My Name Is Mina (14 page)

Authors: David Almond

“John O’ Groats.”

“County Kerry.”

“Ayers Rock.”

“Lhasa.”

Later, when I go to bed, I pin some words above my bed and hope to dream.

At the start, it wasn’t really like a dream at all. It was quite like waking up. Mina found herself in her own bedroom, and it was exactly like her own bedroom. Then she realized that there were two Minas. One lay fast asleep in bed, and one was standing at the bedside looking down at the Mina who lay fast asleep in bed.

That’s strange, she thought. I’m looking at myself. How can that be?

As she thought this thought, she started to rise towards the ceiling. The Mina in bed did not stir. Mina-who-was-rising saw that there was a kind of shining silver cord that stretched between herself and Mina-on-the-bed. The cord joined the two Minas together, even though they were apart. The Mina who was rising wondered if she should feel scared about what was happening, but really there seemed to be nothing scary about it at all. She looked down at herself, at the pale sleeping face, the closed sleeping eyes, the pitch-black hair. She saw the duvet rising and falling gently as Mina breathed. It all

seemed so calm and so comfortable. She smiled, and rose even higher, through the ceiling, into the dark attic space above. She saw the boxes of her old toys that were stacked up there, boxes of her mum’s papers, boxes of Christmas decorations and old books. The shining silver cord stretched through the attic floor towards the now-hidden Mina-on-the-bed. And she kept on rising, through the roof itself, and now she was above the house, in the night, with the moon and stars above, and the house and Falconer Road below, and with the silver cord stretching through the roof slates towards Mina-on-the-bed. She gasped, and for a moment the cord seemed to tighten, as if it was about to pull her right back to where she’d come from, but she whispered to herself, “Don’t be scared, Mina. Don’t stop it now.”

And she and the cord relaxed and she rose high above the house, and the street, and she saw the strings of streetlights, and the darkness of the park, and the whole city, and the glimmering river running through it, and the spiral of the motorway, and the roads that ran out toward the moors, and she saw the huge dark sea with the reflections of the

moon and stars on it, and a spinning lighthouse light, and the lights of a lonely ship far out upon the seas.

And she laughed.

“I’m traveling!” she said. “I shall go to … Seaton Sluice!”

And as she said the name of the little seaside town she descended again and found herself hovering above the town she’d been to several times in her waking life. There they all were, the long beach and the turning waves, the white pub on the headland, little tethered fishing boats, the narrow river running into the sea.

The silver cord vibrated and shimmered. It stretched away from her towards where she’d come from, linking Mina-at-Seaton-Sluice to Mina-on-the-bed.

She hovered. She wondered.

“Cairo!” she whispered.

And she rose again, and off she went towards the east, across the North Sea, across the whole of Europe with its great cities and its snow-capped mountains, and she looked down and thought to herself, That must be Amsterdam! The Alps! Milan!

Belgrade! Athens!! And she traveled across the Mediterranean Sea towards the northern shores of Africa, where the sky was beginning to lighten with the dawn.

She saw the great great dusty city of Cairo and heard its din and roar, and saw the pyramids beyond its edge, rising over the desert. She traveled closer. She hovered over the tip of the greatest pyramid. She eased herself gently downward until she stood there, right on the point of the Great Pyramid of Giza, with the other pyramids and the great sphinx and the desert on one horizon and the city of Cairo on the other. And she shivered with the joy of it.

And the silver cord that linked Mina-on-the-pyramid to Mina-on-the-bed suddenly tightened and away she went again, back into the west where it was still true night.

She traveled back over Europe, even more swiftly than she’d come. She paused, high high up, above the clouds that lay like scattered thin veils between herself and the earth. The cities of Europe were like distant star-clusters, like galaxies.

And she streaked down towards Rome. She saw the streetlights, the headlights of a few cars moving through the streets, and with a gasp of delight she saw the floodlit Colosseum and St. Peter’s Square and the Trevi Fountain, places she knew only from books until now. Then the cord tugged her harder, faster, and she flew again. The land below was just a blur.

Just one more place! she thought. Durham!

And she saw the cathedral and the castle, the river snaking around them, and to the east the dawn kept rising, rising, as if it was pursuing her. And she sighed and said, “OK! Back home to bed!” And suddenly she was above the park, and the silver cord vibrated and shimmered as it drew her home.

She woke as the early light shone through the window and birds chorused outside.

“Peru,” she murmured. “Alice Springs. Vladivostok. I’ll go to all those places, too.”

