My Name is Number 4 (3 page)

Read My Name is Number 4 Online

Authors: Ting-Xing Ye

However, my personality had grown far from the modest and passive Chinese female praised by tradition. In defending myself and my family’s name and, at times, fighting against my bullying neighbours over my mother, I became combative and argumentative. This often saddened Mother. The degradation of poverty and social discrimination had left deep scars.

Our household, meanwhile, struggled to return to normal. In August 1964, I was accepted by an all-girl middle school named Ai Guo—Love Your Country—which had been run by foreign missionaries before the communist government came to power.

4

My sister, Number 3, was enrolled in a new middle school closer to home. Number 1, after scoring extremely high on his entrance exams, won a place at the coveted Jiao Tong University in Shanghai. In five years, he would be an automotive engineer. Mother was especially happy to see Number 2 spending more time at Father’s desk. He had been admitted to a workers’ night school and was taking courses to complete his senior middle school education.

But throughout the fall of 1964, Mother continuously lost weight. She insisted that everything was fine but I frequently saw her holding a hot-water bottle to her stomach. Then one day, her pain drove her to the hospital. The diagnosis was final and devastating: cancer. Two-thirds of Mother’s stomach was removed. We should hope for the best, the doctor said to the five of us.

Six months later, the cancer returned. This time Mother was sent home from the hospital with a gloomy prognosis and a large dose of painkillers. On December 31, 1965, after enduring months of awful pain and misery, Mother too died, three years after Father had left us.

In the days after Mother’s funeral, I refused to go to school. In fact, I felt I wouldn’t mind if I never saw my classroom again. The sight of my parents’ silent bedroom and empty bed frightened me. I was scared to stay home yet scared to go out.

The spring passed slowly as the five of us tried to face our parentless life. In March, Great-Aunt turned 55 and was retired from the factory. She was home all day. Yet her care and devotion to us made me miss my mother more than ever.

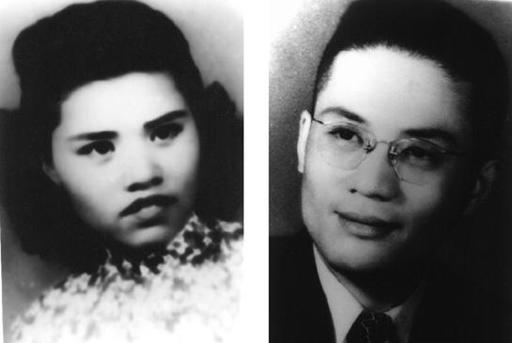

(Left) My mother, Li Xiu-feng, Shanghai, 1948, just before Mao Ze-dong proclaimed the founding of the People’s Republic of China

.

(Right) My father, Ye Rong-ting, Shanghai, 1948

.

One warm April morning, two months before my fourteenth birthday, I was busily working at my desk during a break between classes. Most of us at Ai Guo Middle School used the recess time to make a start on our homework so we would have less to do after school. As I got out of my seat to head for the bathroom I felt something warm and sticky running down the inside of my leg. One of the girls sitting behind me cried out, pointing to the floor, “Look! Blood!” The other girls craned their necks and whispered. There were red spots on the floor and a pool of blood on my seat.

Remembering Great-Aunt’s gruesome tale of her cousin bleeding to death from a gastric ulcer, I was suddenly sick with terror. I have to get home, I thought frantically, snatching up my belongings and stuffing them into my bag. I adjusted the strap so the bag would cover my bottom and raced out of the school.

I ran all the way. First Father, then Mother. Now it was my turn to die, bleeding to death! I burst into our apartment and found Great-Aunt darning Number 2’s cotton socks. She looked up, startled, as I squeezed past her, ducked behind the curtain and plunked myself down on the chamber pot.

“Great-Aunt,” I cried, “I am bleeding to death, just like your cousin!”

“What are you talking about, Ah Si?” Through a gap in the curtain I noted that she hadn’t even looked up from her mending.

“I have blood all over my pants and it’s still coming!” I yelled. What’s wrong with her? I thought. Can’t she see I’m sick?

Finally she put down the sock and needle and slowly rose to her feet, mumbling.

“What did you say?” I shouted, exasperated by her apparent calm.

“I really don’t know what to tell you,” she said, opening a dresser drawer. “It should be a mother’s job to explain this.”

I hated it when she talked like that. Whenever I got on her nerves, she wouldn’t criticize me. Instead, she would blame Mother for spoiling me. If I complained about the ugliness of my clothes, she would say I had Mother’s vanity in my blood. I had given up arguing years ago; she always got the last word.

Now here we go again, I thought. I’m dying and she makes remarks about my poor dead mother.

“Why can’t you leave Mother alone? At least you’re still alive.”

I yanked the curtain closed, expecting her to criticize me for my outburst. But she brought me a small paper parcel and a square brown package with “Sanitary Paper” written on all four sides. Her lack of concern calmed me somewhat and I examined the parcel. I had seen ones like it in store windows and had often wondered why there were two kinds of toilet paper, one called straw paper—an accurate description, since smashed straw pieces made a wrongful appearance here and there—and the other sanitary paper, which was sold in glued packages rather than stacks. Now that I thought of it, I had also seen it from time to time in our toilet paper basket at home.

But why was Great-Aunt handing me this stuff when I was in such danger? My very life was flowing down my legs.

