Mission: Cook! (24 page)

Cut

the eggplant into ½-inch-thick slices. Quarter the red and yellow peppers and remove the seeds and stems. Slice the zucchini and squash lengthwise into ¼-inch-thick slices. Cut the onion into ½-inch-thick disks. The portobello mushrooms will be left whole, but clean the black gills off the portobellos. Brush all the vegetables lightly with oil, salt, and pepper.

Place the eggplant, red pepper, yellow pepper, zucchini, yellow squash, onion, and mushrooms on a grill and cook over medium-high heat, turning occasionally until tender and slightly charred, 10 to 12 minutes. Remove the vegetables from the grill. Cut the portobellos into 1-inch strips. Cut the peppers into

3

/

4

-inch strips.

To make the pesto dressing, place the basil in a food processor, add the pine nuts and garlic, and blend. Add the Parmesan cheese. With the food processor running, add the oil slowly through the feed tube. Stop and scrape down the sides, and add black pepper to taste. Blend the pesto until it forms a thick, smooth paste.

Basil pesto will keep in the refrigerator for one week.

To assemble the dish, place all the grilled vegetables in a mixing bowl. Add enough pesto dressing to coat.

PRESENTATION

Serve in a large bowl and drizzle with 8-year balsamic vinegar. Garnish with basil sprigs and shaved Parmesan cheese.

SERVES

4

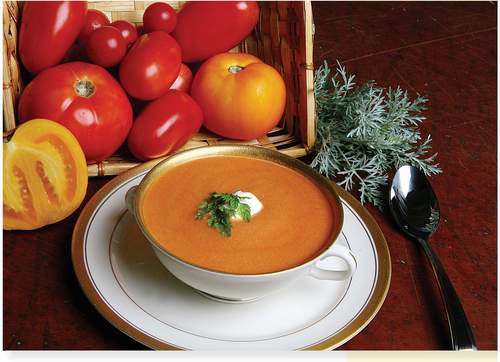

1 tablespoon olive oil

1 large onion, chopped

1 carrot, chopped

2¼ pounds ripe tomatoes, cored and quartered

2 garlic cloves, chopped

5 sprigs of thyme, or ¼ teaspoon dried thyme

4 to 5 marjoram sprigs (reserve 1 for garnish), or ¼ teaspoon dried marjoram

1 bay leaf

3 tablespoons crème fraïche (or sour cream or yogurt) plus a little extra to garnish

Salt and freshly ground black pepper

Heat

the olive oil in a large, preferably stainless-steel saucepan or flameproof casserole.

Add the onion and carrot, and cook over medium heat for 3 to 4 minutes until just softened, stirring occasionally.

Add the tomatoes, garlic, thyme, marjoram, and bay leaf. (Remember to reserve a marjoram sprig for garnish.) Reduce the heat and simmer the

soup, covered, for 30 minutes. Remove the bay leaf. Add 2 cups water if necessary.

Pass the soup through a food mill or press through a sieve into the pan. Stir in the crème fraïche (or sour cream or yogurt) and season with salt and pepper as needed. Reheat gently and serve garnished with a spoonful of crème fraïche and a sprig of marjoram.

I

N MY OPINION, THE MOST IMPORTANT THING IN MAINTAINING NUTRI

- tional health is to strive for balance. I am not a diet guru and I am not a health advocate, I am a chef. I believe in food. I believe that the body responds to the skills of the chef, in his or her discrimination and judgment of ingredients, menus, methods, combinations, and timing. Know your food, prepare it with care, and listen to your body, and your body will tell you, visually, physically, emotionally, and spiritually, when you are feeding it well. When it tells you, you will know it. You will be satisfied.

THE FRENCH GODFATHERS

One man's guide to surviving an education at the

merciless hands of French master chefs

Robert, George Kralle, and George Galati

I

T IS TREMENDOUSLY IMPORTANT TO KNOW AS MUCH AS YOU CAN ABOUT

the foundations of your profession and, if at all possible, to learn from the best. I received the beginnings of a good culinary training in the Navy, and I expanded my horizons whenever I could through experimentation, reading, and talking to other cooks and to the people who ate my food. At twenty-two, I realized that I needed a grounding in classic French cuisine if I were truly to forge a career for myself in my chosen trade, so one day I took my leave from the tables of the Royal Family and somewhat naively showed up at the door of the Waterside Inn in the village of Bray, on the River Thames.

Anyone who is familiar with the culinary scene in England and the genesis of fine dining in the modern era in the British Isles will immediately recognize the name of the Waterside Inn. The proprietor of the establishment is a man named Michel Roux who, with his brother Albert, introduced the very soul of perfected

French cooking to Great Britain when they emigrated in the sixties. After a period of time spent cooking exclusively for the Cazelet and Rothschild families, they opened Le Gavroche in 1967. With that groundbreaking institution and later with the Waterside Inn, they were the only three-star Michelin chefs in England for decades. Marco Pierre White, Marcus Wareing, and Gordon Ramsay have all been through their kitchens, and so have I.

