More Bones (7 page)

Authors: Arielle North Olson

The blacksmith hurried from the castle, happy to escape with his life. He knew the baron would have pulled forth his sword and murdered him if there had been so much as a scratch or a dent in the shiny metal.

The baron loved his new armor. He might have thought otherwise if he could have foreseen the future. But he was imagining how ferociously he could fight, protected by the sturdy metal. He could hardly wait to get into bloody battles, but first he had to gather everything he needed for going to war.

That very night, he left his castle on horseback, riding down the steep road to the peasants' huts. He pounded on their doors. “Give me all your money,” he thundered, “and I will free you from future rents.” Now the peasants knew the baron never kept his promises, but most were too frightened to resist. If they argued, they lost their lives.

When the baron rode off to battle the next spring, he was wearing his shining armor. The peasants watched until he disappeared around a curve in the road. Then they hugged one another. Some cried with relief. Others danced in the fields.

The peasants felt as if a black cloud had been lifted. They dared step outside their huts at night. No men were found hanging from tree limbs the next morning. No maidens or small children disappeared into the castle, never to be seen again.

Years passed. The walls of the baron's mighty fortress were not maintained. Water leaked through holes in the roof. Some of the heavy beams began to rot. But the peasants were happyâuntil one terrible day when the baron came riding home.

It was obvious that his temper had not improved while he was away, nor had his fortune. He whipped the peasants for neglecting his castle and demanded that they pay rent for the time he was gone. If they could not pay him, he set fire to their hutsâusually at night. That's when he liked to ride about the countryside, spreading terror wherever he went. The peasants appealed to the king, but the baron ignored the royal decrees and killed the royal messengers.

When the peasants began to revolt, the baron just laughed. But his night rides turned sour. There seemed to be a peasant hiding behind every tree, hurling rocks at him before melting away in the darkness. The baron decided to wear his armor day and night. Finally he shut himself up in his stronghold and stationed guards at the entrance. But still he underestimated the peasants' anger.

One moonless night, a band of peasants managed to scale the treacherous cliff at the back of the castle. It was unguarded, because the baron believed that no one could approach from that side. The peasants crept toward the front, waiting in the shadows until the guards fell asleep. Then they overcame the guards, set fire to the drawbridge, and threw burning torches into the castle. It was a terrifying sight. Flames leaped high, turning the great stronghold into smoldering ruins.

Many of the servants managed to flee, but the baron was not among them. The peasants were uneasy. They wondered if the baron could have escaped the flames. If he had, he would be eager to kill them.

No one went near the castle for days, but when the embers cooled, a few brave men made their way into the ruins. There they found the baron. But not where they expected him. He was hanging from a charred beam in the great hallâdead. He was wearing his armor, with the visor closed.

The peasants were stunned. Did the baron's servants find him overcome by smoke on the night of the fire? Did they hang him to make sure he never whipped them again?

The news spread quickly. But none thought the baron deserved a decent burial. So he was left there for months, swinging in the wind until one wild night, a bolt of lightning flashed through the armor and knocked him to the floor.

When the storm moved past, peasants were startled to see an eerie light moving through the ruined castle. It continued out to the ruined stable, rising to the height of a man on horseback. Then it came bobbing down the hill, closer and closer. The peasants rushed into their huts and bolted the doors. When they heard hoofbeats and the clank of spurs, they dove into their straw beds. But nothing could protect them from the ghostly horse and rider. Once again, terror filled their nights. Huts were burned. Men, women, and children disappeared. The baron was far more cruel dead than alive.

The frightened peasants went deep into the forest to ask an old hermit for advice. He told them they needed garlic. “Chew it. Mix it with spittle. Add salt if you have it.” The peasants were confused.

“Climb into trees that lean over the roadâand when the baron rides by, spit on his armor. Not once, not twice, but three times. Mark my words.” The peasants were even more confused. “You'll see,” said the hermit.

Entire families hid in trees at night, spitting down on the baron. He didn't seem to notice. But as the peasants watched, the eerie light surrounding the armor began to fade. The shining metal started to rust. In a matter of weeks, the glow was gone.

Then one night the baron slid out of his saddle and tumbled to the ground. His ghostly horse disappeared in the mist. Before he could struggle to his feet, peasants dropped from the trees and threw chains around him. The next morning they hauled him to court. Imagine how fearful they must have been!

The judge was trembling when he asked the prisoner his name. There was no response. The judge asked again. The baron didn't answer. The judge began to get annoyed when the baron refused to speak a third time. He said, “Open your visor.” Still the prisoner stood defiantly before him.

Finally a brave peasant rushed over. He pried open the baron's visor and screamed in horror.

There, inside the rusty helmet, was . . . nothing . . . absolutely nothing. Yet still that empty suit of armor was flexing its fingers and moving its feet.

The judge choked out his verdict. “I order you to be hanged at dawn.” But the peasants objected.