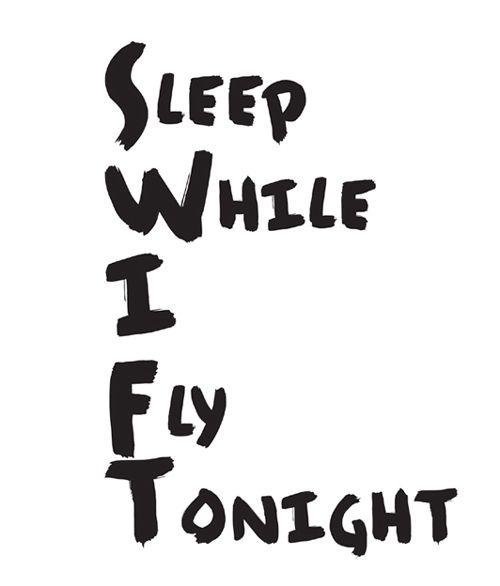

EXTRAORDINARY ACTIVITY

Go to sleep.

Sleep while you fly.

Fly while you sleep.

The days are passing quickly. Maybe it will soon be properly spring at last. The family have bought the house. The mum and dad come with stepladders and buckets and mops and brushes. They clean and scrub for hours at a time. Each day I climb high in the tree. Each day the blackbirds squawk, Get back, girl! Squawk! You’re danger! Squawk!

Now I’m sitting at the table by my window in my room. And it’s time to tell the tale of the Corinthian Avenue Pupil Referral Unit.

When Mum said she wanted to take me out of school and educate me herself, a man and a woman from the council came to the house. I don’t remember their names. Ms. Palaver and Mr. Trench, perhaps. They sat together on the sofa and drank tea and nibbled biscuits and tried to look caring and oh-so-concerned. Ms. Palaver (who, I noticed, kept well clear of the fig rolls) watched me out of the corner of her eye. I sat very prim and very proper on a piano stool. They said that legally, Mum was of course well within her rights to make this decision. Did we understand the implications, though? Educating me at home would be quite a drain on

Mum’s energy and time. We would not have the facilities of school. I would not have the benefit of company of children of my own age. Mum said we realized those things. We were quite prepared for them. She said we were quite happy about them. And our plan for home education might not last forever.

“Though it might,” I said quickly.

Ms. Palaver looked at me in surprise. I looked back at her. She was wearing a black suit with a white blouse and silver earrings. Mr. Trench was also in black and white. I was about to ask them if they were off to a funeral but I thought perhaps not. So instead, somewhat to my own surprise, I said,

“Ms. Palaver.”

“Yes, dear?”

Mum gave me a look.

“I’m not certain I understand,” said Ms. Palaver.

“Never mind,” I said.

I sat up straight again. I looked past Ms. Palaver into the street.

Mum started talking about how Mina had an adventurous mind. She said she’d be able to commit lots of time to Mina. She talked about Mina’s dad and about Mina being an only child and about how she had no objections to St. Bede’s itself, but …

“And as for facilities,” I said, “we have a very nice tree in the front garden in which I have many thoughts. And the kitchen is a fine laboratory and art room. And who could devise a better classroom than the world itself?”

Mum smiled.

“As you see,” she said, “Mina is a girl with her own opinions and attitudes.”

Ms. Palaver peered at me closely. I could see her thinking that Mina was an impertinent girl with her own pompous crackpot notions.

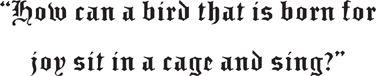

“To be quite frank,” I said, looking straight back at her, “We feel that schools are cages.”

“Indeed?” said Ms. Palaver.

“Yes,” I continued. “We feel that schools inhibit the natural intelligence, curiosity and creativity of children.”

Mr. Trench rolled his eyes.

Mum smiled and shook her head.

Ms. Palaver said again, “Indeed?”

“Indeed,” I said.

“Before you make your final decision, Mrs. McKee,” said Mr. Trench, “you might find it worthwhile to have Mina spend a day at Corinthian Avenue.”

“Corinthian Avenue?” said Mum.

“It’s where we send children who don’t …”

“Or who won’t …,” said Ms. Palaver.

Mr. Trench brought out a leaflet from the inside pocket of his black jacket. He held it out to Mum.

“Can’t do any harm,” he said.

EXTRAORDINARY ACTIVITY

Read the Poems of William Blake

.

(Especially if you are Ms. Palaver.)

The thought of Corinthian Avenue makes me edgy, so I pick up my book and my pen and head downstairs. This is something that needs to be written in the tree! Mum’s on the phone in the living room. I get an apple from the fruit bowl and bite into it. I put some trainers on. It looks chilly outside so I put a jacket and scarf on. She’s still on the phone.

“I’m going outside!” I call.

She doesn’t answer.

“I’m going out, Mum!” I call again.

I listen. I shrug and head for the door.

Then she’s there, coming out of the living room.

I point to the book and pen.

“Going into the tree,” I say.

“OK.”

“Who was that?”