Moloka'i (52 page)

The clerk nodded. “Marriage licenses and certificates from 1910 on. Before that they were kept in a ledger, but we type it up and send it to you.”

“Could I get a copy of my sister’s license? So I can find out what her last name is now?”

The woman looked at her sadly. “Daughter, sister . . . you lose a lotta people, huh?”

“Yes. A lot.”

“You know where she got married?”

“No, I’m sorry.”

“Okay, no problem.” The woman reached under the desk, took out a form, slid it toward her. “Fill this out, give your name, address, one dollar fee, we mail you a copy of the certificate.” She gave her a pen and watched as Rachel methodically filled out the form in block letters with her left hand. The clerk’s gaze slid down to Rachel’s other hand and her eyebrows arched a little. When Rachel had finished the woman scanned the form. “Rachel Kalama Utagawa,” she said; and then, “You out on T.R., Mrs. Utagawa?”

Rachel nodded, steeling herself. “Yes.”

But the woman just smiled. “Good for you,” she said. “You got the address for Vineyard Street Clinic, where you go for check-ups?” She scribbled down an address and handed it to Rachel. “We’ll mail you your sister’s marriage license, if we got it.”

“Thank you.”

“Good luck, Mrs. Utagawa.”

Rachel then made her way to the U.S. District Courts Building, where she was asked to put in writing her request for Ruth’s adoption papers to be unsealed. The formality of it all, the sober granite face of the building, gave her pause. Did she really want to do this? What if Ruth didn’t want to meet her birth mother? A thousand questions presented themselves, a thousand reasons not to do it. But there had also been hundreds, maybe thousands of patients at Kalaupapa who had died without ever having the opportunity to see their children again. Rachel had a chance now at something they would have killed for; could she just throw that away?

She handed her written request to the court clerk, was told that a court date would be set to hear her petition, and hurried out before she could change her mind.

I

nevitably, Rachel found herself staring up at a two-story stucco apartment building two blocks from Queen Emma Street, which now stood on the lot where her childhood home had once been. There was not a trace left of the house in which she’d spent her happiest years; Filipino and Japanese children played just as happily upon its grounds, but not a reminder anywhere of little Rachel Kalama, her family, or the life she had led. And she grieved to realize that the home she had so loved existed now only in memory, as distant and insubstantial as the kingdom in which she’d been born.

It was thirty years since Papa had told her about Kimo selling shoes at McInerny’s, but she hoped someone there might know where he was today. At the corner of Fort and King, McInerny’s Shoes seemed to Rachel a palatial store, with polished mahogany walls, stained glass windows, and expensive Chinese rugs on the floor. The plush upholstered chairs in which customers sat to try on shoes were nicer than any Rachel had ever seen in anyone’s home! But when she asked if James, Kimo, Kalama still worked here, no one in the store recognized the name; and one older gentleman went so far as to assert that he couldn’t recall anyone by that name ever working here.

She had even less to go on in tracking down Ben. Papa had said he was a boatbuilder in Kaka'ako, but a walking tour of the docks there yielded no shipbuilder who had ever employed or apprenticed a Benjamin Kalama.

Broadening her quest beyond the immediate family she combed the telephone book for Mama’s brother Will or his son David. She found neither, but did stumble across a familiar pair of names:

Kiolani, Elijah and Florence, 1901 Ulewele St

. Her pulse quickened at the discovery: Aunt Florence—Papa’s sister—and Uncle Eli! It was a different address than the one she remembered, but it had to be them, it

had

to be. Excitedly she sought out Ulewele Street and was soon standing on the doorstep of a neat little saltbox house with the name

Kiolani

stenciled on the mailbox. Beside herself with anticipation, Rachel rang the doorbell and waited as, inside, footsteps shuffled slowly to the door. It was opened by a woman in her eighties, white hair stark against brown leathery skin. Rachel gasped. It was

her

, it was Aunt Flo who made the best

haupia

pudding anyone ever tasted, smiling pleasantly as she said, “Yes?”

“Aunt Florence?” The woman looked at her blankly. “Aunt Florence, it’s me—Rachel. Henry’s daughter.”

The smile vanished from Florence’s face, replaced by a scowl. “Not funny. Rachel dead, long time ago.”

Rachel laughed. “No, I’m not. Look at me, Auntie, it’s Rachel, I’m back from Kalaupapa!”

At that word, the old woman flinched.

“Rachel?” she said. Her voice was soft, and the realization in her eyes not a dawning but a darkening. “Oh my God, baby. Oh my God.”

“They released me, Auntie. I’m cured!” She felt tears running down her cheeks. “I can’t believe I found you! I’m so happy to see you!”

Florence’s gaze swept up and down the street, then back to Rachel. She took in Rachel’s clawed hand and a look of distress spread across her face. “Why do you come here?” Florence asked, and now even Rachel could see the black blossoms of fear in her aunt’s eyes.

“You’re my

'ohana,”

Rachel said as if it were the most obvious thing in the world—and Florence flinched again because it was.

“Baby,” she said softly, “you know after my brother Pono got sent to Kalihi, we took in his family; you know?”

“I know,” Rachel said.

