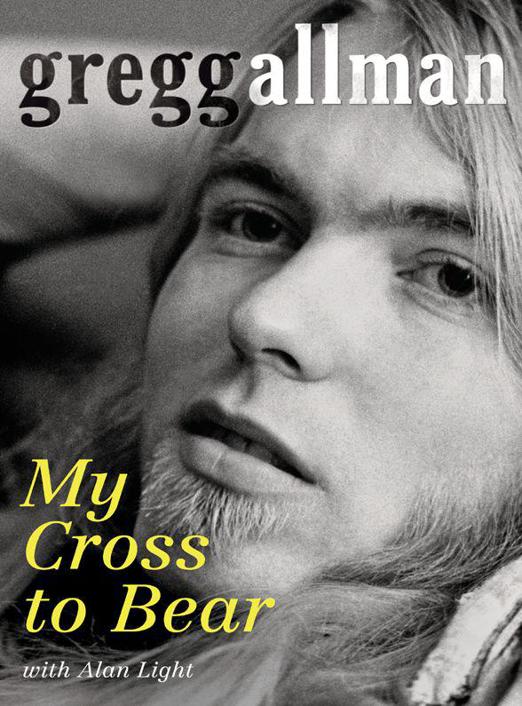

My Cross to Bear

Authors: Gregg Allman

Tags: #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Personal Memoirs, #Music, #Rock, #Biography & Autobiography, #Genres & Styles, #Composers & Musicians

TO BEAR

Gregg Allman

WITH

A

LAN

L

IGHT

To my mom and Duane

Allman Family Archives

My sincere appreciation goes to contributing author John Lynskey, whose insight, knowledge, and experience with the Allman Brothers Band and my career helped to bring this project together. Thanks, bro

.

—G.A.

SEPTEMBER 2011

I was sitting up talking, and I just kind of nodded off. But I didn’t nod off; I was Code Blue. I was bleeding inside, and I was drowning in my own blood

.

What I remember is that I went to sleep and I had the most incredible dream. It was almost like a still life, and the air smelled so good and music was playing. I always have music in my dreams, and whatever type of music it is, it sets the whole mood for whatever’s happening. If it’s a nightmare, it’s some nasty music. But this music was beautiful

.

I was standing at a bridge and it was twilight, and somebody was on the other side. They weren’t motioning, they were just looking at me, but the message got through: don’t come across this bridge. It was all so beautiful, I wanted to go over there and see who it was. All I could see was a silhouette of the person, with hair down to their shoulders. It appeared to be my brother. Maybe it was just somebody standing in my room, I don’t know. But somebody was there, telling me not to come across that bridge. It’s not my time yet

.

January 1995

I

T SHOULD HAVE BEEN THE GREATEST WEEK OF MY LIFE, BUT INSTEAD

I hit an all-time low. The Allman Brothers Band, the band my brother started, the band with our name on it, was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and I flat-out missed it. I was physically there, but otherwise I was out of it—mentally, emotionally, and spiritually. You might say that I had the experience but missed the meaning. Why? The answer is plain and simple—alcohol. I was drunk, man, just shitfaced drunk, the entire time.

I arrived in New York on a Sunday, got drunk, and stayed drunk for five days, including the induction ceremony itself. My memory is a bit hazy, thanks to the booze, but I remember little bits, flashes of this and that, of the week that ultimately changed my life. On that Monday we taped a segment for the

Late Show with David Letterman

, and when I look at a tape of that night, I don’t even recognize the guy singing “Midnight Rider.” My face was puffy and bloated from the booze, and my skin had taken on this gray, sickly pallor, which was accented by the fact that I had shaved my beard. With sunglasses and a top hat to round things out, I was really looking rough.

My voice was suffering as well, but I managed to get through the taping. I spent a lot of time making it up and down the stairs that went from the studio to the green room, where there was a bar. After

Letterman

it was back to the bar at the Waldorf-Astoria for vodka and cranberry the rest of the night.

On Tuesday I had to go get fitted for my tux, and after the fitting we had lunch at a Chinese restaurant. My team had the idea to hold an intervention. They were there to tell me that I needed to go into treatment, and I needed to do it now. There was a plan in place, and treatment had been arranged for me at a center in eastern Pennsylvania. They all stressed how badly I needed to do this, because they told me I was dying, and they couldn’t sit by and watch me slowly kill myself any longer.

It was a speech I’d heard before, but this was different. A little voice told me that enough was enough, and this time I listened. I gave in and told them I would go. I resigned myself to going at the end of the week, but until then I just kept right on drinking, man—I drank constantly. I couldn’t

not

drink, you know? Sad but true: I could not not drink.

