My Secret Diary (3 page)

Authors: Jacqueline Wilson

Everyone cordially hated the summer uniform:

canary-yellow dresses in an unpleasant synthetic

material. There is not a girl in existence who

looks good in canary yellow. It makes pale girls

look sallow and ill, and rosy-cheeked girls

alarmingly scarlet. The dresses had ugly cap

sleeves, like silly wings, unflattering to any kind

of arm and embarrassing when you put up your

hand in class.

Very few people had washing machines in those

days. You did your main wash once a week, so by

Friday our canaries were stained and dingy. We had

to wear straw boaters going to and from school

even if there was a heatwave. These were hard,

uncomfortable hats that made your head itch. They

could only be kept in place with elastic. Nasty boys

would run past and tip our boaters so that the

elastic snapped under our chins.

Particularly

nasty

boys would snatch at our backs to twang our

bra elastic too. I often wonder

why

I wanted

a boyfriend!

I looked younger than my age in my school

uniform, but I did my best to dress older outside

school – sometimes for particular reasons!

Thursday 4 February

After school I went to the pictures with Sue and

Cherry. I wore my red beret, black and white coat

and black patent shoes and managed to get in for

16 as the picture was an 'A'.

I sound too twee for words. A beret? But at least

it was a change from eau de nil. Green still figured

prominently in my wardrobe though.

Saturday 12 March

In the afternoon I went shopping with Mummy and

we bought me a pale green checked woolly

shirtwaister for the Spring to go with my green

shoes and handbag.

Just call this the lettuce look. However, I seemed

to like it then. In May I wrote:

After dinner I got dressed in my new green

shirtwaister, that I think suits me very well. Then,

loaded down with records, I called for Sue and we

went to Cherry's party. Everyone had brought lots

of records, and did my feet ache after all that jiving!

Carol wore her new black and white dress which

looked nice.

My writing was certainly as limp as a lettuce in

those days.

Nice!

So I liked my green dress, but my favourite outfit

was 'a cotton skirt patterned with violets and nice

and full'. It's about the only one of those long-ago

garments I wouldn't mind wearing now on a

summer day.

Biddy was generous to me, buying me clothes

out of her small wage packet.

Saturday 4 June

In the afternoon Mummy and I went to Richmond

and after a long hunt we bought me a pair

of cream flatties, very soft and comfortable.

Then, back in Kingston, we went into C & A's and

found a dress in the children's department

that we both liked very much. The only trouble

with it was that it had a button missing at the

waist. Mummy made a fuss about it, but they

didn't have another dress in stock or another

button, so we bought it minus the button as we

liked it very much indeed. It is a lovely powder

blue colour with a straight skirt and Mummy

has transferred the bottom button to the waist so

that it doesn't notice so much.

I sound like little Goody-Two-Shoes, trotting

round with Mummy, being ever so grateful for my

girly frock. It's reassuring to see that I revert to

surly teenager the very next day.

Sunday 5 June

I AM A PIG

.

I was rude and irritable today and I

just didn't care, and I spoilt Mummy's day at the

coast. (Daddy wasn't very well-behaved either

though!) I won't write any more about a very

unfortunate day.

I wish I had. It would have been a lot more

interesting than painstaking accounts of buttons

missing on powder-blue dresses!

