My Secret Diary (2 page)

Authors: Jacqueline Wilson

My Family

We were a small family, just Biddy, Harry and

me, cooped up in our claustrophobic council

flat in Kingston. There were a lot of arguments.

Biddy and me, Harry and me, Biddy and Harry

against me – and, most frequently of all, Biddy and

Harry arguing between themselves.

I rarely go into details of these arguments in my

1960 diary. I just write at the bottom of many pages:

'Mummy and Daddy had a row.' These rows could

blow up over the silliest things. Harry might moan

about the way Biddy tucked his socks into a tight

ball, or Biddy might raise her eyebrows and sniff

in a snobbish way if Harry said, '

Pardon?

'. These

tiny irritations would be like a starter's gun.

Suddenly they were

off

– and the row would escalate

until they were both shouting at the tops of

their voices.

'For God's sake, what will the neighbours

think?' Biddy would hiss when Harry was in mid

rant. Harry would bellow that he couldn't care less

about the neighbours – or words to that effect.

The Grovers at number eleven and the Hines at

number thirteen must have sighed and turned up

their televisions, muttering 'Those dreadful

Aitkens' again.

Yet it wasn't

all

rows and ranting. Biddy and

Harry couldn't stand each other, and like all

teenagers I sometimes felt I couldn't stand them –

but we could still have fun together. On Sunday

mornings, if Harry was in a good mood, he'd get up

and make us breakfast. We weren't healthy eaters

then. My absolute favourite Sunday-treat breakfast

was fried potatoes on buttered toast, followed by

another piece of toast spread with thick white

sugary condensed milk. My mouth is puckering as

I write this. Nowadays I couldn't swallow so much

as a teaspoon of ultra-sweet condensed milk to save

my life, but when I was fourteen I could have

slurped up a whole tin at a time.

We ate a large Sunday roast together too while

listening to

The Billy Cotton Band Show

and

Family Favourites

on the radio. We particularly

enjoyed listening to

Hancock's Half Hour

as a

family, all three of us convulsing with laughter. We

watched television together in the evenings. For a

long time we only had one television channel so

there weren't any arguments about which

programme to pick.

There must have been many ordinary cosy

evenings like this:

Thursday 3 March

I'm sitting at the table. The time is twenty to eight.

'Life of Bliss' is on the T.V. Daddy has just got in

from work. I ask Mummy what happened at her

office. Mr Lacy was in a good mood, she replies,

and goes back to her newspaper. What are you

looking for? Mummy asks Dad. My black pen, he

replies, have I got time for a bath before supper?

Only an in and out says Mummy. Daddy has his

bath. We sit down to our supper of macaroni cheese

(one of my favourites). After supper I do my maths

homework. Daddy helps, bless him. Then I watch

T.V. It is a Somerset Maugham play, and very good.

P.S. Mum bought me some sweet white nylon

knickers.

I was still very close to Biddy and struggled hard

to please her. I took immense pains to find an

original Mother's Day present for her. I went

shopping in Kingston with my friends Carol and

Cherry, all of us after Mother's Day presents –

though we got a little distracted first.

We first went to Maxwells the record shop, and I

bought the record 'A Theme from a Summer Place'.

It was lovely. Then we went to Bentalls. First we

went to the Yardley make-up, and a very helpful

woman sold me my liquefying cleansing cream and

Cherry a new lipstick. Then we bought our mothers

some cards, and Cherry bought her mother some

flowers, and Carol bought her mother some chocs.

But I knew what I wanted for my adorable, queer,

funny, contemporary mother. A pair of roll-on black

panties, a pair of nylons and a good (expensive)

black suspender belt.

I record happily on Sunday: '

Mum was very

pleased with her panties, belt and nylons

.'

I tried to please Harry too. I didn't buy him a

vest and Y-fronts for Father's Day, thank goodness

– but I did make an effort.

Saturday 4 June

I bought a card for Father's Day, and some men's

talcum and three men's hankies as well.

Biddy and Harry bought me presents too,

sometimes vying with each other, to my advantage:

'Biddy gave me a pound to spend for when I'm

going round Kingston with Carol – and then Harry

gave me five pounds. For nothing!!!'

They could be imaginative with gifts. Biddy not

only bought me all my clothes, she bought me books

and ornaments and make-up. Harry tried hard too.

He was away up in Edinburgh for a week on

business (I wrote, 'It feels so strange in the flat

without Daddy'), but when he came back he had

bought lavish presents for both of us:

Saturday 21 May

Daddy came back from Scotland today. He gave me

a little Scotch doll, a typewriter rubber, a coin

bracelet, an expensive bambi brooch, and a little

book about Mary, Queen of Scots. He gave Mummy

a £5 note.

Harry could be generous with his time too. That

summer of 1960 I had to do a Shakespeare project

so he took a day off work and we went to Stratford.

It was a

good

day too. We went round Shakespeare's

birthplace and Anne Hathaway's cottage and

collected various postcards and leaflets. My project

was the most gorgeously illustrated of anyone's.

But he mostly kept to himself, out at work on

weekdays, still playing tennis at the weekends, and

when he was at home he hunched in his armchair,

surrounded by piles of

Racing Posts

and form

books. If he wasn't going out he rarely bothered to

get dressed, comfortable in our centrally heated flat

in pyjamas and dressing gown and bare feet.

Biddy frequently changed into her dressing gown

too and sat watching television, tiny feet tucked up,

her Du Maurier cigarettes on one arm of the chair

and a bag of her favourite pear drops on the other.

As the evening progressed, one or other of them

would start nodding and soon they would both be

softly snoring. I'd huddle up with my book, happy

to be left in peace way past my bed time.

