Mind and Emotions (22 page)

Authors: Matthew McKay

Watching is the best medicine for your emotions because it gives you some distance from what you’re feeling, along with a sense that you are not the feelings in your body. These sensations are nothing more than the changing color of the sea at twilight—now blue, now silver, now ebony. They are nothing more than a flash of lightning between storm clouds. They exist for just a moment in time and don’t define who you are at the core of your being.

When Renee began to observe the sensations that accompanied her sadness, she noticed a feeling of weight and torpor. Everything in her body seemed to slow down, and movement felt like a great effort. She also noticed a feeling of tension, like a hard rock, in her gut.

Over the next few weeks, she experienced waves of sadness that washed over her and lasted anywhere from several minutes to several hours. During these times, Renee focused on her body, describing to herself where the sensations occurred and how they felt. The heaviness and the rock in her stomach seemed fixed and unyielding, but Renee learned that as she kept watching, these feelings eventually changed, giving way to a sense of increased lightness or feelings of release around her diaphragm.

Applications

Use interoceptive emotion exposure for each problematic emotion you experience. The procedure is the same, regardless of whether you struggle with anxiety, depression, anger, or other emotions. Some emotions may trigger sensations that are more distressing. For some emotions you may have more items in your hierarchy, and for some sensations it may take more trials before your distress decreases to a 2. But none of this really matters. All you have to do is develop a separate hierarchy for each target emotion and continue exposure trials until you’ve reached a distress level of 2 or lower. If you keep doing trials until the sensations are only slightly uncomfortable, you’ll have taken a huge stride toward emotion regulation.

Duration

Depending on how frequently you practice, induced interoceptive emotion exposure should take somewhere from several days to several weeks—however long it takes to desensitize to the most distressing sensations caused by the twelve exercises. At that point, you’re finished. On the other hand, mindful exposure in daily life—watching for and habituating to the physical sensations that accompany difficult emotions—is an important part of taking care of yourself and maintaining good emotion regulation. Facing and observing these experiences, rather than trying to escape them, is a lifelong project.

Chapter 13

Situational Emotion Exposure

What Is It?

Situational emotion exposure is sometimes called in vivo exposure, since it involves experiencing, in real life, what you typically tend to avoid. It’s the logical extension of the imagery-based and interoceptive emotion approaches you learned in the two previous chapters.

Situational emotion exposure is the exact opposite of avoidance. Instead of avoiding scary, depressing, worrisome, or infuriating things, you actively seek them out. But you do it in a systematic, controlled way so your feelings don’t overwhelm you. Over time you become desensitized and habituated to problematic experiences. In other words, you gradually get used to things that you previously thought you couldn’t stand.

Situational emotion exposure is an important component of both acceptance and commitment therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy. Acceptance and commitment therapy researchers call it values-based exposure and have shown it to be effective in situations that relate to a person’s values (Eifert and Forsyth 2005). Cognitive behavioral researchers call it situational emotional exposure and have found it to be effective in reducing avoidant behaviors (Moses and Barlow 2006; Allen, McHugh, and Barlow 2008).

Why Do It?

Situational emotion exposure can help you minimize your emotional suffering and have a fuller, more active, and more satisfying life. Avoiding people, places, things, activities, or situations you find uncomfortable might shelter you from pain in the short term, but it inevitably leads to greater emotional vulnerability and a restricted life.

Lynn, a journalist in her thirties, provides a good example of how this works. Once when she was driving on the freeway, she had a panic attack that was so severe she had to pull over and ask her husband to pick her up. As a result, Lynn developed a fear of having another panic attack when driving on the freeway, so she started spending a lot of time trying to figure out how to get around by driving only on surface streets or using public transportation. This initially seemed like a good idea, but it caused Lynn significant problems in the long term. She started having problems at work because she was often late for appointments or turned down assignments because she thought they were too far away. Lynn’s family life also was affected because she started asking her husband to take side streets when he drove to family events or gatherings with friends. In a period of six months, Lynn received two warning letters from her employer, had several arguments with her husband, missed get-togethers with family and friends, and started experiencing depression in addition to anxiety.

The more you can approach, confront, and tolerate what you find frightening or depressing, the more freedom and, ultimately, enjoyment you’ll find in your life, just like Lynn did. She used the systematic steps of situational emotion exposure, which you’ll learn in this chapter, to gradually reduce her fear, starting by contemplating a trip on the freeway, then actually being on the freeway as a passenger, and ultimately driving on the freeway herself. In three months she was able to return to driving, as she put it, “like a normal person—sometimes nervous, but not panicked.”

Situational emotion exposure is a powerful technique that directly targets the transdiagnostic factor experiential avoidance. Instead of avoiding certain people, places, and things, you learn to cope with your painful feelings by remaining in problematic situations until the feelings run their full course. Indirectly, situational emotion exposure also addresses three other transdiagnostic factors: It short-circuits rumination, turns short-term focus into long-term success, and breaks up the inflexibility of response persistence.

What to Do

Situational emotion exposure is a three-step process. First you need to identify the situations you tend to avoid and choose which general area you’d like to work on. Eventually, you may want to use exposure for several different types of situations, but at the outset, you’ll choose one type of real-life situation that you tend to avoid. The second step is creating an exposure hierarchy, similar to the hierarchy of physical sensations in the previous chapter, but this time using real-life experiences. The third and final step is to practice real-life situational emotion exposure, working through the hierarchy you’ve created, starting with the least distressing situation and working your way up.

Choosing an Area to Work On

The first step in situational emotion exposure is to identify an area to work on—an aspect of life where you avoid a variety of situations. In choosing an area and, ultimately, which situations to list, let your values be your guide. What do you really want to do or get out of life? What have your painful feelings kept you from doing? If you aren’t sure what’s most important to you, you may find it helpful to review chapter 4, Values in Action.

