Mission: Cook! (15 page)

To serve, run a sharp knife around edge of the pan to loosen the pastry. Cover with a serving plate and, holding them tightly, carefully invert the pan and plate together. (Do this carefully, preferably over the sink, in case any caramel drips.) Lift off the pan and loosen any apples that stick with a spatula. Serve the tart warm with cream.

A Note on the Tarte Tatin Pan

The tarte tatin pan is actually designed and named for the “upside-down” dessert that originated in France. It is a stovetop-to-oven vessel with handles on the sides, which facilitate the smooth rotation of the tart onto the serving plate. Some of these pans are made of porcelain over cast iron, some are entirely made of metal or of heatproof glass or glasslike material. You can actually use any stovetop-to-oven pan that is 10 inches in diameter and 2 inches deep, which will be easy enough to handle when flipping.

I

F YOU STOP AND TAKE A GOOD LOOK AT THE GOURMET ITEMS ON YOUR

plate next time you're eating in a fancy restaurant, you might easily ask yourself, “Who ever figured out that this was something good to eat?” Oysters immediately come to mind. How about the early Japanese fisherman (and probable sushi chef ancestor) who captured a sea urchin or an octopus in his net and decided he just had to find out how they tasted? Who was the guy who decided that fermented, moldy milk had the potential to become cheese and not garbage? Was it a French gardener who ate the first escargot? I mean, come on, how hungry do you have to be?

What adventuresome diner first had the patience to eat his way through an entire artichoke, leaf by leaf? I have heard eating an artichoke compared to licking thirty or forty postage stamps. Yet we know that when it's mated with a nice lemon yogurt dressing or a little crème fraïche, or when the hearts are marinated with a fine olive oil and fresh herbs, an artichoke is a wonder to behold.

So, experimentation obviously came into play in early culinary exploration. You watch a bird or an animal eat a plant (or each other), and maybe you give it a try. If your fellow tribesman tries some and dies, you give it a pass next time around. Pretty soon, you've got it narrowed down to what's good to eat and what's not.

But it doesn't stop there. Ingredients are combined, and recipes are born, because human beings are driven by something else. Why not just stick with berries and apples and the occasional haunch of wild goat?

The answer is

pleasure.

That good old culinary quote machine, Brillat-Savarin, said, “The discovery of a new dish does more for human happiness than the discovery of a new star,” and I heartily agree. There are over nine thousand taste buds on the human tongue, and every one of them is looking for a good time.

The discovery of pleasure through food can be a satisfying and lifelong pursuit, because the variety of dishes and ingredients are as infinite as words in the English language. Each dish is like a new sentence, each meal is a paragraph, and we all progress through chapters of eating in our lives, from the simple, beloved, and memorable meals we eat as a child to the widerranging explorations that transport us out of the safe strictures of the commonplace. We choose different themes as we go; some of us eat for health, some of us overindulge, happily or unhappily, comically or tragically; some, like Craig Claiborne or M.F.K. Fisher, find a level of refinement in their choices

to rival the greatest prose; some seek adventure, some comfort, others, romance; some celebrate family and friends with every meal, some choose to dine alone. Some write poetry, some short stories, some novels, but in many ways, the way we eat and think about food forms a large part of the narrative of our lives.

THE ALTAR OF FLAVOR

Making breakfast for Her Majesty, the Queen, and musings on the essential meaning of good taste

I

N MY TIME WITH THE ROYALS, I SPENT QUITE A LOT OF MY FREE HOURS

exploring new techniques, seeking out instruction with master chefs, and having new culinary and dining experiences to broaden the range of my skills and palate. But my time in direct service to Her Majesty, the Queen, and her family gave me a different level of appreciation for the importance of the notion that, in many ways, the truest test of skill for a chef is to coax out and put on display the maximum amount of flavor from the

simplest

ingredients and preparations.

The most surprising thing you have to know about the Royal Family is that for all of their vast estates and holdings, all of their fame and responsibilities, all of their charms, intrigues, and eccentricities, at their core I believe they are a typical English family. Because of the intense scrutiny they receive from subjects and press, the constant examination under which they live their lives, even in their own homes, where they are perpetually, if respectfully, under the watchful gaze of servants, staff, and courtiers, they are essentially a typical English family in a very

concentrated

form. If the eligible son of a respectable English mother decides to marry the pretty daughter of friends of the family in the local chapel, you can be sure that a splendid time will be had by all the locals at the ceremony. If the same happens in the Royal English family, Western civilization as we know it stops and watches until the vows have been spoken.

