My Name is Number 4 (2 page)

Read My Name is Number 4 Online

Authors: Ting-Xing Ye

(Left) My paternal grandfather, Ye You-quan, who was severely beaten by Red Guards because he once owned land and a business

.

(Right) My great-aunt, Chen Feng-mei, given to my family as a housemaid by her mother after two arranged marriages didn’t work out

.

A week after my birth, Mother brought me home from the Red House Hospital, so named because red paint covered its brick walls, wooden window-frames and doors, to my family’s three-room apartment in the centre of the city. Shaded by plane trees, Wuding (Valiant Tranquillity) Road ran east and west through the former International Settlement and many

long-tang

—lanes, some as wide as two cars side by side, some only shoulder width—connected with it, forming a densely populated yet quiet neighbourhood. Shanghai itself, only ten miles wide and ten miles long, was inhabited by about six million people. We lived in Zi Yang Li—Purple Sunshine Lane.

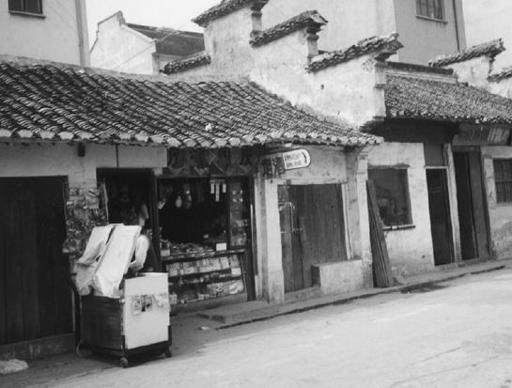

The main street of the town of Qingyang, where my father was born and raised

.

Our two-story brick building was a traditional Shanghai-style house, built in a square U-shape around a courtyard or “sky-well” that served as the front entrance. Two black-lacquer doors, heavy and tall, with brass door-knockers shaped like dragon heads with rings through their noses, guarded the courtyard. Residents used the back door, however, reserving the front for occasions such as weddings and funerals.

In all, eight families lived in six apartments, three at each level. Two water taps in the tiny corridor at the back served all the families, and their use was strictly regulated and policed by our neighbour, Granny Ningbo. The upper tap, with its brick sink, could be used only to wash food, clothing and dishes. The lower one was for cleaning chamber pots and rinsing mops. On each floor, one small kitchen served four families. From the roof terrace I could see the chimney of the Zheng Tai Rubber Shoe Factory, which my father owned.

Where Purple Sunshine Lane intersected with Wuding Road was the

cai chang

—food market. Its rough plank stalls stretched about thirty yards along both sides of the shady street. The centre of our neighbourhood, it opened at six o’clock in the morning, but lineups for popular food like pork bones and fat, which were cheaper and required fewer ration coupons, began to form hours earlier. Some residents would get out of bed early, take up spots near the front of the line, then sell them for a few cents. By early afternoon the market was closed, and the residents used the empty stalls to make quilts on or to air their bedding.

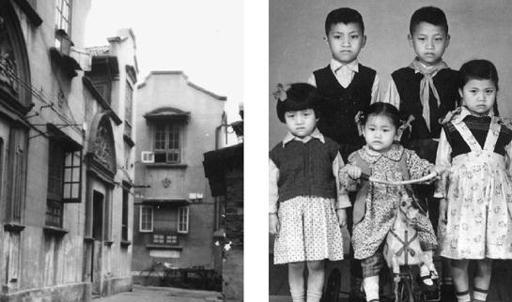

(Left) The “stone arched” house in Purple Sunshine Lane, downtown Shanghai, where I was born and raised

.

(Right) My four siblings and I in 1956. Back row, left to right: second eldest brother, Number 2; eldest brother, Number 1. Front row, left to right: me; younger sister, Number 5; elder sister, Number 3

.

(Left) Number 3 and I, autumn 1957

.

(Right) Purple Sunshine Lane, showing laundry drying on bamboo poles overhead

.

For several years the sky-well, the lane and the busy market were my world.

