Moses and Akhenaten (25 page)

Read Moses and Akhenaten Online

Authors: Ahmed Osman

Akhenaten's Osiride statues. These statues are two of the four colossal figures that were made to stand at the entrance of the temple Akhenaten built for his God inside the Karnak complex. They are now in Cairo Museum. In three of the statues the King is shown wearing a kilt, while the fourth, which has larger lower parts, has no kilt. This persuaded some scholars to claim that Akhenaten lacked any signs of genitalia. This proved to be an incorrect assumption; the statue is in fact unfinished, and the lower part would have been cut back later to make the kilt.

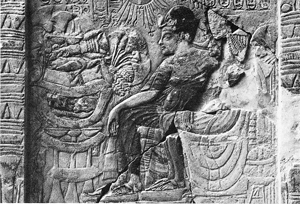

Amenhotep III and Queen Tiye. This stela was found in the house of Panehesy at Amarna. The fact that Amenhotep III is represented in a clearly realistic style at Amarna indicates that the old King was living at the time and confirms the existence of a co-regency between him and his son Akhenaten. Neither the scene nor the text indicates that Amenhotep III was dead at the time. The stela is now in the British Museum.

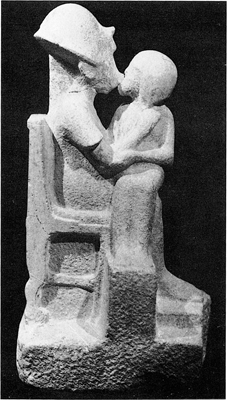

This unfinished statue of Akhenaten kissing one of his daughters was also found at Amarna. Again this was claimed by some scholars as evidence of Akhenaten's homosexuality; without any justification they stated that the younger figure represented Semenkhkare, the King's brother and son-in-law.

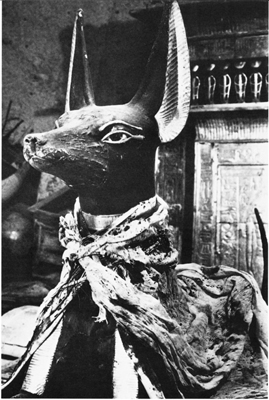

This figure of the guardian of the dead, Anubis, was found in the tomb of Tutankhamun. The jackal was sitting on a shrine containing pieces of jewellery. A linen shirt covering Anubis was dated in year 7 of Akhenaten, the birth year of Tutankhamun. The dating of Tutankhamun's birth in this manner indicated that Akhenaten was his father.

This was Fairman's first attempt to avoid the facts, for, contrary to what he said, Gunn translated the date as âYear 11' only because of the belief that Akhenaten ruled for seventeen years. He even stated this reason himself: âIn the absence of other evidence as to the reign extending beyond Year 17, no one will want to read the dating of I, plate lxiii, as “Year 21”.'

8

The hieratic sign for the figure ten is an upside-down âV' and for âtwenty' two upside-down âVs' one above the other. The hieratic docket, as can be seen from the facsimile published by Gunn, shows a complete â ' with the remains of another â

' with the remains of another â ' above it, which convinced Seele, correctly, that the date should be read as âYear 21'. But Fairman disregards that, and Gunn's statement that he read the sign as âYear 11' only because Akhenaten's reign was thought to have lasted only seventeen years in all, and goes on: âIn editing the inscriptions for

' above it, which convinced Seele, correctly, that the date should be read as âYear 21'. But Fairman disregards that, and Gunn's statement that he read the sign as âYear 11' only because Akhenaten's reign was thought to have lasted only seventeen years in all, and goes on: âIn editing the inscriptions for

City of Akhenaten,

III, Jaroslav

Ä

erný, the Polish Egyptologist, and I had hoped to include some detailed and critical study of Amarna hieratic. In preparation for this, in 1937â39

Ä

erný studied all the Amarna dockets he could find at the British Museum, the Ashmolean Museum and University College, London, in addition to several hundreds that I handed over to him. It is important to note that it was

Ä

erný's invariable method never to use or refer to any previous publication when copying and his work on the dockets ceased before he could attempt identification. His notebooks were handed over to me and I worked through them methodically, identifying all that in part or whole had previously been published. In the course of this work I discovered that the docket published by Gunn was in the British Museum (BM55640) and that

Ä

erný had unhesitatingly transcribed the date as (eleven) without a single query or note.