If you took Don Corleone, made him French, and multiplied by two, you would end up with Michel and Albert Roux. They were the undisputed godfathers of haute cuisine in England.

I made my way to the Waterside Inn, knocked on the door, and talked to the chef who was running the kitchen that day. I explained that I would like to see if I could work in with them sometime soon, because I wanted to learn from the best. I think he might have heard that line a time or two before, but he asked me to call him back later in the week and suggested that I come in that night for dinner.

I returned that night with a date. It seemed like a good idea to take a look around and at the same time impress a girl with good food, fine wine, and beautiful decor. The table settings, the ambience, the dress and demeanor of the waitstaff, right down to the busboys, was so pristine and elegant it was almost intimidating. I don't remember the girl's name, but I do remember the food. I had aubergine and chicken-liver galettes in a buttery tomato sauce, Dover sole with a red pepper coulis ringed with finely diced yellow peppers, a mille-feuille of melon, and raspberry Pavlova. I am not sure what I was expecting. I was about to spend nearly five hundred pounds, an amount equal to many multiples of my regular weekly pay packet, so my expectations were pretty high. If the fish came out looking like Carmen Miranda's hat ringed with exploding firecrackers, that wouldn't have surprised me at all. Instead of lots of flash and showiness, the truth of their food dawned on me slowly. It started when I noticed the way the yellow peppers that ringed the sole were cut. They were shaped like little diamonds, a lozenge cut, and they were each absolutely, exactly the same size. The flavors worked on you vaguely at first, then crept through your entire system. When I was a kid, a sauce was something like ketchup; you plopped it on something else without thinking about it, usually to improve something that was bland or overcooked to begin with. Here, the sauces worked as a counterpoint to perfection. The sole was fresh, lovingly presented as the essence of what sole should taste like; the coulis did not distract from the experience, it sweetened it, aided by the texture and freshness of the peppers. They had me.

I persisted, and checked in at the restaurant every free moment I had away from the Royal Family. I was allowed into the kitchen a week later. In fact, it is surprisingly easy to present yourself for apprenticeship to French master chefs for training. Once you have wrangled an invitation into the kitchen, you simply have to be prepared to work endlessly at the most menial tasks imaginable whilst being heaped with the most creative and lovingly confected abuse, if you are noticed at all, for an indeterminate period of time of their choosing, not yours, that inevitably stretches into years. Chefs need extra hands, they need workers, they need disciples, and on some level they need worshipers, and they will take you on. They will make it clear to you that you are not worth a bag of dirt from their home country. The dirt from their homeland can produce truffles. As far as they know, you are only good for scrubbing and carrying, until you prove otherwise. They will not pay youâ¦in money. But if you show them persistence and talent, they will reveal their treasures to you, and they will teach you, and they will make damn sure that their teaching sticks.

I spent the first eight weeks cleaning vegetables. Early on, “

Pah!

” was the phrase they most often applied to my fevered efforts. I was so unceasingly compared unfavorably to execrable matter, I was tempted to change the name on my passport to Robert

“Merde!”

Irvine. They had a favorite word in the Queen's English. Many of the letters in this word are contained in “firetruck” and “fruitcake,” and I believe it may be

rendered fûcque

in the medieval Gallic. Their accents were thick and French, like a good hearty bisque, and they would often shout for my amusement, “What

the firetruck

do you think you are doing?!”; or “Who

the fruitcake

told you to do it that way, you piece of execrable matter?!”; “You are absolutely

the fruitcaking

worst I have ever seen!”;

“Firetruck

you!”

Under the tutelage of Albert and Michel, I learned nearly everything that matters in the life of a professional culinarian. The Brothers Roux were tyrannical, methodical taskmasters, and their food was brilliant. Albert could most often be found at Le Gavroche; for most of my tenure, I was with Michel at the Waterside. It didn't matter where they were physically; philosophically they were of one mind. Michel was very specific with me about knife skills. You would try something new, show it to him, and he would send it back. He sent everything back. When you tournéd a carrot, you wanted to end up with a barrel cut, with pieces approximately fifty millimeters long, with seven equal facets. The word “approximately” was not in his vocabulary, and you would end up doing it a

million

times.

In the first year, I progressed from vegetables to fish to sauces. They taught

you to keep everything and use everything, from bones, skins, and peels and ends of vegetables for stocks; to meat and seafood trimmings, which were built into terrines and galantines; to eggshells, which were used to clarify stocks. I often brought Michel coffee or tea and made his lunch. Every dish you made for him was a test. He would demand

“Coquilles St. Jacques,”

and if the plate you brought back fell short of his standards, into the garbage it went. And make no mistake, the standards were theirs, not yours. You were not permitted to vary an iota from their recipes.

