Milo and One Dead Angry Druid (3 page)

Read Milo and One Dead Angry Druid Online

Authors: Mary Arrigan

W

e looked at one another for a few moments, him and me. The funny thing was, he seemed just as scared of me as I was of him.

So I said, ‘Hello.’

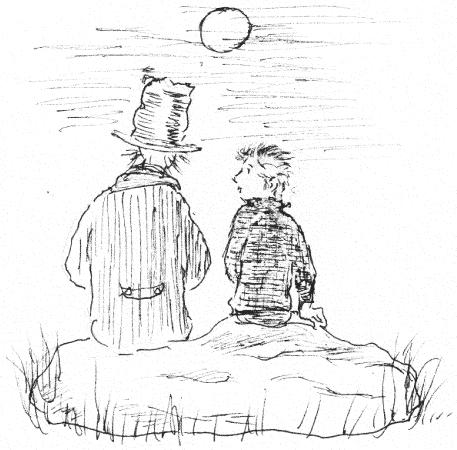

He nodded and came towards me. I noticed his clothes. I’m not much into

fashions − so long as I have the current Man United strip I don’t much care what other people wear. But I could see that this guy was dressed like someone from one of those really old movies that you find on TV on a wet Sunday. Long coat, tall hat like a chimney pot, and hair that grew right down in front of his ears. Anyone, dead or alive, who went about like that could only be a harmless twit. Maybe. Hopefully.

‘Who … who are you?’ I croaked. Not the most clever question, but cleverness doesn’t really kick in when you’re scared.

‘Lewis. Deceased, as in dead,’ the spook replied. ‘Mister Arthur Albert Lewis to you, boy. And who are you?’

‘Milo,’ I said. ‘Mister Milo Ferdinand Doyle to you.’ I never ever tell anyone about the Ferdinand bit, but it seemed

right just then. ‘And what are you doing here? Are you the Lewis man who used to live here? The one who collected stones?’

‘Ah, yes,’ said Mister Arthur Albert Lewis, sitting down on one of Big Ella’s dug-up stones. ‘Well, Milo Ferdinand Doyle. We’re in deep trouble here, sir. Deep, deep trouble.’

It was the ‘we’ part I didn’t much like. So I sat down − near enough to hear what he was saying, but far enough to run if he made a spooky move in my direction.

Mister Lewis let out a sigh and leaned forward. ‘It’s to do with a special stone,’ he went on.

Ah, I might have guessed. ‘One with roundy patterns and a lizardy thing carved on it?’ I asked.

He nodded very slowly and carefully, as one would, I suppose, if one was that

ancient. And dead.

Mister Lewis looked at me with staring eyes. ‘You know it?’ he said.

‘Sort of,’ I replied, not adding that it was in the bag I was carrying. ‘What about it?’

He gave another deep sigh. I wondered if spooks had lungs.

â

I

t's all to do with the ancient Celts,' Mister Lewis went on. âThat stone is a sacred stone that the Celts brought with them as they were chased across Europe by the Roman army. When the first Celts arrived here, they decided that Ireland would be the place to live.'

âThey hadn't much choice,' I put in. âThis would have been the last bus stop after Europe. Any further and they'd have drowned in the Atlantic Ocean.'

Mister Lewis scowled. âDon't interrupt, boy,' he said. âThis is serious.'

âSorry,' I said. âGo on.'

âWell, they made a ceremonial circle right here in the middle of Ireland, and their druid placed the stone in the centre. From then on, that stone was the most important thing to the Celts.'

âHow do you know all this?' I asked.

âBecause I'm a historian,' replied Mister Lewis grandly.

â

Was

,' I said.

âNo need to remind me,' muttered Mister Lewis. âAnyway, when I was digging here I discovered that stone â it was broken in

two. Then I dug deeper and I discovered the remains of the stone circle. I could scarcely believe it.'

âHow did you know what it was?'

Mister Lewis sniffed impatiently. âResearch, lad. That circle of stones went all around the nearby fields. When I realised its importance as a sacred place, I knew I'd have to cover it up and leave it in peace. So I bought any unusual stones from the farmers, at one penny each, to stop them being broken and scattered through ploughing or building. I thought if I simply buried them all together here I'd be doing a service to our ancestors. And yet â¦' he paused and put his head in his hands. Not in a ghostly way like those pictures you see of spooks carrying their heads around damp castles. No, this was a worried head-in-hands thing. Just like you

and me when there's a surprise maths test or a letter home from the school principal.

âAnd yet?' I prompted.

âAnd yet, as a historian, I felt I should pass part of my discovery on to heritage. So,' he paused again. âSo I buried one half of the circular stone. I gave the other half to the museum. I didn't say where I'd found it. I just made up a story about it.'

âIn case there would be lots of history types coming here poking around?' I asked.

âIndeed,' said Mister Lewis. âBut it wasn't the history types who were to bother me,' he said. âIt was Celts and their druid.

âHuh?' I exclaimed. âYou mean one of those ancient guys in long frocks? Sort of like witchdoctors who scared people with their weird chanting and mad spells? Wow! I used to think druids were just made up. So

druids were really real?'

