Moon Called (9 page)

Authors: Andre Norton

Before the girl could answer, Thora turned and pushed past the screen—making for the outer chamber of the house. She heard a low murmur of voices and then she was into the lamplight of that first chamber. On the matted floors her hide boots made little sound. She had been so accustomed to walking with care that she was well into the room before Makil paused in mid-word to stare at her.

Malkin was still curled against him, by the look of her in deep sleep. His face was drawn into harsh lines but there was still about him an air of determination and purpose. Martan was gone, but a much older man leaned forward in a second chair, his closed fists on his knees, his position tense, urgent.

Upon Makil’s sudden silence this one turned to look at Thora, a frown fast forming on his broad face. But he got to his feet, asking in impatient

voice:

“How may we serve you, Lady?”

She eyed him for a moment before she answered. This was one who held authority. She had seen men with this air among the traders—or even among her own people when the Hunter ruled. Plainly he was just such as she sought.

“I am not the Lady,” she returned coldly, “but one of Her Chosen. As to how you may serve me—let me go on my way. This is no land for me.”

He looked surprised, more surprised than Makil who also watched her intently. The elder man’s hand moved in a swift sign Thora knew—or it resembled one she knew. In turn she gave the recognition, one which a Chosen would use to an equal. Full belief or not, these people still held to some remnants of the Faith and thus must be recognized as distant kin.

Now the stranger spoke. What he said was garbled to Thora, the wrong inflection here and there on one of the sacred names—still it was understandable enough that she could make the required answer of ceremony.

“

She

is the beauty of the green earth, the white moon among the stars.

“To

Her

hand lies the mysteries of the waters, of the earth’s growth, of the wind which caresses, of that which drives the storm.

“From

Her

all things proceed, to

Her

keeping

all things return.

“Let there be beauty and strength, power and compassion, honor and humility, mirth and reverence, where

She

walks!”

Thora narrowed her small power, honed it to sharpness, stared into the open air between them, then hurled all the force she could summon. For she must show this one who and what she truly was.

There was a trembling in the air, as if something invisible fluttered there. Then there formed, for only a short instant, the sign which she wore on her inner girdle. It flickered into life and was gone again at the wink of an eye, leaving her weak and trembling with expended effort.

The valley chief gave a sharp-drawn breath. Malkin stirred, uttered one of her hissing cries, her red eyes opened, to shine coal bright.

“It would seem,” Makil broke the silence first, “that there

are

others, who do walk the same Way. Do you accept this now, Borkin?”

The man was still staring at the place where the sign had appeared and vanished. Now he nodded slowly.

“One must accept the evidence of one’s eyes. Who are you who can summon that?”

“I serve

Her

, being born into that service—though I am not a full initiate. There was an end to my people before I could become a vessel of full power. But

She

has favored

me since so that I can call upon what little I know and it does not fail me.” Let him at once understand that she had limits, Thora decided. She must make no claims, which in days to come might be proven false.

Again Borkin spoke, some words clearly, some so twisted she did not know them for sure. Only what he voiced were sacred things. Though to say such thus openly—before Makil—she wondered at this desecration of what was to her private matters, only to be spoken of in the shrine, and there at the proper time. When he had finished she replied firmly:

“I know nothing of your customs. If you are the Hunter for your people then it is true you should know this. But it is not fitting that you speak openly—out of proper place and time.”

Borkin looked startled. “This is,” he swung back to Makil, “the ancient learning! These people have followed the pattern as it once was!”

Malkin slid down from Makil’s lap and came pattering across to Thora, reaching up to catch the girl’s hand which she held close to her own down-covered cheek.

“Do you doubt now?” Makil asked. “The sister-blood can tell—”

“But it is against—”

Thora carried the battle into his own territory. “Is it against your custom that a woman should know such things? Well, to me, it is against propriety that any man should say certain

of the words you have just uttered. Hunter you may be, but in our Shrine even the Horn-Crowned does not summon without due ritual, deferring always to the Three-In-One.”