It wouldn't take a huge leap of imagination in your mind's eye to see Her Majesty, sans crown and scepter, padding into a warm kitchen in a typical English cottage home, in housecoat and slippers, and greeting her affable husband, who patiently waits for his breakfast to arrive whilst he examines the football scores in his paper. She affectionately pats her aged mother, at the other side of the table, who is stationed behind her empty cup in anticipation of her usual breakfast tea. The Queen puts the kettle on. A gentle tap on the back door precedes the entrance of her eldest son, who has stopped by on his way to work because he has a few papers for Mum to sign, just boring family business. He is a likable chap, slightly awkward, but a well-respected citizen in their little community. She worries about him. She knows he works hard and is responsible,

but she also knows that in his heart he has always longed for the simple country life. She hopes he can find happiness in marriage someday. She fishes the bacon out of the icebox and puts the pan on the stove. She asks her son to stay for a bite, but duty calls; he's late to the office and must be off.

Then, out of nowhere, imagine that

I

appear to take over cooking breakfast for everybody whilst she is suddenly freed to relax and watch the BBC morning news on the telly!

That is a pretty good analogy for the routine of cooking for the Royal Family. They don't spend their idle time scanning newly published cookbooks looking for exciting recipes that they can send down to the galleys to spice up Wednesday dinner. They like what they like and they generally like it to be simple and consistent.

A regular breakfast for Her Majesty, whether at one of the palaces or on the Royal Yacht, would be fried eggs and bacon served with tea and chilled freshly squeezed orange juice. There are at all times, of course, an array of breakfast items that can be ordered, such as poached eggs and chipolatas (small English breakfast sausages), fish cakes, kippers, sautéed kidneys, smoked haddock; the list goes on and on. If you are ever fortunate enough to be invited to breakfast at Buckingham Palace, please feel free to order up as much as you'd like, but Her Majesty will most likely be contented with fried eggs and bacon, her tea, and chilled freshly squeezed orange juice.

At one of the palaces, there would probably be a snack around elevensy, which would consist of hot tea and good tinned biscuits (

cookies,

in the colonies). Each day, the Queen selects the afternoon and evening meals from menu books, leatherbound in either red or black, inscribed on the cover with the words “Menu Royal.” They are beautifully bound volumes, and you wouldn't be surprised if a trumpet sounded when you opened the cover. Inside are written suggestions from the chef for the day's menu, invariably fashioned to please the royal palate. She marks her selections in pencil, making additional notes if she wants something that isn't on that particular day's carte du jour, then the book is returned back to the kitchens and we go to work. These books also contain any special or unusual dishes that might have been prepared for visiting dignitaries or heads of state if they have dined privately with the Queen. The esteemed visitor's name is duly placed thereby. Once filled, these volumes are stored and cataloged in the Royal Library as part of the official record of the reign of Elizabeth II. These books stretch back into the history of the monarchy. There are a lot of fried eggs in these books.

Depending on the day of the week and travel schedules, lunches usually consisted of four dishes, and were generally catered for up to eight people, depending

on which family members were about and what invited guests were expected. A typical lunch would feature smoked salmon, a roast veal or beef with two vegetables, a dessert, and cheeses. There are few if any English homes that haven't put on a lunch of “meat and two veg,” sweets for after, and “a bit of cheese would be lovely.” No tacos, no dim sum, no spaghetti alla puttanesca, no egg rolls, no cheese steaks, no turkey wraps, no big Greek salad with extra dressing on the side, no pizza, no gyros, and no knishes. I think I can say with little fear of contradiction that if you went down to the diner with Her Majesty, the Queen of England, she might try the fried chicken, but she will not be ordering the chili.

The menus for the Royal Family, on every occasion, were written in French, which was very elegant, but a thinly veiled disguise for some simple, homey dishes.

MENU ROYAL

Cottage Pie

de Boeuf braisé

(In reality, cottage pie with ground beef, veggies, and mash)

Navarin d'Agneau aux Legumes

(A savory lamb stew)

Côtelettes d'Agneau

(Tasty grilled lamb chops)

Rumpsteak

Grillé Béarnaise

(A nice grilled steak with a béarnaise sauce)

You could have all of these dishes down the pub, although I have to admit we used to do a very nice job on them. You'll also note that there is a bit of a nod to understandability for the English eye on these menus. Cottage pie could be translated

as pâte en croâte de petite maison,

but that might be pretentious and nobody would order it.

On the

Britannia

and at Windsor or Buckingham palaces, we always tried to show off the best of English food: salmon, hare, grouse, turkey roasts, partridge, venison, potatoes, sprouts, chutneys, pear tarts, and the like. This is where I learned a fundamental truth about cooking that every chef and cook should know. If you shop well, you can cook well. That simply means that the better your ingredients, the better your flavors. It is very nice when your

venison and beef is culled from the royal herds at Balmoral Estate, when your honey for biscuits comes from one of the 450 hives on the estate, when your salmon is freshly caught from the River Dee in Scotland, which borders your employers' property. Often is the time when the Royal Game Warden would deliver freshly shot grouse, pheasant, or quail to our kitchens, which we would butcher, hang, and dress for that evening's dinner.

The flavors available to you from these kinds of ingredients are pristine. You have to care for them, cherish them and, for the most part, stay out of their way. This need is accentuated when the taste buds of your employers are finely attuned to the simple perfection of these flavors, since they have been served them virtually from birth.