One day when I was four years old, my father came home from the factory with a big red silk flower pinned to the lapel of his Western-style jacket. Even at that age I knew that wearing a red flower, real or not, meant praise and honour. But Father didn’t look happy about his prize. He limped past me, tossing the flower on the dinner table, and closed the bedroom door behind him. I stared longingly at the red blossom. From inside the bedroom, I heard Father and Mother talking. Only then did I realize that Father had come home early. All my older siblings were still in school and two-year-old Number 5 was having a nap.

Mother came out of the room and saw me eyeing the flower. She said I could have it so long as I kept quiet. She helped me pin it to my jacket and I rushed joyfully downstairs to the sky-well, sporting my colourful reward. I didn’t know that Father had been given the flower for surrendering his factory—the enterprise his grandfather had established and he had operated for almost twenty years—to the government. In return, he was to receive a ridiculously meagre compensation of cash and bonds, paid in installments over seven years.

2

Father was kept on as “private representative” to run the factory he used to own. But when he insisted on claiming his compensation, he was labelled a “hard-minded capitalist” who, the government said, could be reformed only through hard physical labour. Thus, before I turned five, my father had fallen from a respected and prosperous business owner to a labourer.

Even though I was too young to understand the momentous changes that worried Mother, Father and Great-Aunt, I was old enough to notice certain changes. Father no longer wore his Western-style jacket and tie. Instead he put on a dark blue or black worker’s jacket buttoned up to the neck. Despite his physical disability—a childhood attack of meningitis had crippled him in one leg and he had to walk with a cane—he was assigned to one of the most menial jobs in the factory, pushing a heavy wooden cart loaded with rubber shoe uppers between workshops. It was the humiliation and deep wound to his pride that led him to make a decision that turned to tragedy.

One morning in April 1959, Father left home to go to work as usual. It was the last time I saw him walk. Later that day, Mother was called to a district hospital, where she learned that without telling anyone in the family Father had undergone surgery to cure his limp. The operation had been botched and Father was paralyzed from the waist down. Mother was horrified to see Father’s entire torso wrapped in bandages that hid a wide scar from the base of his neck to his pelvis. After three years of suffering, confined to his bed, he passed away at the age of forty-one. I was nine.

Left with five kids and no job, my mother took me time after time on her visits to the factory, where she begged the officials to cash some of the bonds Father had been given when the factory was expropriated. The family had no income

now, she argued, and her children were hungry. Her pleas and my tears had no effect. The bonds could not be redeemed for many years, Mother was reminded.

In order to feed her family, Mother had to face the fact that one of my brothers, seventeen and fifteen at the time, would have to quit school and find a job. One day in May 1963, a year after Father’s death, Mother once again took me with her to the factory. She asked the director to take one of her sons on as an apprentice to help ease her burden and support the family. If there was any way she could have avoided coming to him for help, she said, weeping harder, she wouldn’t be sitting there begging him. An hour later, we were sent away without an answer.

For weeks the atmosphere at home was so tense that I could almost touch it with my fingertips: tense because my brothers were forced to make a decision neither of them wanted; tense because the factory director might turn down Mother’s pleas. Finally the answer came: the Rubber Industry Department would take Number 1 on, not in Father’s factory, but in one that specialized in melting and refining raw rubber.

Mother was relieved but worried. She had wanted her son to work in Father’s former factory because it was nearby. Most of the workers there knew our family and she hoped that they would look after her son. An added complication was that, although the director had specified a position for my eldest brother, Number 1 and Number 2 had decided differently. None of us knew how they had come to the conclusion that Number 2 was to be the one to quit school so

that Number 1, who was one year short of qualifying to sit for university exams, could continue his education. My father had always wanted both of his sons to go to university. Since no one in the new factory knew my family, Number 2 pretended to be Number 1, and by the time the director found out, Number 2 had turned sixteen and was already a skillful worker.

So by the time I was twelve, my family had been on welfare for years. Where I had once sported a silk coat covered with a cotton smock, I now wore my brother’s hand-me-downs. And when I passed up and down our lane, the residents, in particular the members of the neighbourhood committee,

3

suspicious that my “capitalist” mother had secret income, would stop me and lift up my jacket to make sure I wasn’t wearing good clothing hidden underneath. When I became nearsighted, Mother ignored my pleas for prescription glasses because she couldn’t afford to buy me a pair. Instead she gave me a pair Number 2 had outgrown. They caused me constant headaches, and I put them on only when necessary.