Borkin gave an impatient wave of the hand. “It is enough for now that we do understand the same power. That you have it at your call is good. For this is a time when every road which leads to the Light must converge and our strengths added to strength, lest we be found wanting when the Dark rises—and rising it is! Do not mistake that!”

“You have already seen some of their handiwork,” Makil’s tone might not be so vehement but it was none the less insistent. “You found the body of Samkin—”

Malkin gave a small cry which might be one of mourning. While Borkin took an impatient stride down the room, then back again.

“Samkin, yes—but what of Karn?”

Makil shifted in his cushioned chair. “He is not dead. That we would have known—”

“Where he is perhaps death would be better! We can trace his life force—yes, that still burns. But where have they hidden him? What use will they make of him? That we cannot tell—”

“Unless,” Makil leaned forward, his eyes on Thora, capturing her gaze and holding it as

if he summoned will to bend her to some service.

“Unless,” he said again after a pause which seemed to stretch uncomfortably long, “your

power, Chosen, being different in some ways from ours, can provide some answer—”

“What would you have me do?” She had no mind to be drawn into any affair of theirs.

“Our comrade Karn, with Samkin, his blood-brother, was sent on a scouting mission. In some way they were both entrapped. You found Samkin, my blood-sister has told me that. We have Karn’s candle burning in the sanctuary. It has not gone out, thus he still lives. But in the direction he went there is now a wall of the Dark. Therefore we know he is held by the sons of Set. They can learn from him what we seek—”

Borkin took up the argument now. “And perhaps

that

is what you have already discovered, Chosen—that storage place of the past. Those of Set sought it once. But their leader died in the seeking. Malkin has told of the body you found; therefore we may surmise that either he and his people came upon that place by accident—or all those knowing of it died with him. That such places exist are old tales. The Elder Ones made safe holds against the coming of Days of Wrath. Two we have already located. But one was partly destroyed and what it contained was beyond claiming. We must have more—enough so we can bring against the Dark great force. For our numbers are few and we cannot stand against their hordes hand to hand, weapon to weapon.

“This hidden place which Malkin believes

you and she can find again—perhaps that which lies within cannot be mastered by us. But in any event it must not be left to the enemy. Just as Karn, living, must not remain in their hands. For they have ways of binding the spirit, and it may be, having wrung him dry, they could fill that emptiness with an evil brew of their own devising and send him against us—his kin! They

have

done such things—”

9

Thora stood very still. It was as if a wind from those snows still salting the peaks above had curled about her. What he had said was part of ancient and terrible legend—a story at the Craigs. Whether such a monstrous crime could indeed be, Thora did not know—but that Borkin believed it fully made an impression she was unable to push aside.

Only neither was she ready to be drawn so easily into the affairs of the valley people. That one of their blood had been taken, yes, that was a dreadful thing. But it was

they

who were kin-bound to the missing. She had taken no vengeance on those who had plundered the Craigs—for that was not the Lady’s way. SHE punished in her own time. To use power as a

weapon—no! No wonder these two had traveled so far from the true beliefs!

They must have read a part of her thought in her expression for Borkin’s scowl grew darker while Makil—with him it was as if the natural warmth of the man had withdrawn. She had a fleeting memory of him as she had seen him in her vision—the master of the sword’s flame. That was not this man.

“I cannot use any talent I have,” she said slowly, “to summon power, save as the Lady works through me—and never to my own use. I do not think that you truly know HER as She is—”

“So—what will you do now?” Makil asked, his voice remote, coming to her across some chasm.

“Go forth from this valley and be about my own concerns.”

Borkin smiled, no pleasant smile. “That we cannot let you do.”

She was so startled by that for a moment she simply eyed him unbelievingly. A Chosen could not be so ordered—certainly not by a man!

