Muslim Fortresses in the Levant: Between Crusaders and Mongols (54 page)

Read Muslim Fortresses in the Levant: Between Crusaders and Mongols Online

Authors: Kate Raphael

Tags: #Arts & Photography, #Architecture, #Buildings, #History, #Middle East, #Egypt, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Social Sciences, #Human Geography, #Building Types & Styles, #World, #Medieval, #Humanities

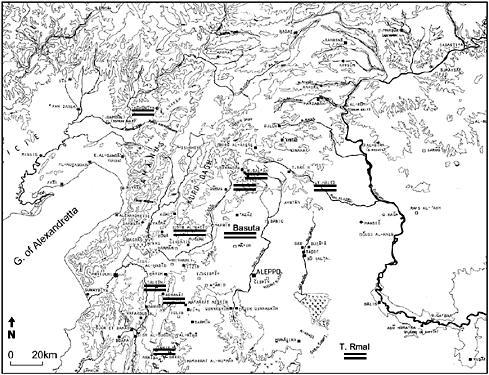

Map 3.2

Fortresses in the vicinity of Aleppo taken by Baybars, according to Ibn Shaddād, but never rebuilt.

, Tall-Khālid and Ārmanāz (

, Tall-Khālid and Ārmanāz (

Map 3.2

). Only half of these fortresses have been identified. The closest to Aleppo are 40–50 km away, while the most distant are approximately 80 km from the city. At the end of the paragraph Ibn Shaddād adds that there are many more fortresses apart from those he has mentions in his list.

36

The balance between the garrisons and the Mamluk field army as well as the dependence of each on one other should be taken into account when one tries to follow the decisions made by Baybars as to which fortresses should be left in ruins and abandoned and which fortresses should be held and rebuilt.

Al-Bīra and were chosen by Baybars to guard the Euphrates frontier. It seems that preference was given to sites whose maintenance did not require an enormous outlay and thus they did not become a burden on the local population or the sultan’s treasury. A further two fortresses were added to the defense of the Euphrates frontier in later years, when the Mamluk army had grown considerably in size and the geopolitical situation had changed.

were chosen by Baybars to guard the Euphrates frontier. It seems that preference was given to sites whose maintenance did not require an enormous outlay and thus they did not become a burden on the local population or the sultan’s treasury. A further two fortresses were added to the defense of the Euphrates frontier in later years, when the Mamluk army had grown considerably in size and the geopolitical situation had changed. was taken and rebuilt after Acre had fallen in 1291; it was of outstanding size and probably had a garrison similar in numbers to that at Safad, approximately 1,700 men.

was taken and rebuilt after Acre had fallen in 1291; it was of outstanding size and probably had a garrison similar in numbers to that at Safad, approximately 1,700 men. was rebuilt by

was rebuilt by in 1333–4, a decade after the peace treaty was signed between the Īlkhānids and the Mamluks. It is difficult to explain the immediate threat that brought about the establishment of these fortresses. This large-scale

in 1333–4, a decade after the peace treaty was signed between the Īlkhānids and the Mamluks. It is difficult to explain the immediate threat that brought about the establishment of these fortresses. This large-scale

military construction program was implemented during times of peace, when the Mongols were occupied elsewhere and the Mamluks were not busy on other fronts.

37

Although most Mamluk fortification work started almost immediately after a fortress was conquered it sometimes took several years for projects to be completed.

Most fortresses could not endure a siege of more than a few weeks. In 1259 al-Bīra was conquered within two weeks by a section of the Mongol army headed by Hülegü. In the winter of 1312–13 the garrison at managed to withstand siege for a whole month.

managed to withstand siege for a whole month.

38

The Mamluk army played a key role in the support of the Euphrates fortresses, for resisting an Īlkhānid siege force could only be done by a full-size and well-trained field army. On a number of occasions the Īlkhānid army left the scene before or while the Mamluk forces were making their way north. Without the support of the Mamluk field army the strength and existence of the frontier strongholds was questionable. An interesting point to note is the fact that reinforcements were seldom sent from any of the neighboring strongholds. They always arrived from the central Syrian cities and/or directly from Cairo. It seems the number of men per garrison was carefully calculated and that even in times of emergency the garrisons could not afford to send reinforcements to a neighboring site.

The decisions made y Baybars may seem at times to be random. Although it is possible to rationalize most of his moves, one should keep in mind that unlike many of the Frankish, Ayyubid, Armenian and strongholds that were built on virgin soil, Baybars avoided building new fortresses. It seems that to some extent his decisions were influenced by the distribution of existing fortifications. This policy was partly impelled by a feeling of urgency, and possibly by the need to reduce outlay. The field army enjoyed a higher priority, and a large percentage of the sultan’s funds were invested in buying Mamluks and arming his forces. Above all, it was difficult to justify the building of new fortresses in view of the fact that the region already had numerous strongholds of every type and size.

strongholds that were built on virgin soil, Baybars avoided building new fortresses. It seems that to some extent his decisions were influenced by the distribution of existing fortifications. This policy was partly impelled by a feeling of urgency, and possibly by the need to reduce outlay. The field army enjoyed a higher priority, and a large percentage of the sultan’s funds were invested in buying Mamluks and arming his forces. Above all, it was difficult to justify the building of new fortresses in view of the fact that the region already had numerous strongholds of every type and size.

There are three extant lists that summarize the conquests of Baybars. The first is that of Ibn , who served as Baybar’s private secretary (

, who served as Baybar’s private secretary (

kātib al-sirr

). His short account lists the fortresses in Syria and Trans-Jordan that were destroyed by the Mongols during their first invasion. Once Baybars became sultan he immediately saw to the reconstruction of all the ruined strongholds; moats were cleaned and fortresses strengthened or enlarged. Soldiers, funds and military supplies were sent to each site. The list includes Damascus, , Shayzar and Shumaymish.

, Shayzar and Shumaymish.

39

Many other sites rebuilt by Baybars are not mentioned and it seems that the list follows the main route of destruction left by the Mongols. Although none of the sites listed were close to the Frankish or the Mongol frontier, they were all rebuilt in the sultan’s reign on the supposition that if the Īlkhānids invaded they would take a similar route.