â

Ä

erný was unaware of the identification of this docket until after the publication of Seele's article when I informed him of the facts and asked him to re-examine BM55640.

Ä

erný not only did so, but called in Edwards and James (of the British Museum) and they all three declared that the reading was “Year 11”.

Ä

erný reported to me at the time that the docket had faded seriously, but that the hieratic sign bore no resemblance to the normal form of (twenty) and was certainly in his opinion (ten): he thought that perhaps either a piece of ink had flaked off, or that a piece of ink had fallen on the end of the sign, but the condition of the docket did not permit him to decide which. I have since examined the docket myself, and I have nothing to add to

Ä

erný's statement. In short, there is no evidence of a regnal Year 21.'

9

So, although in referring to

Ä

erný's statement, Fairman admits that âthe docket had faded seriously' between 1937â9, when

Ä

erný made his copy, and 1955 when, after Seele's article, he re-examined the docket, Fairman does not even publish a new facsimile to enable us to compare it with the earlier one made by Gunn in 1923. As if trying to avoid committing himself, he calls many other witnesses, in a way asking us to trust a group of wise men rather than giving us the evidence so that we can decide for ourselves. We have not even been told whether Fairman and his witnesses accept Gunn's facsimile, which was the basis for Seele's comments.

Even some of those who have changed their minds, such as Redford, and come round to accepting âYear 11' as the correct reading, have proved not to be really convinced by Fairman's argument: â⦠those who have only Gunn's facsimile before them will be forced to admit that the prima-facie probability lies with the reading “21”. If the present writer returns to the reading “regnal Year 11”, it is solely because of an awareness of the increasing weight of the

argumentum e silentio:

if Akhenaten did attain a twenty-first year it is inconceivable that Years 18, 19 and 20 should be entirely absent from the Amarna dockets, especially in view of the large number of dockets dated to Year 17 and before.'

10

But is this true? Were there no other records for these years? According to Fairman himself, Bennett, a member of the Egyptian Exploration Society team that worked at Amarna during the years 1930â31, was able to read the date âYear 18' on one of the ostraca he was responsible for copying. However, Fairman took the view: âBennett's ostracon of Year 18 ⦠may be dismissed as being untrustworthy, and without value.'

11

Then Fairman declares, on the following page of the same book, that âthe ostracon was not kept, but according to a rough facsimile this reading is certainly wrong'. This is even more serious, for Fairman is not telling us that the disputed ostracon was lost: he is saying that it was ânot kept', that it was thrown away. One would have expected that, as this ostracon gives an anomalous reading, it would have been guarded carefully for further examination. Instead, we now have only Fairman's judgement to rely on for whether Bennett's reading was right or wrong. No wonder Seele was convinced of a deliberate attempt by some scholars to discard any evidence that did not agree with their preconceived ideas.

However, there is still other evidence to indicate that Year 17 was not the end of the Akhenaten story. Derry has made the point: âAkhenaten is known ⦠to have reigned for at least seventeen years, a period which has been extended to the nineteenth year by Pendlebury's recent discovery at el-Amarna of a monument bearing that date and with the further possibility that this may be lengthened to the twentieth year. Mr Pendlebury has very courteously permitted us to make use of these hitherto unpublished facts.'

12

Pendlebury died a few years later without publishing the source of his information and, as with Bennett's ostracon, Pendlebury's monument cannot be found anywhere.

In the course of his article on the correct date of Gunn's facsimile of the disputed hieratic docket as being âYear 21', Seele gave a list of four scholars who believed that Akhenaten's reign lasted for eighteen years and one, Derry, who favoured nineteen. However, as long as nobody is able to discredit Gunn's original facsimile, Year 21 has to remain a certainty. As we said before, this does not mean, though, that Akhenaten actually reigned for twenty-one years.

If my hypothesis is correct, he abandoned Amarna and fled to Sinai. However, as long as Tutankhaten continued to reside at Amarna and as long as the Aten was regarded as the God of the throne, who owned the land of Egypt, Akhenaten, his son, was still looked upon as the legitimate Pharaoh. Therefore his followers kept up the practice of using a date relating to him as if he were still in power. It was only when Tutankhamun left Amarna, which soon became an abandoned city, for Thebes and Memphis in his Year 4 â Year 21 of Akhenaten â that this practice came to an end.