“What then would you do to keep me—bind me with cords?”

“If the need be—yes.”

Her hand fell to knife hilt. She could not accept that he would dare any such thing.

“Do you not understand?” Makil asked. “We have good reason to believe that we are under

the eyes of the Dark. If you go forth from here on your lone now you would be easy meat for those who serve the Shadow. Karn was guarded, not only by a warrior’s skills, but by armor of spirit—still he was taken. You have already crossed the land they claim. Who can tell what you have roused there? Traces of Power passing can be read by those trained in such trailing. They would come seeking you—”

Her hand dropped from the knife hilt to seek the gem beneath her clothing, pressing that into her flesh, as if to make it a part of her. It was true that one with Power, even as little as she believed hers to be, could sense it elsewhere. Just as she had found it in the forgotten oak wood. Had she left traces of her passing so—to be picked up by the Dark? Had perhaps that shameful cloak they had hung upon the dead tree served as a beacon?

There was a touch on her hand. Thora started, looked down at Malkin. Then she remembered that some of the furred one’s blood had also passed her lips, making her free of that strange barrier in the wood.

“Just so,” Makil said deliberately. “You say you are apart from us—yet the Blood Sister made pact with you. You are one of us after all.”

Thora raised her other hand to rub it furiously across her lips, trying so to banish memory—the certainty that perhaps what he

said was unfortunately true. She could not walk away as she wished—

Makil’s face was very strained, deep shadows lay beneath his eyes. He slumped among the cushions bracing him in the chair as if he had come to the end of his strength. Borkin uttered an exclamation and went to him, while Malkin whirled away from Thora, leaping to capture both of the young man’s hands, hold them tightly to her small breasts. He appeared to rouse, speaking wearily to Borkin:

“Let her rest within the outer Sanctuary. She must be with us in spirit or she cannot stand with us at all.”

Borkin glanced over his shoulder to the girl. There was very little softness in that look—rather it measured her, put her on the defensive. Then he said only one word:

“Come!”

Sara appeared in the doorway to the inner rooms, hurried to Makil even as Borkin pushed open the outer portal, sweeping Thora with him. She found she could not protest as she went, Kort close beside her.

Through the edge of the village they passed, then turned into a path which was marked at intervals with standing stones. These were studded with crystals which gave a faint light like that of distant stars.

Borkin strode so swiftly that Thora’s strength was further taxed. Still pride would not allow her to lag in such company. The road

of the stones curved upward through the fields, still it did not draw too far from the lake—and now those stones were set closer and closer together.

She was aware that they were treading into what must be the heart of a great spiral. Farther and faster Borkin went and she followed with Kort. About this place hung a heavy silence. The night birds, the insects, of which she had been aware when they left the village, were now silent, or else all kept their distance.

Her jewel was warming. Power—yes, here was power—as yet unawakened, slumbering—but still to be sensed. And she was attuned, in spite of her denials concerning these men. There was a kinship between what she carried and a greater force abiding here.

They reached the heart of the spiral, entered from between what was now solid stone walls into an open space. This was circular and the stones guarding it gave off an even greater light. Borkin beckoned the girl forward. Reaching forth his hand he brushed fingertips across the front of her jerkin at heart level. She did not, could not, deny that he was truly an adept of the Mysteries, certainly with more power than the Hunter. Though she told herself fiercely—not the equal of the Three-In-One after they had called down the power. He sing-songed words of ritual, and to those she made her own answers.

He was, she sensed, striving to introduce

her to some force outside her own time and space—to powers which she had never dared call upon, nor would she know how. For such was granted to the Chosen only when the Lady ordained. Thora fought receiving at the hands of this stranger what she held to be the rights of her own kind.

Yet from that slight touch of his there came an inflowing of energy—which, resent it though she might, Thora could build no defense against. Borkin pointed to the pavement which was now glowing silver-white and from which a haze was rising, as might the traces of smoke from a fire of well-dried wood.