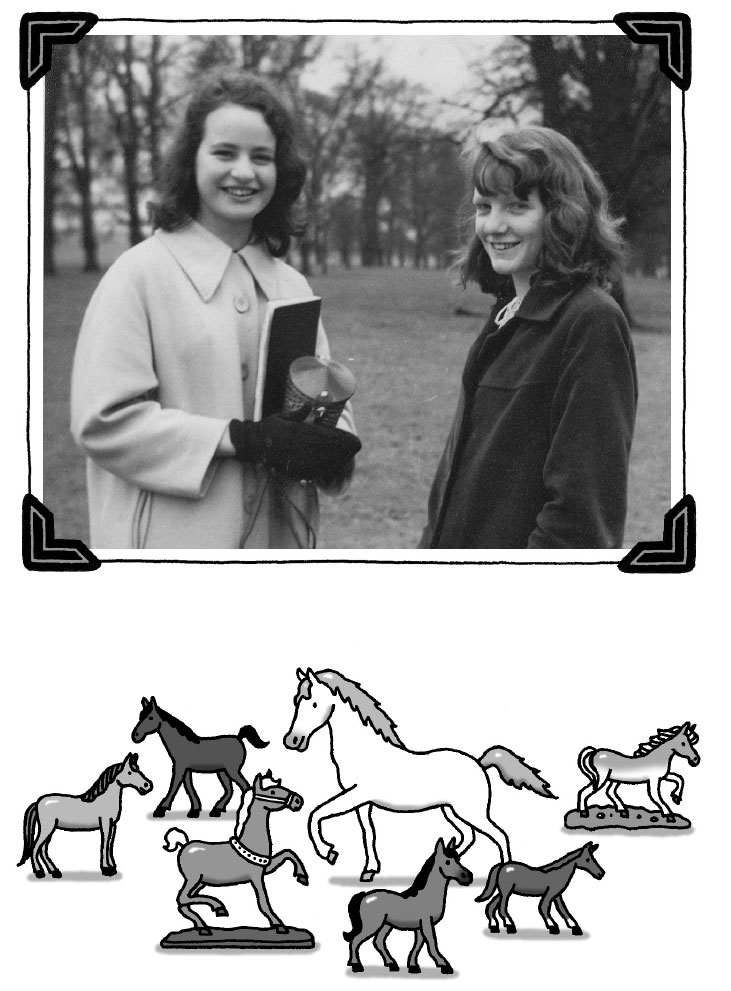

Chris

Sunday 3 January

Chris and Carol are my best friends, and there is

also Sue who lives next door, and Cherry down the

road. They all go to Coombe, my school.

I met my very special friend, Chris, on my first

day at Coombe County Secondary School for Girls.

I'd had

another

Christine as my special friend when

I was at primary school but we'd sadly lost touch

when we both left Latchmere. I think she moved

away after her mum died.

I'd never set eyes on my new friend Chris

before that first day at secondary school. I

didn't know anyone at all. It's always a bit scary

going to a brand-new school. Coombe was in New

Malden, two or three miles from our flats in

Kingston. I hadn't made it through my eleven plus

to Tiffin Girls' School, but I'd been given a 'second

chance' and managed to pass this time. I could

now go to a new comprehensive school instead of

a secondary modern.

Coombe was one of the first comprehensives,

though it was divided firmly into two teaching

streams – grammar and secondary modern. In an

effort to make us girls mix in together, we were

in forms for non-academic lessons like singing

and PE, and in groups graded from one all

the way to nine for lessons like maths and

English. This system didn't make allowances for

girls like me. I'd been put in group one, where I

held my own in English and most of the arts

subjects – but I definitely belonged in group

nine for maths! Still, compiling that timetable

must have been nightmare enough without

trying to accommodate weird girls like me – very

good in some subjects and an utter dunce

in others.

I couldn't even get my head around the densely

printed timetable, and the entire geography of the

school was confusing. We weren't shown around

beforehand or even given a map when we arrived

the first day. We were somehow expected to

sense

our way around.

I managed to fetch up in the right form room,

1A. We stood around shyly, eyeing each other up

and down. We were a totally mixed bunch. A few

of the girls were very posh, from arty left-wing

families who were determined to give their

daughters a state education. Some of the girls were

very tough, from families who didn't give their

daughters' education a second thought. Most of us

were somewhere in the middle, ordinary suburban

girls fidgeting anxiously in our stiff new uniforms,

wondering if we'd ever make friends.

'Good morning, Form One A! I'm Miss Crowford,

your form teacher.'

'Good-morning-Miss-Crowford,' we mumbled.

She was small and dark and quite pretty, so we

could have done a lot worse. I hoped she might

teach English, but it turned out she was the gym

teacher. I started to go off her immediately, though

she was actually very kind and did her best to

encourage me when I couldn't climb the ropes and

thumped straight

into

rather than over the

wooden horse.

Miss Crowford let us choose our own desks. I

sat behind a smallish girl with long light-brown

hair neatly tied in two plaits. We all had to say our

names, going round the class. The girl with plaits

said she was called Christine. I was predisposed to

like

girls called Christine so I started to take proper

notice of her.

Miss Crowford was busy doing the Jolly-Teacher

Talk about us being big girls now in this lovely

new secondary school. She told us all about the

school badge and the school motto and the school

hymn while I inked a line of small girls in

school uniform all round the border of my new

and incomprehensible timetable.

Then a loud electronic bell rang, startling us.

We were all used to the ordinary hand-bells rung

at our primary schools.

'Right, girls, join your groups and go off to

your next lesson,' said Miss Crowford. 'Don't

dawdle! We only give you five minutes to get to the

next classroom.'