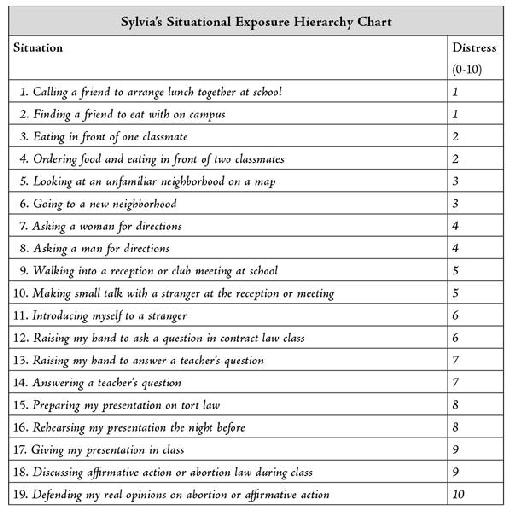

Here’s an example to give you an idea of which areas and types of situations to target. Sylvia, a thirty-five-year-old law student, had both social phobia and a fear of big dogs. She decided to work on her social phobia first, since it was keeping her from participating and doing well in her classes. Being comfortable around teachers and other students was more important to her than being able to tolerate big dogs. If Sylvia had been engaged to a dog trainer or interested in volunteering for a search and rescue team, she might have chosen to work on her dog phobia first.

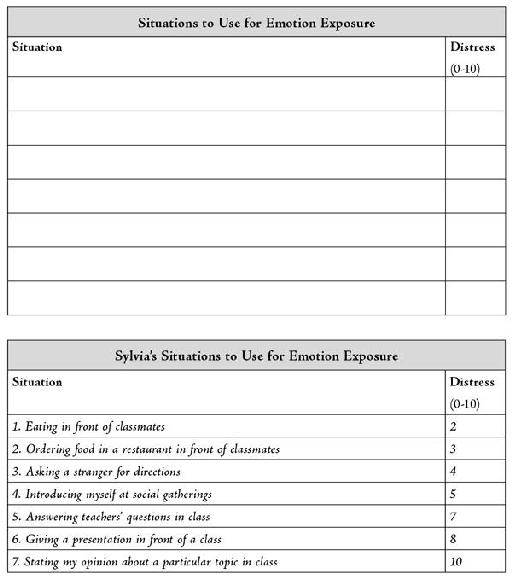

Creating a Situational Emotion Exposure Hierarchy

Once you’ve identified the general area you want to work on, come up with a list of specific situations you’ve been avoiding, and enter the items on the following page. Choose situations that you can initiate and repeat yourself. For example, Sylvia felt anxious talking to strangers on the street. At one point she described an avoidance situation in which a stranger asked her for directions, but then she realized that she had no control over what strangers would do or when, so she changed that item to “Asking a stranger for directions,” which she could initiate herself and repeat as often as she liked. If you need some help getting started, an example from Sylvia follows the blank form.

AVOIDANCE SITUATIONS

_______________

_______________

_______________

_______________

_______________

_______________

_______________

_______________

_______________

SYLVIA’S AVOIDANCE SITUATIONS

Answering teachers’ questions in class

Introducing myself at social gatherings

Giving a presentation in front of a class

Asking a stranger for directions

Stating my opinion about a particular topic in class

Ordering food in a restaurant in front of classmates

Eating in front of classmates

Now go back over your list and rank each situation according to how difficult it is, using a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is no distress and 10 is the highest level of distress.

When you’ve ranked each situation, rewrite your list in ascending order of stressfulness, starting with the least stressful situation at the top and working down to the most stressful at the bottom. Make copies of the blank form so you can use it for other types of situations in the future. Again, an example from Sylvia follows the blank form.

This rearranged list is the hierarchy you’ll use for situational emotion exposure, starting with the situation that causes you the least distress and moving progressively through situations of increasing difficulty. For this progression to be smooth and continuous, you should expand your list until you have between eight and twenty situations. The idea is for each situation to be just a bit more challenging than the one before. Here are four variables you can use to expand and refine your hierarchy:

- Spatial proximity.

Arrange your hierarchy so that you get closer and closer to the feared situation. For example, if high places make you nervous, you could introduce the following variations: entering the lobby of a skyscraper; taking an elevator up to the fifth floor and going back down; taking an elevator up to the thirtieth floor and immediately going back down; and, finally, taking an elevator up to the thirtieth floor, approaching a window, and looking out. - Temporal proximity or duration.

Another way to expand your hierarchy is to make a particular situation closer and closer in time. For example, if you’re depressed and have been evading your parents’ attempts to come for a visit, you could first talk to them and set a date for them to visit, then make a second call in which you arrange the details of their visit. Then, on the day of their arrival you could see them briefly at their hotel, and, finally, you could have them over to your house for lunch the next day. - Degree of threat.

You can also vary the degree of threat associated with a particular type of situation. For example, if you tend to avoid crowds, you can construct several situations in which the size of the crowd gradually gets larger. - Degree of support.

Initially, you can ask a supportive person to be present to make difficult steps in your hierarchy less threatening. For example, if you don’t like going to the doctor, you might make that situation less threatening by having your spouse or a friend take you and stay in the examining room with you. Next, you could have your support person stay in the waiting room while you’re being examined. Finally, you could go to a doctor’s appointment alone.

Sylvia used all of these variables to expand her hierarchy to nineteen situations. For example, she expanded “Asking a stranger for directions” into “Asking a woman for directions” and “Asking a man for directions,” since she found it easier to approach women than men. Following you can see how Sylvia’s complete exposure hierarchy turned out. Notice how the levels of distress increase very gradually and evenly.