“You may try—” she removed her hand from her hidden gem. “but my power—the Lady—” She paused. No, she would offer this man no argument. Why should she? Let him see that she could not be bent in any fashion—that within herself she held defenses against what he strove to bring to life.

He did not answer, only turned from her as if his part in this act was completed. Thora watched him go. Then, because she was so tired that she could no longer pretend strength where it was not, she sank to her knees, settling cross-legged. While Kort paced slowly about the circle, his head up. Though there was something of uneasiness in his movements, he gave no direct warning, only his tail swung steadily from side to side, his lips drew back to show fangs, his eyes

gleamed.

The haze about her was deepening, growing thicker. There was a pulsing surge in its rising—ebbing, flowing. She discovered that she was breathing in time to that, deep breaths which carried air into every crevice of her lungs.

Now the moon gem was so warm that it was too hot against her skin. She brought it forth, held it cupped in her hand, looking down into the surface. There also the radiance flowed. The jewel itself appeared to grow larger and larger. She was no longer aware of holding it in her hand—rather it was a vast bowl of light.

Thora sought to speak the rituals she knew, to divorce and defend herself against the ensorcellment happening. She MUST stand apart—not be encompassed by the power here. If it were meant to fill the one who sought this shrine she was not prepared to give it room. Rash assumption of power could blast the reckless. Still she was caught, and from this trap there was now no escape.

Under her feet stretched a narrow trace of way. In the dark gloom of this place it shone with the silver bright of the Lady’s touch. On either hand walls stood tall, dead black as a clouded night when not even a star gleamed. From those walls came a steady beat which was like the regular pulsing of a giant heart. The earth where she now walked might itself be a living creature, lying in wait—for what

Thora could not tell.

The girl looked up, setting her head far back to catch a gleam of sky with star, if there was such here. But all she could tell was that the walls did end—well above. A wind blew about her, and that was like a puffing of breath—though it was both sharp and chill.

On she went because there was laid upon her a command she could not disobey and her faint fear subsided. Rather she sped her steps with a growing excitement, knowing a need to reach whatever nameless goal called her.

Still the path ran straight and she walked it, the walls tall beside her. There was no change in this half-alive world into which she had been wafted—or summoned. Only there was a need which she must assuage, though the manner of that service was still hidden from her.

Her feet hardly seemed to touch the ground, it might be that her will alone, or that which had sent her, bore her forward—the walls skimming past. Thus, at length, she came abruptly forth from that silt. In her now the beat of the great heart was so attuned to her own that it strengthened her. There was no fatigue of body, no stiff ache in her limbs. She was tireless.

The country into which Thora advanced was sharply etched in a strange fashion, degrees of dark, some more, some less, marked its features. Some splotches tossed branches as she was borne by them. The silver trace on the

ground had vanished abruptly upon her coming into the open. Yet there was still a trail—

Thora shaped an impulse born of her will, centering on the land ahead—questing—drawing upon all she could summon. Now there sprang up on the black of the earth faint traces of silver, these shaped like the prints of naked feet. She hovered over them, unaware any more of her own body, coasting above the surface of the ground where they were set. Each was apart from the next as if they measured the stride of a man walking steadily, with a purpose. Following them she spun on into heavy darkness.

The girl was no longer aware of the heartbeat, but her excitement grew as she longed for clearer sight, a better knowledge of the land she traveled. On ran the footprints. He who had left them might have been sent to march across the world unendingly.

Thora wanted to be done with trailing—to come face to face with what lurked in this dark world. She hurled herself on, whipped by that desire.

Since the ceasing of the heavy beat, this had become a silent world. But now she became aware of another sound. Those wind-tossed branches did not sigh nor rustle, there were no calls of any bird or insect. Only, from afar, came a thump which was not that of the heart she had sensed as one with her. No, this was a drum beating with a sharp tap which stirred

through the velvet darkness until she could believe its harshness made evil patterns in the air. And that troubling awoke once more her fear so she could no longer skim along, trusting the country. Rather she peered at every clump of the black, waiting for something to rise from ambush.