“That didn't kill him before,” one cried. “Take him to the blacksmith's forge. Turn him into . . .” and here he faltered.

“A bell,” said the judge. “If he's a bell, he can do no harm.”

But it was almost as if the blacksmith had been sentenced as well. When he hammered the armor, it groaned and writhed. When he thrust it into the smelting furnace, it shrieked and reached out to grab the blacksmith with fingers of hot metal. Lightning streaked out of the furnace, and thunder almost deafened him.

The blacksmith thought he was losing the battle, until suddenly he remembered the hermit's advice. He grabbed a clove of garlic, tossed it into his mouth, and chewed on it. Then he spat at the molten metal, once, twice, thrice. His spit sizzled and turned into steam. But he finally subdued the armor and made it into a bell.

The bell was hung in the marketplace, so the peasants could see that the dreaded armor would no longer stalk them at night.

But the very first time the bell was rung, it cracked and spit out a shower of sparks. The peasants backed away, whispering to one another. Was the ghost trying to slip out the crack? Or would it haunt the bell forever? No one knows . . . except for the baron.

The Gruesome Test

JAPAN

Â

Â

Suitors came from all over Japan to woo a beautiful maiden. First they fell in love with herâthen they ran away. Some were heard screaming as they raced down the road.

Â

Suitors came from all over Japan to woo a beautiful maiden. First they fell in love with herâthen they ran away. Some were heard screaming as they raced down the road.

Suspicious neighbors spread rumors. They suspected that the maiden might actually be a goblin or a fox-woman. Her parents were mystified. Why did their lovely daughter terrify young men? She was gentle, happy, and hardworking. She didn't complain when helping her mother around the house and never wasted a single grain of rice when she cooked their meals.

What more could parents desire? Grandchildren. That's why the couple wanted their daughter to marry. Besides, the aging father needed a strong son-in-law to help him grow riceâand he needed him soon.

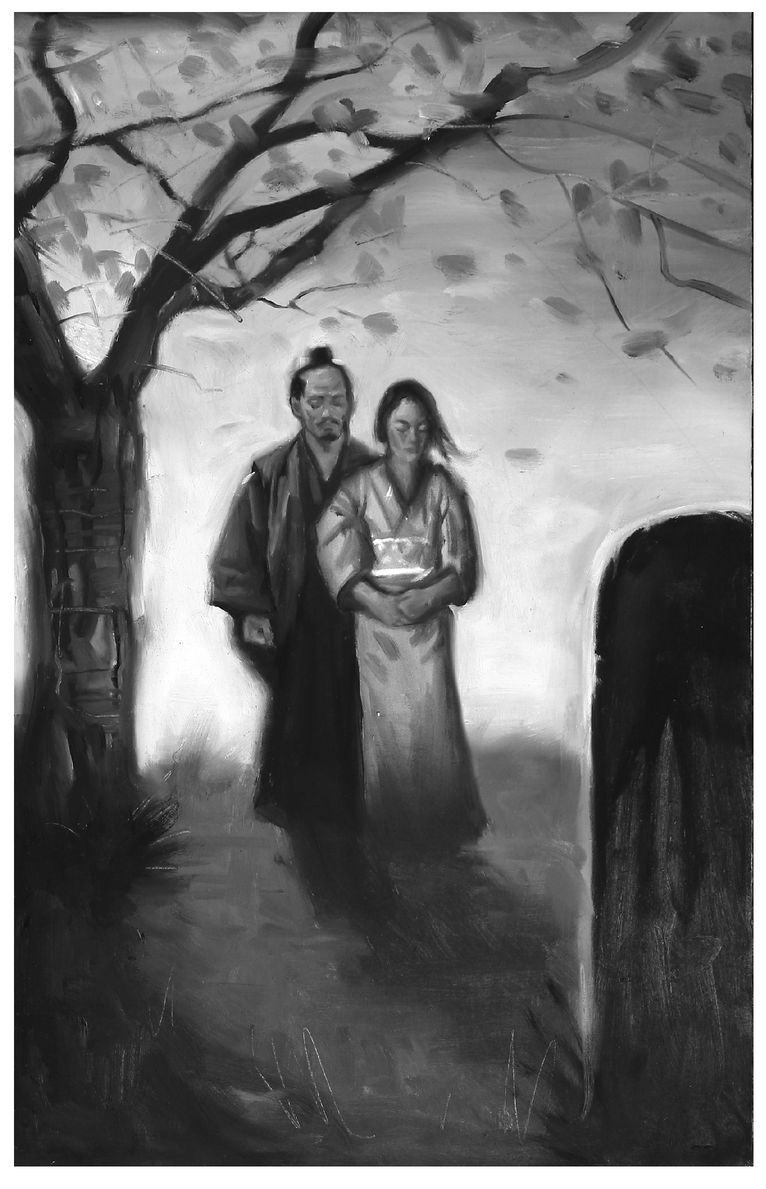

Arranged marriages had been the tradition for as many generations as anyone could remember. But long ago the father had decided to let his beloved daughter choose a husband for herself. One spring he began to regret his decision. He sat beneath a flowering cherry tree, watching pink petals fall to the ground. Would his daughter's youth fade away as quickly as the delicate flowers? Just as he was losing hope that she would ever marry, a soldier came striding up to the house.

