Murder City: Ciudad Juarez and the Global Economy's New Killing Fields (36 page)

Read Murder City: Ciudad Juarez and the Global Economy's New Killing Fields Online

Authors: Charles Bowden

She has those lush lips, that long hair and fair skin. She can never be important. She is not the drug industry, she is not free trade, she is not national security.

She is the blood and dreams of a people.

I will never forget her.

Just as she will never be remembered.

Afterword

At one point, I was

hanging around Palomas, a border town an hour or so west of Juárez, and near Palomas is Ascensión, where an ice chest arrives at police headquarters.

The chest was shipped as freight (properly encased in shrink-wrap) via a bus company and addressed to a local clinic. But one by one, the clinics checked their records and realized they had not ordered any drugs or other vital materials that must be shipped on ice and shrink-wrapped. The chest winds up at the police station by a kind of default mechanism. The cops open it and find four severed human heads.

The newspaper says an investigation has been launched.

At the same time, two laborers on a local ranch stumble into some armed men and are promptly cut down.

I read the World War II memoir of Eric Severeid, a son of Velva, North Dakota. At that time, he was a CBS radio correspondent. Later, he was part of television news and for years read brooding and vague commentaries each evening, a voice sandwiched amid the mayhem of nightly items.

He went off to his war as a young man who believed in a raft of ideas labeled progressive, who believed that people were basically decent and wanted to live in peace in democratic societies.

The war threatened his beliefs.

He found an appetite for murder, and he had trouble with this fact. He saw U.S. soldiers kill prisoners without a qualm. He saw average people, French and Italian, turn into killers once the fragrance of “liberation” floated over their towns and villages.

On the American election day, a man is found against the metal bars of a window, arms spread in the crucifixion style, feet firmly on the ground, his face hidden by a pig mask. Children walk past on their way to school. A few days later, a man is found at dawn dangling from a bridge. His severed head is located wrapped in a black plastic bag at the Juárez monument to newsboys in the Plaza of the Journalist.

Like many such tales in the city, it was written up for the daily paper by Armando Rodriguez, who has this very morning, a week after the severed head was left at the monument to journalists, filed his 907th story of the year, and then he takes ten hits from a 9 mm as he warms up his car, his young daughter beside him, in order to take her to school.

The burned body is dumped at the police station, arms severed at the elbow, each hand holding a grill lighter.

He has been strangled and then burned with cigarette lighters.

He has been shot with an AK-47.

A message left with the carcass denounces the dead man as an arsonist.

At the time the crisp body is found, the local police get death threats over their radios.

The cops take down the blanket on which the accusation against the dead was painted, that he was an arsonist.

Then a message comes over their radios to put it back up, pronto.

They do.

This police district is very productive in producing dead policemen.

Since the killing began warming up last January and the first message was posted of cops to be killed, this area has been rich in dead police.

Back then, the message, placed over a funeral wreath of flowers, contained the names of seventeen agents, identified by surname, code, and sector.

For those who continue not to believe: Z-1 Juan Antonio Román García; oficial Martín Casas, Z-4 del distrito Aldama; Adán Prieto, Z-3 del distrito Babícora; Eduardo Acosta, Z-4 del distrito Chihuahua; oficial Arvizu, Z-6 del distrito Aldama; oficial Rojas, Z-5 del distrito Benito Juárez; oficial Rojas, del distrito Cuauhtémoc; Originales Z-4 del distrito Cuauhtémoc; oficial Balderas, Z-3 del distrito Aldama; oficial Villegas, Z-3 del distrito Delicias; oficial Casimiro Meléndez, del distrito Babícora; Evaristo Rodríguez, oficial del distrito Cuauhtémoc; oficial Silva, Z-5 del distrito Cuauhtémoc; oficial Vargas, del distrito Cuauhtémoc; oficial Guerrero, del distrito Cuauhtémoc; Gerardo Almeralla, agente de Vialidad; y el oficial Galindo, del distrito Aldama.

Since that greeting, many on the list have died. Or quit. Or fled.

This is something new and yet something old. This is what Eric Severeid saw in June 1944 on the day Rome was liberated from the Germans. He was thirty years old and battle hardened by all the reports he’d filed from China and Britain and North Africa and Italy. He’d bailed out of a plane on the Chinese/Burma border into jungle controlled by the Japanese and made it out alive. He’d seen men die. He’d learned there was a chasm between his educated beliefs about the war and the feelings of the soldiers who had to fight and die in the war. So when Rome was liberated, he already knew about killing and evil and violence and things he never really wanted to know, and now knew he could never forget. He left a brief page in his memoir,

Not So Wild a Dream,

published in 1946:

At midnight I wandered toward my hotel and in the moonlight came upon two tired American paratroopers from Frederick’s regiment, who were sitting disconsolately on the curbing. They were lost, had no place to stay. . . . I took them to my room and they stretched out on the floor. We talked a while, and one of them, a brawny St. Louis man who had been a milk-wagon driver, said: “You know, I’ve been reading how the FBI is organizing special squads to take care of us boys when we get home. I got an idea it will be needed, all right. See this pistol? I killed a man this morning, just to get it. Ran into a German officer in a hotel near the edge of town. He surrendered, but he wouldn’t give me his pistol. You know, it kind of scares me. It’s so easy to kill. It solves your problems, and there’s no questions asked. I think I’m getting the habit.”