Mister Lewis nodded. âI should have known they'd come for the stone.' He sniffed and wiped his dead nose on his sleeve. âJust like they've come for your friend and the big lady â¦'

I

tried to say something else, but my tonsils had freaked out. I'd have done a runner right there and then except that my knees were locked with fear.

âThat night, after I'd presented the

half-stone

to the museum,' Mister Lewis went on, âI was sitting in my study when a great

wind burst the door open, knocked my cocoa right out of my hand. Look,' he added, stretching out a skinny leg. âYou can still see the cocoa stains on my trousers. But then a figure emerged from the wind.'

âWho?' I whispered, looking about nervously.

Come on, knees, move!

But something about this sad spook made me want to know more. After all, my best mate was involved.

âAmergin,' replied Mister Lewis.

âAmergin? Should I know him?'

Mister Lewis shook his head. âHe was one of the first Irish druids,' he said. âIt was he who put the stone here originally. And he was very angry. Bloody angry, sir, if you'll pardon my forcefulness. Face like a bull in a rage.'

âBecause the stone was broken?'

âNo, it was because I had given away part of it. And that was the end of me,' he said with a sigh. âI was ⦠er ⦠taken away. Deceased â but don't worry,' he went on as I fell off the stone I'd been sitting on. âIt didn't hurt,' he said. âA quick demise â didn't really feel anything. No splutterings or gurgles or splashes of gore. Just a quiet draining of life from my head down through my toes.' He sighed and looked at his laced-up boots. âMy punishment was to guard this sacred place,' he went on. âNot too bad until that scary woman started digging.'

âYou've been here all those years?' I asked. âAll alone?'

âHere in this wilderness,' he replied. âI wouldn't mind if there was a bit of a garden to sit in, like when other people lived here. But since that big lady came with her

ecology-friendly madness, there's just all these weeds and dandelions. Look at them, lad. Talk about dreary! Why couldn't she just plant a few nice rosebushes and a flowery shrub or two, eh? Digging up the ancient stones, pah! Mad, interfering woman.'

Now was the time to sort all this. I had the solution. âTarra!' I said, lifting the tingly stone from the takeaway bag. I waited for Mister Lewis to dance â or have a happy float of joy with excitement, saying what a genius I was. He looked at the stone in my hand, but said nothing.

âIt's the stone,' I prompted. âThe one that Shane took. Now he can come back, eh? Him and Big Ella?'

Mister Lewis shook his head. âIt's not that easy,' he said. âWhen I said that Amergin was angry with me for separating the stone,

that's nothing to what he is now with your friend and his granny. Now he's

really

angry. He's insisting that the two parts are to be put together and buried together.'

âYeah? So why didn't you just spook your way into the museum and take the other half back?' I asked.

Mister Lewis snorted, then stuck back the bit of his nose that he'd snorted off. âHm,' he muttered, checking his nose carefully, âAmergin keeps doing this to me. Sick joke. And look,' he went on, leaning across and putting his two hands around the stone I was holding. As he tried to lift it, it just stayed put. âGhostly hands,' he said. âNo grip.'

âI see,' I said. âAnd ⦠and ⦠what about â¦' my throat dried up again and I nodded towards the dark house.

âYour friends?' said Mister Lewis. âWell,

that boy certainly stirred things up when he took the stone away. Until the two parts are united, the boy and his grandmother will end up like me, stuck in this draughty wilderness, minding a pile of stones for ever.'

âAre you saying that Shane and Big Ella are dead?' My heart kicked up. Would I never see my best mate again, except, perhaps, as a spook? Not able to share a bag of chips because he couldn't hold it, or kick a ball because his foot would go through it? Not much fun in that for Shane, even if it meant no homework.

âNot yet,' said Mister Lewis. âAmergin has them. They're in a trance â a sort of sleep. The only way to save them from ending up like me is to get the rest of the stone from the museum and bury the two parts together.' Mr Lewis paused and then leant

over and peered into my face. Whew, for a spook he had smelly breath and I really hoped all the bits of his face stayed put this time.

After a few moments of me staring up a spook's hairy nostril, he finally said, âI need you to help me break into the museum.'

Oh great, I thought, just great. Now I was really scared. Chatting with a spook is one thing, but getting involved in breaking and entering was another. But, hey, my best mate and his gran were in trouble. I couldn't abandon them. I took a deep breath.

âOK,' I muttered, even though I was screaming inside.

âThere will be a full moon tomorrow night,' said Mister Lewis, shaking his creaking head.

I wished he wouldn't do that. I so did not

want to see his head fall off.

âThat's the time to do it,' he continued. âThis has to take place on the night of a full moon.'

âWhy?'

âI don't know,' he said impatiently. âI'm only going on what Amergin told me. Some ceremony or something, I suppose. They were fussy about the sun and the moon in those days.'

âSo we only have tomorrow night to do this?' I said.

Mr Lewis's high hat wobbled as he nodded.

âWhat if we're late? What if we can't do this?'

âThen their bodies will be found next morning,' he sighed.

âNo way!' I exclaimed. âMister Lewis, I couldn't live with myself if this didn't work out.'

âWell, you wouldn't live with yourself at all, my friend,' said Mister Lewis. âNot now that you are part of all this.'

âWhat?' I croaked.

âYou'd be dead too, young sir.'