Later in the day, we headed over to Sony Studios on West 54th to do some vocal overdubs for the Allman Brothers record

Second Set

. Tommy Dowd, our beloved producer, was there, and what should have been real simple became an ordeal. I couldn’t get the fucking words to come out right. The alcohol had tied my tongue in knots, and the guys in the booth were literally cutting one word at a time. I was spitting and sputtering; we finally got it done, but it was torturous.

We had another TV appearance scheduled for Wednesday, this time on

Late Night with Conan O’Brien

. We did

Conan

during the day, and played a couple of songs, including an extended version of “Statesboro Blues” that just went on and on. Dickey Betts and Warren Haynes really were unbelievable, but I was just trying to hold on. I was a scary-looking sight—my eyes were hollow, empty, and so yellow that they looked like a couple of lemon slices.

After that, we were scheduled to rehearse for the induction ceremony over at the Waldorf, where the band was going to work up a shorter version of “One Way Out.” I just couldn’t make it. Sorry, but I was worn out, and I couldn’t do it.

Thursday was the ceremony, in the ballroom of the Waldorf. That morning, I took some shot glasses, and I measured them out just right. I didn’t wanna get drunk. So I lined up the glasses, took the shots, and I was doing all right. Back then, I didn’t have the shakes—I had the hydraulic jerks. I had to keep a half-pint up under the bed in case I sobered up in my sleep. I could hardly walk, I was shaking so bad.

One of my old buddies called me from downstairs, and I went down and saw everybody I ain’t seen for a hundred years. Next thing you know, I was at the lobby bar. “C’mon, man, let me buy you a drink.” They started collecting in front of me, from people all around the bar. Needless to say, I sat there and got shitfaced. Believe it or not, this turned out to be a good thing.

My dear mother, Geraldine, was there, and she was very worried about me, as were a lot of people by this point. I found out later that Jaimoe, my bandmate and a sweet man, was upstairs in his room, and he was actually crying because he thought I was dying—literally dying.

I managed to introduce my mother to Ahmet Ertegun, the founder of Atlantic Records and someone who had meant so much to my brother and me. I was trying to pace myself, but when it was time for me to go onstage, I was in bad shape. Willie Nelson presented the band with our award, and when I got up there he asked me, “You all right, Gregory?”

“Willie, I am

not

all right,” I replied. I tried every trick I knew to keep people from knowing I was drunk, but I couldn’t stand up straight; I was kind of weaving.

One thing I’d been concerned about beforehand was my acceptance speech. I had to say something, so I wrote several ideas down on this little notepad—little phrases and what have you, things I had said in the past. I’d organized them onto one sheet of paper, and that became the speech I was going to give. There were a lot of things I wanted to say—about my mother, about the fans, about Bill Graham—but instead I just got up there and said, “This is for my brother. He was always the first to face the fire. Thank you.” That’s about all I could get out, and it was one of the most embarrassing moments of my life. I had to get the hell off that stage, because I was getting a little woozy.

After the band performed “One Way Out,” I got out of there as fast as I could. I went up to my room, changed into my jeans and leather jacket, and headed back to the bar, still clutching my Hall of Fame award. People were surrounding my table, telling me how great I was, buying me drinks, but I felt nothing. I had just won the highest award there is in my profession, and I didn’t give a damn—I just wanted another drink. People would ask to hold my award, and I’d let ’em; somebody probably could have run off with it, you know?

The agreement that I had made was that the next morning, a Lincoln Town Car would take me to a treatment center, which was actually a farm in east-central Pennsylvania. It was about a four-hour ride, and we left around noon. I emptied the minibar in my hotel room for the drive, and I had some Valium as well. I had all these little airplane bottles of booze in my coat pocket, and we got in the car and started driving. I spent the ride taking pills and washing them down with those mini-bottles. Somewhere in Pennsylvania, we stopped at a little Italian restaurant to get something to eat, but of course my meal ended up being four double vodka and cranberry—I never touched my veal marsala.

We got back in the car, and we finally arrived at the center, which is in a little town by a river. I had two mini-bottles of vodka left in my jacket, so I put them in my fist, took the lids off of both of them, upended them like a double-barreled shotgun, and emptied them both as we pulled into the driveway. It was so pathetic, but I remember thinking, “You are better than this, and it’s time for this crap to stop.” I knew it was time for a change.

Welcome to the story of my life.

A day at the beach with my brother

Courtesy Brenda Allman, Allman Family Archives