I peered at my timetable in panic. It seemed to

indicate that group one had art. I didn't have a

clue where this would be. All the other girls were

getting up purposefully and filing out of the room.

In desperation I tapped Christine on the back.

'Excuse me, do you know the way to the art

room?' I asked timidly.

Chris smiled at me. 'No, but I've got to go there

too,' she said.

'Let's go and find it together,' I said.

It took us much longer than five minutes. It

turned out that the art room wasn't even in the

main school building, it was right at the end of the

playground. By the time we got there I'd made a

brand-new best friend.

Coombe had only been open for two years, so

there weren't that many girls attending, just us

new first years, then the second and third years.

We barely filled half the hall when we filed into

assembly. It was a beautiful hall, with a polished

parquet floor. No girl was allowed to set foot on it

in her outdoor shoes. We had to have hideous rubber-soled

sandals so that we wouldn't scratch the shiny

floorboards. We also had to have black plimsolls for

PE. Some of the poorer girls tried to make do with

plimsolls for their indoor shoes. Miss Haslett, the

head teacher, immediately protested, calling the

offending girls out to the front of the hall.

'They are

plimsolls

,' she said. 'You will wear

proper indoor shoes tomorrow!'

I couldn't see what possible harm it would do

letting these girls wear their plimsolls. Why were

they being publicly humiliated in front of everyone?

It wasn't their fault they didn't possess childish

Clarks sandals. None of us earned any money. We

couldn't buy our own footwear. It was a big struggle

for a lot of families to find three pairs of shoes for

each daughter –

four

pairs, because most girls

wouldn't be seen dead in Clarks clodhoppers

outside school.

However, the next day all the girls were wearing

regulation sandals apart from one girl, Doreen, in

my form. She was a tiny white-faced girl with bright

red hair. She might have been small but she was

so fierce we were all frightened of her. Doreen

herself didn't seem frightened of anyone, not even

Miss Haslett.

Doreen danced into school the next day, eyes

bright, chin up. She didn't flinch when Miss Haslett

called her up on the stage in front of everyone.

None of Doreen's uniform technically passed

muster. Her scrappy grey skirt was home-made and

her V-neck jumper hand-knitted. She wore droopy

white socks – and her black plimsolls.

Miss Haslett pointed at them in disgust, as if

they were covered in dog's muck. 'You are still

wearing plimsolls, Doreen! Tomorrow you will

come to school wearing

indoor shoes

, do you

hear me?'

Doreen couldn't help hearing her, she was

bellowing in her face. But she didn't flinch.

We all wondered what would happen tomorrow.

We knew Doreen didn't

have

any indoor shoes, and

she didn't come from the sort of family where her

mum could brandish a full purse and say, 'No

problem, sweetheart, we'll trot down to Clarks

shoeshop and buy you a pair.'

Doreen walked into school assembly the next

morning in grubby blue bedroom slippers with

holes in the toes. I'm certain this was all she had.

She didn't look as if she was being deliberately

defiant. There was a flush of pink across her pale

face. She didn't want to show off the state of her

slippers to all of us. Miss Haslett didn't understand.

She flushed too.

'How

dare

you be so insolent as to wear your

slippers in school!' she shrieked. 'Go and stand

outside my study in disgrace.'

Doreen stood there all day long, shuffling from

one slippered foot to the other. She didn't come

into school the next day. The following Monday she

wore regulation rubber-soled school sandals. They

were old and scuffed and had obviously belonged

to somebody else. Maybe someone gave them to

her, or maybe her mum bought them for sixpence

at a jumble sale.

'At last you've seen sense, Doreen,' said Miss

Haslett in assembly. 'I hope this has taught you all

a lesson, girls.'

I

hadn't seen sense. I'd seen crass stupidity

and insensitivity on Miss Haslett's part. It

taught me the lesson that some teachers were

appallingly unfair, so caught up in petty rules and

regulations that they lost all compassion and

common sense.

A couple of years later

I

ended up standing in

disgrace outside Miss Haslett's study door. She'd

seen me walking to the bus stop without my school

beret and – shock horror! – I was sucking a Sherbet

Fountain. I'd committed not one but two criminal

offences in her eyes: eating in school uniform and

not wearing my silly hat.

Miss Haslett sent for me and started telling me

off. 'Why were you eating that childish rubbish,

Jacqueline?' she asked.

