm

T

he eastern section of old Peking has been dominated since the fifteenth century by a looming watchtower, built as part of the Tartar Wall to protect the city from invaders. Known as the Fox Tower, it was believed to be haunted by fox spirits, a superstition that meant the place was deserted at night.

After dark the area became the preserve of thousands of bats, which lived in the eaves of the Fox Tower and flitted across the moonlight like giant shadows. The only other living presence was the wild dogs, whose howling kept the locals awake. On winter mornings the wind stung exposed hands and eyes, carrying dust from the nearby Gobi Desert. Few people ventured out early at this time of year, opting instead for the warmth of their beds.

But just before dawn on 8 January 1937, rickshaw pullers passing along the top of the Tartar Wall, which was wide enough to walk or cycle on, noticed lantern lights near the base of the Fox Tower, and indistinct figures moving about. With neither the time nor the inclination to stop, they went about their business, heads down, one foot in front of the other, avoiding the fox spirits.

When daylight broke on another freezing day, the tower was deserted once more. The colony of bats circled one last time before the creeping sun sent them back to their eaves. But in the icy wasteland between the road and the tower, the wild dogs—the

huang gou

—were prowling curiously, sniffing at something alongside a ditch.

It was the body of a young woman, lying at an odd angle and covered by a layer of frost. Her clothing was dishevelled, her body badly mutilated. On her wrist was an expensive watch that had stopped just after midnight.

It was the morning after the Russian Christmas, thirteen days after the Western Christmas by the old Julian calendar.

Peking at that time had a population of some one and a half million, of which only two thousand, perhaps three, were foreigners. They were a disparate group, ranging from stiff-backed consuls and their diplomatic staff to destitute White Russians. The latter, having fled their homeland to escape the Bolsheviks and revolution, were now officially stateless. In between were journalists, a few businessmen, some old China hands who’d lived in Peking since the days of the Qing dynasty and felt they could never leave. There was the odd world traveller taking a prolonged sojourn from a grand tour of the Orient, who’d come for a fortnight and lingered on for years, as well as refugees from the Great Depression in Europe and America, seeking opportunity and adventure. And there was no shortage of foreign criminals, dope fiends and prostitutes who’d somehow washed up in northern China.

Peking’s foreigners clustered in and around a small enclave known as the Legation Quarter, where the great powers of Europe, America and Japan had their embassies and consulates—institutions that were always referred to as legations. Just two square acres in size, the strictly demarcated Legation Quarter was guarded by imposing gates and armed sentries, with signs ordering rickshaw pullers to slow down for inspection as they passed through. Inside was a haven of Western architecture, commerce and entertainment—a profusion of clubs, hotels and bars that could just as easily have been in London, Paris or Washington.

Both the Chinese and foreigners of Peking had been living with chaos and uncertainty for a long time. Ever since the downfall of the Qing dynasty in 1911, the city had been at the mercy of one marauding warlord after another. Nominally China was ruled by the Kuomintang, or Nationalist Party, under the leadership of Chiang Kai-shek, but the government competed for power with the warlords and their private armies, who controlled swathes of territory as large as western Europe. Peking and most of northern China was a region in flux.

Between 1916 and 1928 alone, no fewer than seven warlord rulers came and went in Peking. On conquering the city, each sought to outdo the last, with more elaborate uniforms, more ermine and braid. All fancied themselves emperors, founders of new dynasties, and all commanded substantial private armies. One of them, Cao Kun, had bribed his way to supremacy, paying officials large amounts in stolen silver dollars, since no official in China at that time trusted paper money. Another, Feng Kuo-chang, had been a violin player in brothels before illegally declaring himself president of all China. They and their ilk terrorised the city as they bled it dry.

Peking was certainly a prize. It was China’s richest city after Shanghai and Tientsin. Unlike those two, however, Peking was not a treaty port—those places seized from the Qing dynasty by European powers in the nineteenth century. There foreigners governed themselves, and built trading empires backed by their own police forces, armies and navies. Peking was, at least for now, Chinese territory.

But it was no longer the capital, and had not been since 1927. In that year, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, unable to pacify the northern warlords and struggling to cement his fragile leadership of the Kuomintang, had moved the seat of government to Nanking, some seven hundred miles south. From there he launched the Northern Expedition, a military campaign that attempted to wipe out both the warlords and the nascent but troublesome Communist Party, and unite China under his rule. He was only partially successful. Peking was run by the Hopei-Chahar Political Council, led by General Sung Cheh-yuan, commander of the Kuomintang’s Twenty-Ninth Route Army. General Sung, who had a formidable reputation for soldiering, remained loyal to the Nanking government even after the arrival of a new player in the struggle to control China: Japan.

In 1931, under the guise of their long-dreamt-of Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, the Japanese invaded Manchuria, in China’s northeast. They then set about bolstering the region with troops in preparation for an advance south to capture the whole country. But there were constant skirmishes with Chinese peasants, who were resisting the theft of their lands. Even farther north, Japanese agents provocateurs were stirring up anti-Chinese feeling in Mongolia.

General Sung paid lip service to the Japanese while resisting their demands to cede the city, but his council was too weak and corrupt to stave off the encroachment of enemy troops. These steadily encircled Peking, and by the start of 1937 had established their base camp a matter of miles from the Forbidden City. Acts of provocation occurred daily, and the roads and train lines into and out of the city were disrupted. Japanese thugs for hire, known as

ronin,

openly brought opium and heroin into Peking through Manchuria. This was done with Tokyo’s connivance and was part of an effort to sap Peking’s will to fight. The

ronin

, their agents and Korean collaborators peddled the subsidized narcotics in Peking’s Badlands, a cluster of dive bars, brothels and opium dens a stone’s throw from the base of the foreign powers in the Legation Quarter.