The dark land was coming alive, bringing alarm and the stench of peril. Now the wind carried the rotten sweetness of decay. There was death—or something worse than death ahead. Thora could not retreat, for it was toward that center of evil the footsteps she must follow marched so resolutely.

Rising from the black plain was an even denser mass—if there could be gradations of black. In this place the girl discovered that the very negation of light did possess subtle changes. The mass ahead was too regular in shape to be a hillock—nor was it a forest—

From within it came that clamor of drum or drums. The sounds they gave forth became one deep voice crying aloud, a second higher in tone, answering, with now and then a sharp rattling.

Into that mass the tracks disappeared. And into it, Thora, unable to control her going, flew after. There was an utter and complete lack of all sight for a long moment. She was stifled, buried, gasping—as if she had been flung, helpless, into a pit in the earth with sour soil heaped above. Her heart fluttered, pushed

with effort, to keep life in her.

She burst out of that dark into a blaze of light which seemed blinding. At the same time the stench of old evil choked her, and a pain she could not understand made her writhe. Her answering scream was suppressed, she lacked the power to loose sound from her throat. Thus she hung in torment until she sensed that this was an assault, not upon her body (if she still had one), but rather on the core of life within it.

There came into her mind, raggedly and at first without her conscious will at all, the things she had learned. Her defenses stiffened, so slowly that she might be building a wall, stone by patiently laid stone. Still she fought and at last surrounded herself with a sphere of hard-held power. It was not enough merely to weave that for her protection—she must reach out beyond that—So had she been sent here to do.

Thus, as if she did have eyes which had to adjust to the glare after the long dark journey, she looked about her. She might be swimming in a sea of blood, for about her was a scarlet haze as thick as a fog. There were no prints to guide her. Only that faint pull. Very warily she allowed herself to be drawn along. She sent forth a probe—

Whatever she must do here must be quickly accomplished, for the threat grew ever stronger, pressing in upon her hard-held armor.

To seek at the same time weakened her even more.

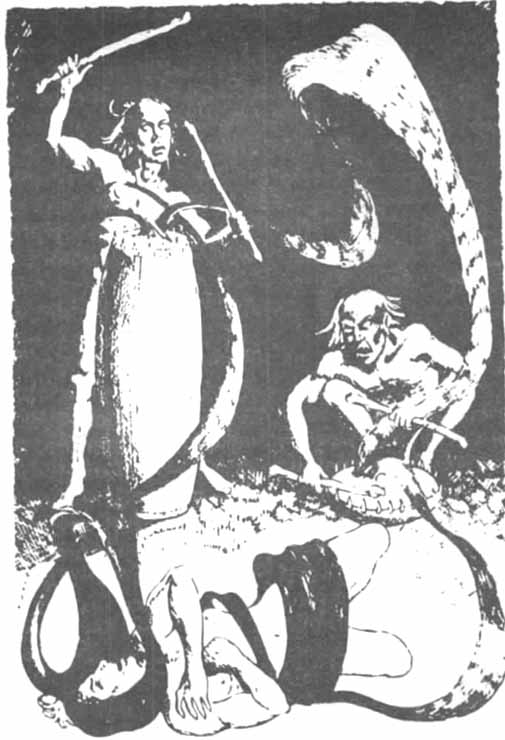

She followed the probe. The mist thickened and the chatter of the drums was savage—a pain through her whole person. Down in the heart of that mist shown a spark—the sign of another life force. That—that was the goal towards which she had been drawn. She gathered her strength, flashed towards it.

It was as if she looked from a high window into a cavernous room. The outer limits of its walls were so far removed they were totally hidden. But directly before her was a sharpetched scene, vivid and alive.