The Rouxs focused on bringing out two qualities to a finely honed edge in their pupils: consistency and discipline; Everything else could be left to your native culinary talent, but if these two qualities were absorbed, they could be satisfied that you would always be of some use in a kitchen. In my second and third years, I learned the preparation of stocks, the methods of building them over hours of patient attribution, and proper techniques for the cutting of vegetables with machinelike precision; I learned mother sauces, béchamels and veloutés and their offspring, béarnaises and Mornays, the entire complicated and ethereal catalog; I learned emulsions and forcemeats and the arts of the

pâtissier,

the

rôtisseur,

and the garde-manger. I learned to create both

pâté à choux

and

pâté en croûte

by reflex, to sauté by nerve memory, to butcher and fillet on automatic pilot, to create a menu in my sleep.

There was precious little sleep in the four years I spent running out to Bray on practically every available minute of leave time I had from dishing up dinners to the Royals. In my fourth year, I had a personal breakthrough when I was working sauces for the Rouxs. I had produced a

sauce marzan,

a hollandaise variation with olives and cucumbers, silky and slightly salty, which was to accompany sole. I assembled it and tasted it. It was as if I felt a click in my head and I breathed in deeply. There are so many things that can go wrong with a sauce that when

everything

goes right, it can take your breath away. This was probably the best sauce I had made to that point in my life. But you couldn't just run up to Michel with a spoon in your hand and say, “Dude,

you gotta

try this!” When you had finished the sauces for the day, you would line them up and place a small silver tasting spoon in front of each one, each spoon pointing straight to the sauce with military precision. He would dip in each spoon, taste, and if he said nothing to you, you knew that it was ready for service. I lined up

the

sauce last in the rank, and I took a chance. I left an extra tasting spoon just slightly off to the side, just slightly at an off angle, to suggest that it had been left there oh-so-inadvertently. Michel tasted each sauce in turn. When he came to

the

sauce, he tasted and I swear I saw a flicker in his eye. Maybe he breathed in just a little

more deeply. He rested the first spoon on the white linen placed there for the purpose. And then he reached for the second spoon. He tasted again. He told me I had done a good job, patted me on the back, and walked away. Patted me on the back. Pure, unadulterated triumph.

The day finally dawned when the brothers declared me eligible for my final Master Chef's testing. Clearing this hurdle can be a momentous achievement in a chef's career, especially in a European kitchen. A Master Chef's rating can mean the difference between a one-star placement and a three-star placement. My first reaction was “I'm not ready.” The peremptory response was “Yes, you are.” It wasn't put as a request; nothing in their kitchen ever was. This was to be a command performance.

In the time I had spent with them, I had cleared certain benchmarks along the way at their gentle mercies. I had passed my charcuterie, was judged able to make an acceptable terrine, a passable dodine, galantine, and mousseline (when I say passable, that means it passes muster with two three-star Michelin chefs; that means that they found pleasure in seeing and eating it), and make cold aspics and jellies. I had mastered the lozenge, rondelle, and tourné cuts for decorative vegetables. I could roast, I could braise. I managed my time properly and did not create excessive waste when I worked. I understood not only the substance of the foods I worked with, their critically measured and calibrated relationships to one another, but I understood context, the visual appeal of food, the use of aromas, of proper delivery to table, neither too hot nor too cold nor too long a wait. I also knew what foods were needed when in the kitchen. I was organized; I had skills.

The final push lasted about four days, and the Roux brothers judged my performance along with a third Master Chef, who graded dish after dish, forkful after forkful, bite after bite. I would receive an order, go off to the kitchen, and work as hard as I possibly could, to come as close to perfection as I could possibly manage. The days were sixteen to eighteen hours long and I was a nervous wreck. There was no running update, no conversation, no encouragement. You put the dish down and walked away. Some of the dishes I created along strictly classic lines; in others, I allowed for inspiration based on what was at hand, or on forms and flavors suggested to me by the food itself, its freshness, its texture, the time of year, informed by the preferences and prejudices of the men for whom I was preparing the food.

They had watched me come along for four years. In the end, after dissection, criticism, consultation, comparison and, most of all, after tasting, they awarded me my Master Chef certificate and medal. Apparently, I could cook.

Years after I achieved my master's certification with the Rouxs and left the Navy, I joined Celebrity Cruises as executive chef. In those days, I was out to make a mark for myself. In some cases, we were turning out 25,000 meals a day, and I was in charge of purchasing, organization, quality control, and menus. I was learning quickly about life in kitchens that weren't necessarily filled with young British guys. I worked with enough Ecuadoreans to learn how to say incredibly nasty things to people in a tongue other than my native English. We cruised all over, from Philadelphia to the Panama Canal, and in each port, I was taking the opportunity to source local ingredients for use on our ships. My food was consistently judged by our passenger satisfaction rating with a score of 9.9 out of a possible 10.

Albert and Michel were hired as consultants to the line, and their familiar menu items started to appear from headquarters. The menus and recipes were very good, of course, but in my new station in life, I felt confident enough to change them as I saw fit. I changed their marinades and cuts; I served variations on their recipes, their trout in pastry with saffron sauce, tournedos of beef with goose liver pâté en croûte. I introduced specials on the menu each day of my own creation, and I even put liver and onions on at lunch because it was a favorite of mine.