Traveling with the Royal Family is much the same routine. On a number of different levels, the rule when you are traveling in a personal retinue is: take care of your principal. I often traveled with the Prince and Princess of Wales, Charles and Diana. I had to be trained not only in protocol and etiquette but also in evasive driving and small arms. The president of the United States travels with literally hundreds of people when he moves and is accompanied by a huge security force. The Royals usually moved with small parties, often just me, a small advance team, and a couple of butlers. In crowds, the principal is the star and your job is to be as invisible and as available to them as possible. On the food side, my job was to make sure that the menus wherever we stayed were what they wanted and were appropriate to the occasion. That often meant consulting with the chefs on site and supervising their preparations. We spanned the globe, from Australia and New Zealand to America to the Far East, from Boston to Brindisi to Bahrain, and were as likely to be cooking for the sultan of Oman as Elton John. Outside of England or the Royal Yacht, I seldom did a lot of “hands-on” cooking.

A big part of our accepted practice for high-profile public affairs at home was to dig into the family archives, the Menus Royal, not unlike the way you might dig out a worn scrap with Grandma's potato salad or that Swedish meatballs recipe Great Granddad liked so much on it. These affairs might take four days to prep and cook, and might feature a VIP gathering of two hundred dining personally with Charles and Diana, and an additional thousand dining otherwise. We might pull a recipe for

Mayonnaise de Homard,

or lobster salad, from the coronation banquet of His Majesty, George VI, from May 1937, and a

Filet de Boeuf Mascotte,

a whole roasted tenderloin of beef with artichoke, whole peeled truffles, and parsley, from the coronation day feast of Her Majesty, Elizabeth II, from June 1953. She'll like that. A

Salade d'Asperges à la Vinaigrette,

or roast asparagus with dressing, from the tables of Albert and

Victoria might go nicely, and didn't we whip up a

Parfait à la Meringue au Citron,

a frozen lemon and orange soufflé, when the president of Finland came over that time?

I was generally consulted for state affairs and remember particularly helping to make some of the menu decisions for a birthday dinner for President Reagan, which was celebrated on the yacht in the port of San Diego, but for the most part, the Queen herself always made the final decisions about the bill of fare. The Master of the Household, who is essentially the head of all “below stairs” operations for the family, provided me with the itinerary, and menus were often determined four or five weeks in advance. I worked the galleys with another cook named Jan Yoeman, the big guy, and given my basic nature, I would persistently look at him and say, “Why don't we try it this way? Why are we doing it like that?” to which his reply was always, “Because she likes it that way.” In our business, the customer is always right.

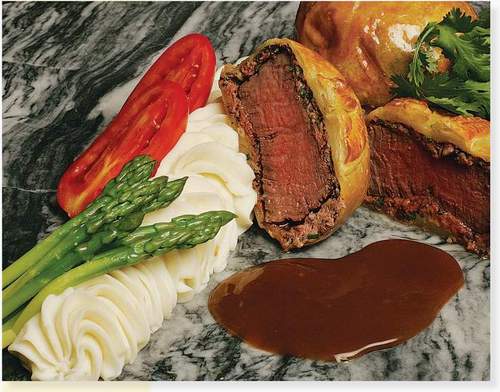

There's something very “regal,” yet homey about Beef Wellington, so in honor of Her Royal Majesty, may I presentâ¦

SERVES 6 TO 8

FOR THE BEEF

1 whole filet (beef tenderloin, about 5 pounds) or six 5-ounce filets (see Note at left)

6 ounces (1

3

/

4

sticks or 10 tablespoons) unsalted butter, melted

Salt and pepper

4 ounces (1 stick) unsalted butter

1 onion, minced

2 ounces sliced mushrooms

1 teaspoon chopped fresh thyme

½ pound goose liver pâté or duck liver pâté

2 tablespoons red wine

1 large package of frozen puff pastry (1 to 1½ pounds)

2 egg yolks

This dish can be done using either a whole beef tenderloin or individual 5- or 6-ounce filets. The choice is yours.

Preheat

THE OVEN TO 425 DEGREES.

In a large roasting pan, arrange the whole filet, brush with melted butter, and season with salt and pepper to taste.

Roast in the oven for about 30 minutes until a meat thermometer reads an internal temperature of 115 degrees.

Note:

If you are using individual filets, season the filets, and in a large sauté pan, sear on both sides until golden brown and remove from the pan to cool. Then follow the rest of the steps.

Remove from the oven and let the filet rest for 30 to 40 minutes, or until the meat is cold. The meat has to be coldâotherwise, the pastry will become soft and unworkable.

Leave the oven on, as you will need it again shortly.

Using a large skillet or sauté pan, add the 1 stick butter and cook the onion until translucent. Add the mushrooms, thyme, pâté, and red wine, and cook until all the liquid has evaporated and the mixture is almost dry. (The mixture will resemble a coarse pâté.) When you reach this point, you can adjust the seasoning with salt and pepper, and set aside to cool.