Muslim Fortresses in the Levant: Between Crusaders and Mongols (75 page)

Read Muslim Fortresses in the Levant: Between Crusaders and Mongols Online

Authors: Kate Raphael

Tags: #Arts & Photography, #Architecture, #Buildings, #History, #Middle East, #Egypt, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Social Sciences, #Human Geography, #Building Types & Styles, #World, #Medieval, #Humanities

Because the Mamluks mainly added to and built upon existing fortresses their work has been consistently overlooked or else documented as a phase within Crusader, Ayyubid or Armenian fortresses. It has rarely been studied as an independent subject.

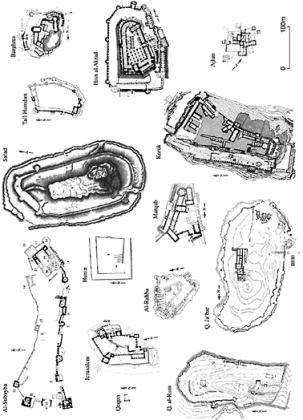

Eight fortresses are discussed in this chapter (

Map 3.4

;

Figure 4.1

).

6

Starting from the Mamluk inland fortifications, is of particular importance, since the Mamluk construction is a direct continuation of the Ayyubid work. It is the only rural fortress in this study that was built by the Ayyubid rulers and was further restored and enlarged by the Mamluks, with no Frankish intervention.

is of particular importance, since the Mamluk construction is a direct continuation of the Ayyubid work. It is the only rural fortress in this study that was built by the Ayyubid rulers and was further restored and enlarged by the Mamluks, with no Frankish intervention.

Figure 4.1

Mamluk fortresses from the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries drawn on the same scale

Safad, located in the Upper Galilee has only been partly excavated, and a considerable amount of work is still required in order to fully understand the scale of restorations conducted by the Mamluks. The historical sources, on the other hand, are remarkable and give a detailed account that few sites offer. Qāqūn is one of the few examples of the smaller fortresses restored by the Mamluks; it is also the only Frankish stronghold on the Sharon plain that was not destroyed by Baybars. The Mamluk fortifications in Trans-Jordan are represented by Karak, parts of which are securely dated by inscriptions. The fortress was extensively built and almost doubled its size in the early years of Baybars’s reign. and al-Bīra represent the border fortifications which secured the Euphrates fords. From the Euphrates I move west into Cilicia, choosing Baghrās and

and al-Bīra represent the border fortifications which secured the Euphrates fords. From the Euphrates I move west into Cilicia, choosing Baghrās and , which guarded the passes over the Amanus mountain range.

, which guarded the passes over the Amanus mountain range.

As well as endeavoring to represent different geographical regions within the Mamluk sultanate, the eight fortresses are all well dated, either by historical sources or inscriptions found in situ and sometimes by both.

The language of construction work, time schedules and officials

The historical sources

Very few periods in history were as fortunate as that of Julius Caesar and Augustus in having an architect and military engineer who wrote about the buildings of his time. Vitruvius,

7

in his ten volumes

On Architecture

(written in the second half of the first century BC), gives a detailed survey of methods of construction, the various materials available, problems concerning constructions and other valuable information. His books cover public, military and private buildings. No matching Mamluk source has yet surfaced. Although the Mamluk historical sources are numerous and rich, none deal explicitly with architecture. Several of the contemporary chroniclers were highly respected scholars, but they all appear to have lacked the knowledge and understanding of architecture and construction required in order to give a clear and detailed description of the buildings standing before them.

8

Strongholds and city fortifications in the Mamluk sultanate are frequently listed in contemporary works, but the descriptions are often poor and brief, usually coming after a relatively long account of the siege in which the fortress was taken. In some cases sweeping summary accounts are given concerning a large number of strongholds and the restoration works carried out by the sultans. Ibn list of ten fortresses and citadels provides only very general information: “their moats were cleaned and their curtain walls widened.”

list of ten fortresses and citadels provides only very general information: “their moats were cleaned and their curtain walls widened.”

9

No further details are given regarding the buildings, and one is left with a slight suspicion that the account may be somewhat unreliable. This feeling is strengthened when Ibn information is examined in the light of the archaeological remains, as at least one of the fortresses in this report did not have a moat and three of the sites did not have their curtain walls rebuilt or widened.

information is examined in the light of the archaeological remains, as at least one of the fortresses in this report did not have a moat and three of the sites did not have their curtain walls rebuilt or widened.

10

In describing the organization of Karak by Baybars, Ibn states that the fortress was carefully inspected from the outside and the inside and that the Sultan ordered

states that the fortress was carefully inspected from the outside and the inside and that the Sultan ordered

the reconstruction of what was necessary.

11

But that is as far as the report goes; no further details are given as to what was damaged or which weak sections needed to be strengthened.

The siege and reconstruction of Safad is mentioned by several chroniclers, it will be used here to show the main problems arising from the different sources.

Ibn (d. 692/1292) writing reeks of court politics. His excessive admiration for Baybars, arising from his appointment as

(d. 692/1292) writing reeks of court politics. His excessive admiration for Baybars, arising from his appointment as

kātib al-sirr

and his position as official biographer of the sultan, often surfaces. Much of his account of the reconstruction of Safad concerns the Sultan’s fine leadership.

12

It appears that Ibn received his information from someone who participated at the siege and was present in the reconstruction. Ibn al-Furāt (d. 807/1405) relies heavily on Ibn

received his information from someone who participated at the siege and was present in the reconstruction. Ibn al-Furāt (d. 807/1405) relies heavily on Ibn and adds little to our knowledge of fortress construction. Fortifications were obviously of no interest to him or he simply did not see it as his task to report on the subject. His account concerning the reconstruction of Safad is poor in comparison to the detailed description of Baybars’ siege and the new Mamluk garrison that was placed in the fortress. The only buildings he describes are the two mosques that were erected by the sultan, one in the fortress itself and the other in the suburb

and adds little to our knowledge of fortress construction. Fortifications were obviously of no interest to him or he simply did not see it as his task to report on the subject. His account concerning the reconstruction of Safad is poor in comparison to the detailed description of Baybars’ siege and the new Mamluk garrison that was placed in the fortress. The only buildings he describes are the two mosques that were erected by the sultan, one in the fortress itself and the other in the suburb .

.

13