“The Board of Health, they send people out all the time to check on Margaret and the

keiki

. Bring ’em to Kalihi to test for

ma'i p k

k . Then they start testing me and Eli and our

. Then they start testing me and Eli and our

keiki

. They tell our neighbors, ‘These people have relatives with leprosy.’ Nobody wants to go near us anymore. People break our windows, they say, ‘Go Moloka'i where you belong!’

“Somebody from the Board of Health goes to Eli’s job, tells his boss that Eli’s brother-in-law, his niece, are lepers. He loses his job, just like that.” The memory was still vivid enough to make her wince. “Never once any of us tests positive for leprosy. Never once! But nobody cares. Eli gets a new job, then somebody tells somebody else about you and Pono, and no job anymore. Soon we can’t afford to take care of Margaret and her

keiki

. They go leeward side, where nobody knows them. Never come back to Honolulu. Margaret dead now.”

Florence reached out, touching her hand gently to Rachel’s cheek. “Took years before everybody forget about the

ma'i p k

k . Nobody here knows. Nobody.” She glanced around as if afraid people were watching even now, watching and judging. “Go ’way, baby,” she said softly, sadly. “I’m sorry. Please, go ’way.”

. Nobody here knows. Nobody.” She glanced around as if afraid people were watching even now, watching and judging. “Go ’way, baby,” she said softly, sadly. “I’m sorry. Please, go ’way.”

Slowly but firmly she closed the door on her niece.

If with a thought Rachel could have ended her life in that moment, she would have gladly done so. Denied that mercy, she was forced to walk away from her aunt’s house with an even heavier burden than she had arrived with.

Somehow she managed to find the bus stop and stagger home, if that was the word, and into bed, where she cried herself to sleep as she had that night aboard the

Mokoli'i

, her family having been left behind on the shores of O'ahu.

She made no further attempts to contact her family for weeks, instead bearing down on the unpleasant but necessary task of finding a job. But the difficulties were similar to those she encountered looking for an apartment. If she listed her work experience at the Kalaupapa Store and Bishop Home she was announcing herself as a Hansen’s disease patient, and the employers inevitably hired someone else. But if she didn’t list them, she seemed to have no prior work experience and that didn’t help her prospects either. She applied for positions as a grocery store clerk, waitress, hotel maid, cook, seamstress, and cleaning woman; but she was competing in a crowded postwar job market and failed to land any of them.

Her room was nowhere as nice as her cottage in Kalaupapa, but after a few weeks of hard work and some new curtains, it had become quite livable; even cozy. And it had one thing the house on Moloka'i didn’t: a world outside its doors. Within walking distance there were movie theaters, concerts, museums, bookstores . . . already Rachel had found two Jack London books she didn’t have for a mere 25¢ apiece! She was getting to know her neighbors and the local merchants, starting to lay the foundations for a new life; and if this wasn’t the Honolulu she’d grown up in, it was the only Honolulu she had.

Two separate but similar pieces of mail arrived within days of one another. The first was from the United States District Court, family division, notifying her that a date had been set for the hearing regarding her daughter’s adoption papers and that she should show up at nine A.M. on the morning of June 9, 1948.

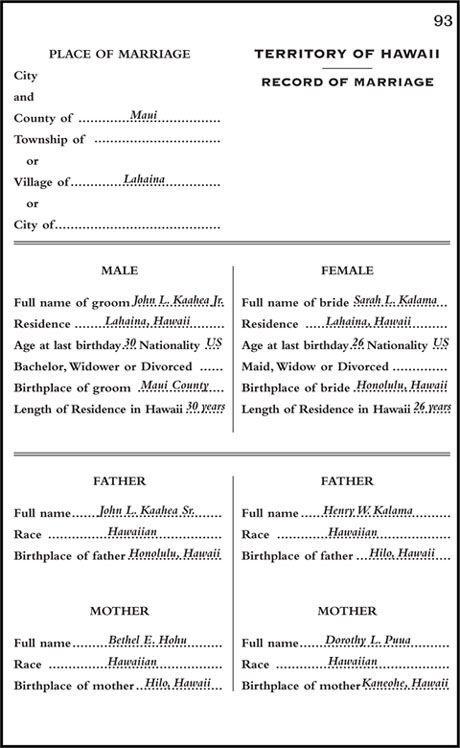

The second envelope also bore a government address, this one from the Territorial Department of Public Health. She opened and unfolded a pale photostat of a marriage certificate.

How could such a simple document—a standardized form, an artifact of

haole

bureaucracy—engender such awe and terror as Rachel felt now? She had not a doubt that this was her sister’s marriage certificate; her parents’ names jumped out at her. The document went on to note the name of the person issuing the license, as well as the witnesses to the ceremony, including one Dorothy L. Kalama.

Almost before she realized she was doing it, Rachel’s left hand had picked up the phone and she was using a pencil held in her crabbed right hand to dial the operator. She requested a phone number for a John and Sarah Kaahea on the island of Maui; and when the operator replied, “I have a Sarah Kaahea on Waine'e Street in Lahaina,” Rachel thought her heart would burst. She cradled the receiver between chin and shoulder and with her good hand scribbled down the number—LAH 7939—and asked the operator for the address, jotting down

633 Waine'e

Street, Lahaina.