The obvious answer was that I was hungry,

and I needed something to keep me going for the

long walk home. (I'd stopped taking the bus after

the dramatic accident.) However, I sensed Miss

Haslett would consider an honest answer insolent,

so I kept quiet.

'And

why

weren't you wearing your school

beret?' she continued.

This was easier. 'I've lost it, Miss Haslett,' I

said truthfully.

It had been there on my coat hook that morning.

Someone had obviously snatched it for themselves

when their own beret had gone missing.

'That's just like you, Jacqueline Aitken,' said

Miss Haslett. 'Stand outside!'

I stood there. My legs started aching after

a while so I leaned against the wall. I didn't feel

cast down. I was utterly jubilant because I was

missing a maths lesson. I gazed into space and

started imagining inside my head, continuing

a serial – a magic island story. Pupils squeaked

past in their sandals every now and then, good

girls trusted to take important messages to Miss

Haslett. The odd teacher strode past too, several

frowning at me to emphasize my disgrace. But then

dear Mr Jeziewski, one of the art teachers, came

sloping along in his suede shoes. He raised

his eyebrows at me in mock horror, felt in his

pocket, put two squares of chocolate on the window

ledge beside me and winked before he went on

his way.

I smiled at Mr Jeziewski and savoured my

chocolate. I couldn't resist writing a similar scene

in my book

Love Lessons

, in which my main girl,

Prue, falls passionately in love with her art teacher,

Mr Raxbury. I promise I

didn't

fall for Mr

Jeziewski, who was very much a family man and

rather plain, with straight floppy hair and baggy

cords – but he was certainly my favourite teacher

when I was at Coombe.

Having Chris for a friend was an enormous help

in settling into secondary school life. She wasn't

quite as hopeless as me at PE, but pretty nearly,

so we puffed along the sports track together and

lurked at the very edge of the playing field,

pretending to be deep fielders.

We managed to sit next to each other in maths

lessons so they were almost enjoyable. We didn't

learn

anything, though our teacher, Miss

Rashbrook, was very sweet and gentle and did her

best to explain – over and over again. I could have

put poor Miss Rashbrook on a loop and played her

explanation twenty-four hours a day, it would have

made no difference whatsoever.

Chris and I pushed our desks close and tried to

do our working out together – but mostly we

chatted. We daydreamed about the future. We

decided we'd stay friends for ever. We even wanted

to live next door to each other after we got married.

We could see the row of neat suburban houses

outside the window and picked out two that were

ours. (I had private dreams of a more Bohemian

adult life, living romantically in a London garret

with an artist – but wondered if I could do that at

the weekends and settle down in suburbia Monday

to Friday.)

We don't live next door to each other now but

we

did

stay great friends all through school and

went on to technical college together. We used to

go dancing and I was there the evening Chris met

her future husband, Bruce. I was there at Chris's

wedding; I was there – in floods of tears – at Bruce's

funeral. We've always written and phoned and

remembered each other's birthdays. We've been on

several hilarious holidays, giggling together as if

we were still schoolgirls.

Chris lived in New Malden so she went

home for dinner, and at the end of school she

walked one way, I walked the other, but the rest of

the time we were inseparable. Chris soon asked me

home to tea and this became a regular habit.

I

loved

going to Chris's house. She had a

storybook family. Her dad, Fred Keeping, was a

plumber, a jolly little man who called me Buttercup.

He had a budgie that perched on his shoulder and

got fed titbits at meal times. Chris's mum, Hetty,

was a good cook: she made Victoria sponges and

jam tarts and old-fashioned latticed apple pies. We

always had a healthy first course of salad, with

home-grown tomatoes and cucumber and a little

bit of cheese and crisps. I had to fight not to be

greedy at the Keepings. I could have gone on

helping myself to extra treats for hours. Chris's

sister, Jan, was several years older and very clever

but she chatted to me as if she was my friend too.

We were all passionate about colouring. Chris and

Jan shared a magnificent sharpened set of Derwent

coloured pencils in seventy-two shades.

After Mrs Keeping had cleared the tea things

and taken the embroidered tablecloth off the green

chenille day cloth, we three girls sat up at the table

and coloured contentedly. We all had historical-costume

colouring books. Jan had the Elizabethans

and coloured in every jewel and gem on Queen

Elizabeth's attire exquisitely. Then she settled

down to all her schoolwork while Chris and I went

up stairs. We were supposed to be doing

our

homework up in Chris's bedroom, but we muddled

through it as quickly as possible.