“May I court your daughter?” asked the bold young man.

The father liked his broad shoulders and muscular arms, good for planting rice. “Come right in,” he said, and he happily introduced the young man to his daughter.

The maiden moved gracefully about the room, serving the soldier tea and rice. She seemed shy, speaking softly and lowering her eyes. The young man seemed smitten. When the meal was over, she accompanied him to the door and quietly invited him to come back.

“But not until midnight,” she whispered, “and knock lightly so you do not awaken my parents.”

He was surprised, but not half as surprised as he was when he returned that night. The moment he entered the house, she made a very strange request.

“You must promise on your honor,” she whispered, “that you will submit to a test of your love for me. And promise that you will never tell a living soul what that test is.”

The young man couldn't imagine what the maiden had in mindâbut he agreed to remain silent. “On my honor, I will never tell.”

“Then wait here,” she said. She slid open the paper screen to her room and closed it behind her. The soldier waited impatiently. When she returned, she was wearing a loose white garment. Oddly enough, the handle of a shovel poked out from under the hem.

“Follow me,” she whispered. They moved through the village under a cloudy sky, with only fleeting glimpses of the moon. On such a night, ghosts were said to wander. The soldier followed the white figure ahead of him, careful not to awaken sleeping dogs. They slipped through the village streets to the woods beyond, hurrying down the dark road until they reached an ancient cemetery.

When the moon emerged from the clouds, they could see old gravestones covered with moss and mold. Here and there, bamboo cups held wilted flowers. Weathered statues of gods stood guard, protecting souls.

The maiden stopped by a grave that looked quite fresh. She pulled forth her shovel and began to dig, flinging clods of dirt to one side. Then she dropped to her knees and swept aside dirt with her hands. The soldier could see that she had uncovered a small coffin.

Imagine his surprise when she lifted the lid, opened the white shroud, and tore an arm off the corpse inside. Then she clamped it in her teeth and took a large bite.

“If you love me, you will eat what I eat,” she cried, ripping the other arm off the corpse and tossing it to the soldier.

He didn't hesitate. He took a large bite himself. Now he was even more surprised. He was eating a candy corpse, made of sugar and rice flour.

The maiden burst out laughing. “You are the only one of my suitors who did not run away. I want to marry a brave husband, and you are the one.”

You would think that the soldier would laugh, too. The maiden was not a monster, after all. But he glowered at her. “Only candy!” he said. “I thought you were giving me much more.” He grabbed her shovel and began to dig up a real grave.

This time it was the maiden who ran away screaming.

The Enchanted Cave

SPAIN

Â

Â

Peregil didn't Need the moonlight to find his way to the ancient well. The water carrier and his faithful donkey had trudged up the steep path thousands of times to fill their earthenware jugs with water. Usually they didn't work this late, but the night was hot, and thirsty townsfolk were still in the streets. “Perhaps I can sell another jugful,” Peregil told his long-eared companion.

Â

Peregil didn't Need the moonlight to find his way to the ancient well. The water carrier and his faithful donkey had trudged up the steep path thousands of times to fill their earthenware jugs with water. Usually they didn't work this late, but the night was hot, and thirsty townsfolk were still in the streets. “Perhaps I can sell another jugful,” Peregil told his long-eared companion.

They entered the abandoned fortress that rose high above Granada and proceeded to the well. The great battlements of the Alhambraâwith its watchtowers, fountains, and elaborately decorated roomsâhad been built centuries earlier when Moors ruled that part of Spain. The wells they had dug were as impressive as their fortress, because the shafts reached all the way down to the purest, coolest water.

Peregil was about to fill his large jugs when he heard a feeble cry. A gnarled hand beckoned to him from a stone bench just beyond the well. The water carrier hurried over to find out what was wrong. In the moonlight he could see an old man lying there, dressed in Moorish garb. His voice was faint and raspy.

“I will give you twice what you could earn for your jugs of water,” he said, “if you will let your donkey carry me to the city instead.”

“God forbid,” cried Peregil, “that I should charge a man in such trouble.” He hoisted the Moor onto his donkey and steadied him as they moved down the path, keeping him from falling onto the rough ground. They descended so slowly that the streets were empty by the time they reached the city.

Other books

I Put a Spell on You by Kerry Barrett

Clean Break by Val McDermid

Innocence by Elise de Sallier

A Burn To Bear (Fire Bear Shifters Book 3) by Sloane Meyers

Pure Redemption (Tainted Legacy) by Hope, Amity

Tenth Commandment by Lawrence Sanders

Wild Cow Tales by Ben K. Green

I Am the Chosen King by Helen Hollick