Whatever the ferocity of the storm building outside—in Chinese Peking, in the Japanese-occupied north, across China and its 400 million people to the south—the privileged foreigners in the Legation Quarter sought to maintain their European face at all costs. Officially, Chinese could not take up residence in the Quarter, although in 1911 many rich eunuchs—former servants to the emperors and empresses who had been thrown out of the Forbidden City after the collapse of the Qing dynasty—had moved in. They were followed by warlords in the 1920s.

More than a few foreign residents of the Legation Quarter in its heyday described themselves as inmates, but if this gated and guarded section was indeed a cage, then it was a gilded one, with endless games of bridge to pass the time. Sandwiched between the legations were exclusive clubs, grand hotels and department stores. There was a French post office, and the great buildings of the Yokohama Specie Bank, the Banque de l’Indochine, the Russo-Asiatic Bank, and the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank.

It was Europe in miniature, with European road names and electric streetlights. St Michael’s Catholic Church dominated the corner of rue Marco Polo and Legation Street, and the latter was also home to the German hospital, where the nurses, Lazarene nuns, served

kaffee und kuchen

to their privileged patients. Residents of European-style apartment buildings went shopping at Kierulff’s general store, which sold perfume, canned foods and coffee. Sennet Frères had a reputation as the best jewelers in northern China, and Hartung’s was the leading photography studio and the first to have been established in Peking, while a Frenchman ran a bookshop and another a bakery. On Morrison Street (named after George Morrison—‘Morrison of Peking,’ the thundering voice of the

Times

of London in China) there was an English tailor and an Italian who sold wine and confectionery. White Russian beauticians staffed La Violette, the quarter’s premier beauty parlour. There was also a foreign police force, and garrisons for the five hundred or so foreign troops stationed in Peking.

Eight gateways, each with massive iron gates, marked the entrances to the Quarter and were manned by armed guards day and night. Chinese needed a special pass or a letter of introduction to enter this inner sanctum. Rickshaw pullers had their license numbers taken and had to leave immediately after they’d dropped off their fare. At the first sign of trouble in Chinese Peking, the gates to the Quarter were slammed shut—there would be no repeat of the deadly siege that had occurred during the Boxer uprising.

The memory of the Boxers still loomed large over the Legation Quarter. In 1900 the Society of the Righteous and Harmonious Fists, dubbed the Boxers, had swarmed down on the Quarter, intending to massacre all the

yang

guizi

—foreign devils—in the capital, and show that China could fight back against Western encroachment and gunships. They had already beheaded missionaries working in remote outposts, and as they approached Peking, their numbers swelled, thanks in part to the rumours that they possessed magical fighting skills, and that bullets could not harm them.

The Boxers held the foreign community under siege within the Legation Quarter for fifty-five days. They lit fires around the outskirts, fired cannons into the legations and tried to starve the inhabitants into submission. Eventually the siege was lifted by a joint force of eight foreign armies, including those of Britain, America and Japan. After liberating the Quarter, these troops went on a horrific looting spree, rampaging throughout the city, terrorizing all Peking. With seized Chinese money, the Quarter was rebuilt grander than ever and was now far better protected.

Whereas to most Chinese the Quarter was a second Forbidden City, to the foreigners living there in the 1930s it was a sanctuary, even if in their claustrophobic confines they sometimes felt, as one visiting journalist remarked, like ‘fish in an aquarium,’ going ‘round and round . . . serene and glassy-eyed.’

Rumour was the currency of the quarter. Conversations that started with who had the best chef and who was about to depart for home on a long-awaited furlough soon degenerated into who had commenced an affair with whom at the races, whose wife was a little too close to a guardsman at the legation. Sometimes darker things were hinted at, things beyond the normal indiscretions. Some people lost their moral compass in the East, or so the thinking went.

And there were plenty of places to spread rumours. The exclusive clubs and bars were hotbeds of intrigue and gossip. In the stuffy and very British Peking Club, it was black tie only. Whisky sodas were dispensed on trays by silent servants, the cacophony outside in Chinese Peking held at bay by windows covered with thick velvet curtains, and there were two-month-old copies of the

Times

and the

Pall Mall Gazette

on offer. In the swanky bar of the Grand Hôtel de Pékin, a respectable crowd sipped fancy drinks and twirled to an all-Italian band playing waltzes.

The more risqué Hôtel du Nord, on the edge of the Badlands, had a crowded bar that served draught beer, fashionable Horse’s Neck cocktails and dry gin martinis. Here the patrons were more rambunctious—the polite word was ‘mixed’—and they foxtrotted to jazz courtesy of a band of White Russians. And then there was the Grand Hôtel des Wagons Lits.

The Wagons Lits was a large, French-style hotel just inside the Quarter at the junction of Legation and Canal streets. Close to the city’s main railway station, it was a popular meeting spot. The bar was famous for its diplomatic clientele during the day and bright young things later at night. A sprinkling of connected Chinese sometimes joined the crowd, as did the children of wealthy local businessmen who’d just returned from Paris or London. The Wagons Lits had always been a place to loosen tongues. There were tables to be had away from the dance floor, away from the band that strummed lightly for the mix of guests. This was the spot to meet the knowledgeable and opinionated old China hands.