Esther Chávez Cano died on Christmas morning 2009.

She lived to help heal the wounds of Ciudad Juárez,

she insisted on justice from those in power.

And demanded action from the rest of us.

After That Year

More troops arrive

and more corpses arrive. By the summer of 2009, Juárez looks back on the slaughter of 2008 as the quiet time. This book began because I was astounded by the killings of January 2008—48. This would have spelled out to 576 murders a year, almost double the previous record of 301 in 2007. Now a murder rate of 100 a month would feel like the return of peace to the city. July 2009 is the bloodiest month in the history of the city, with 244 murdered. In August, 316 more go down. There are at least 10,000 troops and federal police in the city, with the murders, 1,440 to date, surpassing the 788 for the same date in 2008—an increase of 83 percent. Small businesses fold all over the city as the extortion rates rise. Forty percent of the city’s restaurants close. The city now has an estimated 150,000 addicts. El Pastor believes that 30 to 40 percent of the population depends on drug money for income.

MONTHLY MURDER TALLIES

FOR CIUDAD JUÁREZ, 2008-2009

| | 2008 | 2009 |

|---|---|---|

| JANUARY | 46 | 154 |

| FEBRUARY | 49 | 240 |

| MARCH | 117 | 73 |

| APRIL | 55 | 85 |

| MAY | 136 | 127 |

| JUNE | 139 | 221 |

| JULY | 146 | 260 |

| AUGUST | 228 | 316 |

| SEPTEMBER | 118 | 310 |

| OCTOBER | 181 | 324 |

| NOVEMBER | 192 | |

| DECEMBER | 200 | |

| TOTAL | 1,607* | |

From various Juárez press sources.

* This total does not include the 45 bodies recovered by federal agents in February and March in clandestine graves in two houses. With these added, the total rises to 1,652.

I am sitting with a Juárez lawyer at a party, and he explains that there has been a failure of analysis. He tells me criminology will not explain what is happening, nor will sociology. He pauses and then says that we must study demonology.

Some blame the violence on a war between cartels, some blame poverty, some blame the army, some blame the army’s fighting the cartels, some blame local street gangs, some blame drugs, some blame slave wages, some blame corrupt government.

But regardless of the blame, no one can figure out who controls the violence, and no one can imagine how the violence can be stopped.

But everyone grows numb. Murders slip off the front page and become part of the ordinary noise of life. By early December, 2,400 have died.

Juárez is rated by some counts to be the most violent city in the world.

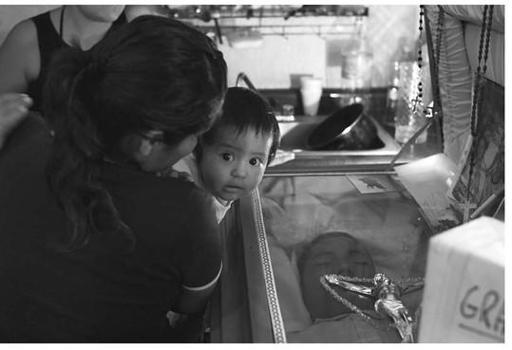

ON AUGUST 13, 2008, EIGHT PEOPLE WERE KILLED BY ARMED COMMANDOS AT CIAD #8, A DRUG REHABILITATION CENTER FOR THE POOR IN COLONIA PRIMERO DE SEPTIEMBRE IN CIUDAD JUÁREZ. THEY WERE HOLDING A PRAYER MEETING. THE BOY IN THE COFFIN, LUIS ÁNGEL GONZÁLEZ, “SIGNO,” 19, A MEMBER OF LOCOS 23 GANG, HAD CHECKED IN FOR TREATMENT FOUR DAYS BEFORE HIS MURDER. THE MEXICAN ARMY REMAINED OUTSIDE THE REHAB CENTER WHILE THE SLAUGHTER WENT ON FOR FIFTEEN MINUTES, WITNESSES SAID.

APPENDIX

THE RIVER OF BLOOD

People with brown skin are next door to invisible.

—GEORGE ORWELL, 1939

At first, it is simply a clerical task. Read the papers and put down the names, if given, and the time and cause of death. Then the volume grows, and the reports get sketchy. People disappear, and their fates never get reported. Nor are there any real numbers on the kidnapped since families hardly ever report such events, because they are afraid of being murdered. Then, the killings per day get larger, the reporters more and more threatened. By June 2008, the city cannot handle its own dead and starts giving corpses wholesale to medical schools or tossing bodies into common graves. The list of the dead becomes a dark burden as solid information dwindles. And so it finally trails off, a path littered with death and small voices whispering against the growing night. But it gives a sense of the rumble of daily life as the bullets fly and the killers roam unimpeded. In January and February 2008, newspapers and voices on the streets all marveled at the horror of more than forty killings in a month—a number never before recorded in Ciudad Juárez. By May 10, the work becomes unbearable, and the tally of that moment records only a fourth of the slaughter the year would bring. Of course, all this happens before things get really bad in the city. By the end of 2008, the monthly totals reached beyond two hundred. By summer 2009, more than three hundred murders in a month became normal in Juárez.