I recalled what the doctor had told us when he had diagnosed Mother’s terminal cancer: “Let her eat what she likes.” Was that why Great-Aunt was giving me such fancy toilet paper?

I turned the second packet over in my hand. “Sanitary Belt,” it read. I thought, double sanitation. Inside was a pink belt-like contraption, shaped like the letter T, made of soft rubber with white cotton bands.

“What’s this?” I called out to Great-Aunt, who had returned to her work. “Why are you giving me these instead of pills?”

“Are you really as stupid as you sound? Can’t you read?”

“Of course I can, but there’s nothing here to tell me what they’re for!”

“Don’t try to fool me. I may not know how to read, but I can see there are words all over the packages,” she insisted.

Knowing I had already gone too far, I softened a bit. Besides, I knew I could be left in this position all day if I opened my mouth again. In a moment Great-Aunt came back and showed me how to fit the paper inside the belt.

“Believe me, you are not going to die. Your parents wouldn’t let that happen to you.”

I put the strange contraption on and waited for Number 3 to come home for lunch. She went to a different school because of her entrance exam results. Maybe I could get some answers as well as sympathy from my elder sister.

“Number 3! I thought I was going to die this mor—”

“Cut your voice down, Ah Si,” Great-Aunt interrupted.

“What happened?” Number 3 asked.

I dragged her into the front room. “I have gastric bleeding, just like Great-Aunt’s cousin. You can’t imagine what a mess I made in the classroom.”

Before I could go on, my sister pushed me away. “It’s a pity you only look smart,” she sneered. “Didn’t you read your health textbook?” She walked out of the room, muttering, “Dying! As if there isn’t enough death in this family already.”

Physiological Hygiene was a non-credit course at my school. We had one lecture a week and were supposed to study the textbook ourselves. But the lectures were often cancelled to make time for political study sessions, and I had avoided the book ever since a girl in my class had been accused of having dirty thoughts when she was spotted looking at the pictures of a naked man and woman.

That afternoon I hunted up the book. By the time I had finished reading it, I was weeping, for the relevant section emphasized that students should read it “under parental guidance.”

I felt Great-Aunt’s hand on my shoulder. “Don’t be sad, Ah Si. Every girl has to go through this, and believe it or not, some parents are happy for their daughters when it happens.”

“The book says it’s a mother’s job to tell things like this to their daughters,” I said without looking at her. “But Mother is gone. Who is going to tell me all the rest of the things I don’t know?”

“Ah Si, I’ll try, if you let me. I’ll do my best to raise you, even though I’m not sure how.”

I now felt sorry for the words I had thrown at her earlier.

Probably nobody had ever told Great-Aunt herself about menstruation. And I was sure there had been no book available for her, even if she had been able to read. Considering her own life, how could she say that for a young girl to become a woman was a joy?

The harmony we had reached was short-lived, though. Before supper time I asked her for another package of sanitary paper.

“Are you saying you used it all in less than half a day?” She sounded more shocked than angry.

“Well, I didn’t eat it! It’s paper, you know, not candy.”

“Each package costs thirty cents,” she rebuked me as she showed me how to extend the life of the paper by refolding it for a second use. “That was half a day’s pay for your brother when he was an apprentice.”

How nice it would be if there was just one thing in life that didn’t involve money. Only a few days before, she had been complaining loudly about the rise in food prices. How could she save money for our winter clothes? I pictured our money flying away with all the sanitary paper for Number 3, Great-Aunt and me. One day Number 5 would need it too.

I sighed. “Great-Aunt, wouldn’t it be wonderful if we were all boys?”

One dusty and windy afternoon toward the end of May, fifty classmates and I rode the bus for an hour and a half into

Songjiang County to the Eastern Town Brigade. Although my visits to Grandfather’s rural town had made me familiar with country living, I was nervous and confused. We had been sent there to help with the Three Summer Jobs, a policy that had more to do with politics than logic, and I had no idea how we city girls could help the peasants. In the space of two weeks we were supposed to learn planting, harvesting and field management, and to grow physically and mentally fit from hard labour. We were housed in a large building with a swept dirt floor. Along the walls, rice straw had been strewn over planks for our beds. I dropped my bedroll onto the boards and started to unpack.

It turned out that there was not as much “real work” as we had been led to expect. First, we picked up loose ears of wheat in the fields and along the roads, an easy but tremendously tedious job. A few days later, we carried bundles of rapeseed stalks, which had been harvested and tied loosely with straw. Since the seed pods were crisp and fell off easily, great care was needed when transporting them to the threshing ground. The farmers instructed us to carry one bundle at a time, but we all burst out laughing after lifting them up: the large, awkward bundles seemed weightless. Ignoring the expert advice, we left with one bundle in each hand, struggling over the ridges in the plowed fields. A strong wind buffeted the bundles like kites, pulling me this way and that until I lost balance and fell to the dirt. Rapeseed scattered and rolled all around me. By the end of the day at least five of us had sprained our ankles.

Some villagers didn’t hide their feelings about the whole business of having incompetent city kids around, calling our mission “lighting a candle for a blind person,” and all of us eagerly awaited the day when we could go home. When we stepped down from the bus into our schoolyard two weeks later I felt we had not gained much except our bundles of dirty laundry. Principal Lin welcomed us back with a long boring speech, during which he constantly consulted his notebook as we stood baking in the sun.