Moses and Akhenaten (24 page)

Read Moses and Akhenaten Online

Authors: Ahmed Osman

TESTIMONY OF SURVIVAL?

Another hieratic docket found at Amarna recorded another date that has been the subject of long arguments and has even resulted in a charge of dishonesty being levelled at certain scholars. The essence of the dispute is whether this docket refers to Year 11 of Akhenaten or â despite the fact that we know he ruled for only seventeen years â to Year 21.

A facsimile of this docket, made and published by Battiscombe Gunn, the British archaeologist,

3

persuaded the American scholar Keith C. Seele to believe that âthe hieratic date is certainly “Year 21” '.

4

He even went as far as to accuse British scholars of avoiding the evidence intentionally: âWhile the actual fate of Akhenaten is unknown, it is evidence that he must have disappeared in his twenty-first year on the throne or even later. Some Egyptologists, including the Egypt Exploration Society's excavators at Amarna, allow him but seventeen years.'

5

As many scholars all over the world became convinced by Seele's arguments, Fairman, who had been one of the society's excavators at Amarna, felt he had to rally to their defence: âIt seems appropriate to state the true position and at the same time vindicate those members of the Egypt Exploration Society's expeditions at Amarna who have been quite unjustly accused of dishonesty.'

6

Although Fairman has to be regarded as one of the most trusted British Egyptologists of this century, the way he tried to dispose of Seele's opposition makes it clear why Seele had grounds for feeling suspicious: âYear 21 occurs “certainly”, according to Seele, on a hieratic docket published by Gunn. Seele has not seen this docket, but he is quite satisfied to reject Gunn's reading on the evidence of the published facsimile. The first comment that occurs to one is that no one knowing the very high standards set and maintained by Gunn can believe that he would have advocated a reading he knew to be false simply to support a theory.'

7

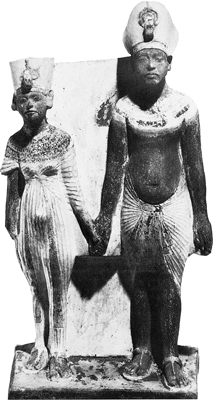

This statuette of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, now in the Louvre in Paris, offers a more realistic view of the King and Queen than do the exaggerated representations of other, more romantic styles of Amarna art. No physical defect mars Akhenaten's appearance.

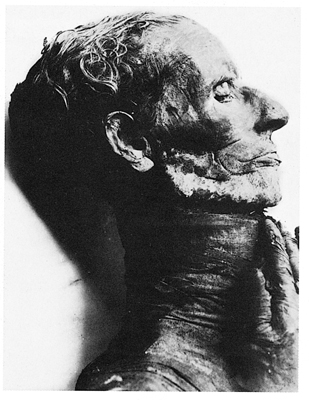

Yuya's mummy, found in his small tomb in the Valley of the Kings in 1905, now lies inside his coffin in the Cairo Museum. I have been able to identify this minister of both Tuthmose IV and Amenhotep III as the Patriarch Joseph of the coat of many colours, who brought the Israelite family into Egypt. His importance was enhanced when Amenhotep III married his daughter Tiye and made her the Queen of Egypt.

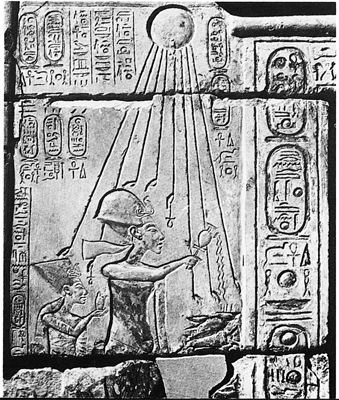

Akhenaten and Nefertiti make an offering to Aten. The royal family worshipped in the open. This scene, which was found in the Amarna house of Panehesy, the Chief Servitor of the Aten, portrays the latest symbol of the Aten, the disc at the top, sending its rays over the members of the royal family. These rays are directed at the key of life, held in front of their eyes. The name of the God (the same as that of the King) appears inside a cartouche.

This mummy of a woman, found in 1898 with other members of the royal family in the tomb of Amenhotep II in the Valley of the Kings, has now been identified as Queen Tiye.

Queen Tiye, daughter of Yuya/Joseph, wife of Amenhotep III and mother of Akhenaten. This small head of Tiye was found by Petrie, the father of modern archaeology, in the cave temple of Sarabit el Khadim in Sinai. The presence of the head of Akhenaten's mother in this remote area is one of the indications that the young king himself could have been living there for some time after he had been forced to abdicate the throne.

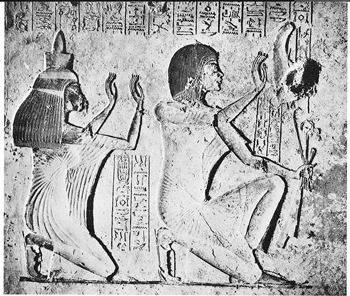

Aye (right) and Tiy. Tiy, Nefertiti's childhood nurse, also nursed Akhenaten during his childhood. She was married to Aye, second son of Yuya and brother of Queen Tiye. As the strongest military figure in Egypt, Aye protected Akhenaten's rule and helped him during his religious revolution. Aye himself became the fourth and last of the Amarna kings when he sat on the throne after Tutankhamun's death.

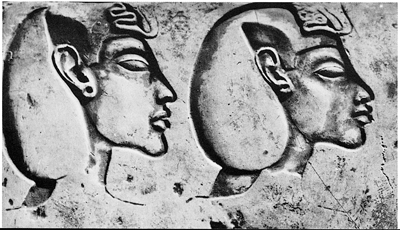

Akhenaten and Semenkhkare. This sculptor's model found at Amarna is another indication of a co-regency, this time between Akhenaten on the left and his brother Semenkhkare on the right. Semenkhkare died shortly after Akhenaten's fall from power, and it was Tutankhamun, the latter's son, who followed him on to the throne.

Akhenaten, Nefertiti and three of their children. This stela in Cairo Museum shows the royal family in kissing and relaxing mood, something that was never allowed to be shown in Egypt either before or after the Amarna rule. Scenes showing different aspects of the life of the royal family took the place of the old deities of the dead on the tomb walls of the Amarna nobles.

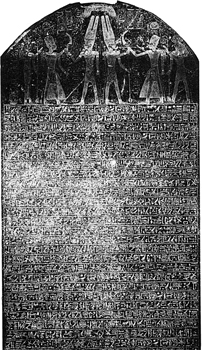

The Israel Stela. This stela of Merenptah, Ramses II's son and successor, contains the only mention of Israel in ancient Egyptian sources. Although the stela was made in Merenptah's fifth year to commemorate his victory over invading Libyan tribes, the fact that the text concludes with the mention of some already subdued nations in western Asia (including the Israeli people) has misled some scholars into believing that this king was the Pharaoh of the Exodus who followed the Israelites into Canaan.