They never went out in the week but they

started going out on Saturday nights with Biddy's

friend Ron. They must have been strange evenings,

especially as my parents were practically teetotal.

Biddy stuck with her bitter lemons. Harry tried a

pint of beer occasionally but hated it. One Saturday

night he pushed the boat out and had two or three

and came home feeling so ill he lay on the kitchen

floor, moaning.

'Well, it's all your own fault, you fool. You were

the one who poured the drink down your throat,'

said Biddy, poking him with her foot.

Harry swore at her, still horizontal.

'Don't you start calling me names! Now get up,

you look ridiculous. What if someone walks along

the balcony and peers in the kitchen window?

They'll think you're dead.'

'I wish I was,' said Harry, and shut his eyes.

I don't think he enjoyed those Saturday nights

one iota – and yet he agreed to go on a summer

holiday that year with Ron and his wife, Grace. I

don't know if Harry had any particular secret lady

friends at that time – he certainly did later on in

his life. I think Biddy and Harry came very close

to splitting up when I was fourteen or so. I know

Ron had plans to go to Africa and wanted Biddy to

go with him. But I was the fly in the ointment,

flapping my wings stickily. Biddy wouldn't leave

me, so

she

was stuck too.

We went out very occasionally on a Sunday

afternoon, when we caught the bus to the other

end of Kingston and went to tea with my

grandparents, Ga and Gongon. The adults played

solo and bridge and bickered listlessly and ate

Cadbury's Dairy Milk chocolates. I ate chocolates

too and curled up with my book. If I finished my

own book I read one of Ga and Gongon's Sunday

school prize books or flipped through their ten

volumes of Arthur Mee's

Children's Encyclopedia

.

I preferred visiting Ga by myself. I'd go on

Wednesday afternoons after school. She'd always

have a special tea waiting for me: thinly sliced bread

and butter and home-made loganberry jam, tinned

peaches and Nestlé's tinned cream, and then a cake

– a Peggy Brown lemon meringue tart if Ga had

shopped in Surbiton, or a Hemming's Delight

(meringue and artificial cream with a glacé cherry)

if she had been to Kingston marketplace.

Ga would chat to me at tea, asking me all about

school, taking me ultra seriously. I should have

been the one making

her

tea as her arthritis was

really bad now. She had to wear arm splints and

wrist supports, and for a week or so before her

monthly cortizone injection she could only walk

slowly, clearly in great pain. It's so strange realizing

that Ga then was younger than me now. She looked

like an old lady in her shapeless jersey suits and

black buttoned shoes.

One Wednesday it was pouring with rain and I

was sodden by the time I'd walked to Ga's, my hair

in rats' tails, my school uniform dripping. Ga gave

me a towel for my hair and one of her peachy-pink

rayon petticoats to wear while my clothes dried.

But when it was time for me to go home they were

still soaking wet. I didn't particularly mind but Ga

wouldn't hear of me walking the three quarters of

an hour home up Kingston Hill in sopping wet

clothes. She was sure I'd catch a chill. She insisted

I borrow one of her suits. She meant so well I

couldn't refuse, though I absolutely died at the

thought of walking home in old-lady beige with her

long sagging skirt flapping round my ankle socks.

Ga could no longer make her own clothes

because her hands had turned into painful little

claws due to her arthritis – but she would press

her lips together firmly and

make

herself sew if it

was for me.

Wednesday 27 January

After school went up to Ga's. She has made my

Chinese costume for the play, and also gave me a

lovely broderie anglaise petticoat. Isn't she kind?

Yes, she was

very

kind, in little sweet ways. On

14 February I always received a Valentine. That

year it was two little blue birds kissing beaks,

perching on two red hearts outlined with glitter.

There were forget-me-nots and roses sprinkled

across the card, and inside a little printed verse

and an inked question mark. I knew it wasn't from

a boy, although I was supposed to assume it came

from a secret admirer. I was pretty certain it was

Ga wanting to give me a surprise, sending me a

Valentine so I could show it off at school.

She was always so reassuring and comforting.

Wednesday 24 February

Back to school, worst luck. Going to school all

Wolverton Avenue was dug up and there were many

workmen standing around and digging under the

pavement. Sue at once crossed the road, but I stayed

on the left side where they were working and each

time they smiled and said hello and how are you,

etc. in the friendly way workmen do, I smiled back

and said hello, and I feel fine. Afterwards Sue was

ever so crabby and said in what I call her 'old maid'

voice, 'I saw you smile at all those work men.' Talk

about a bloody snob! She makes me MAD at times.

I told Ga when I went up there this afternoon after

school and she (the darling) said I had a nice little

face and naturally they would smile and talk to me,

and that it was only polite that I should do the

same back.

Ga was so gentle with me, letting me rant on in

a half-baked manner about becoming a pacifist and

banning the bomb and being anti-apartheid, while

she nodded and smiled. I got tremendously steamed

up at the end of term because we were having a

party for all the girls at school, with music and

non-alcoholic punch.

'It's not

fair

!' I said.

'You can't have real punch at a school party,'

she said reasonably.

'Oh no, I don't mind the non-alcoholic punch

part. I don't

like

proper drink,' I said.

She looked relieved. 'So

what

isn't fair?' she asked.

'We can't have boys! Can you imagine it, just us

girls dancing together all evening. That's not a

proper party, it's just like dancing school. We're all

furious, wanting to take our boyfriends.'

Ga blinked. 'So, have you got a boyfriend, Jac?'

'Well . . . no, I haven't, not at the moment. But

that's not the point, it's the

principle

that matters,'

I said, determined not to lose face.

Ga was kind enough not to laugh at me.

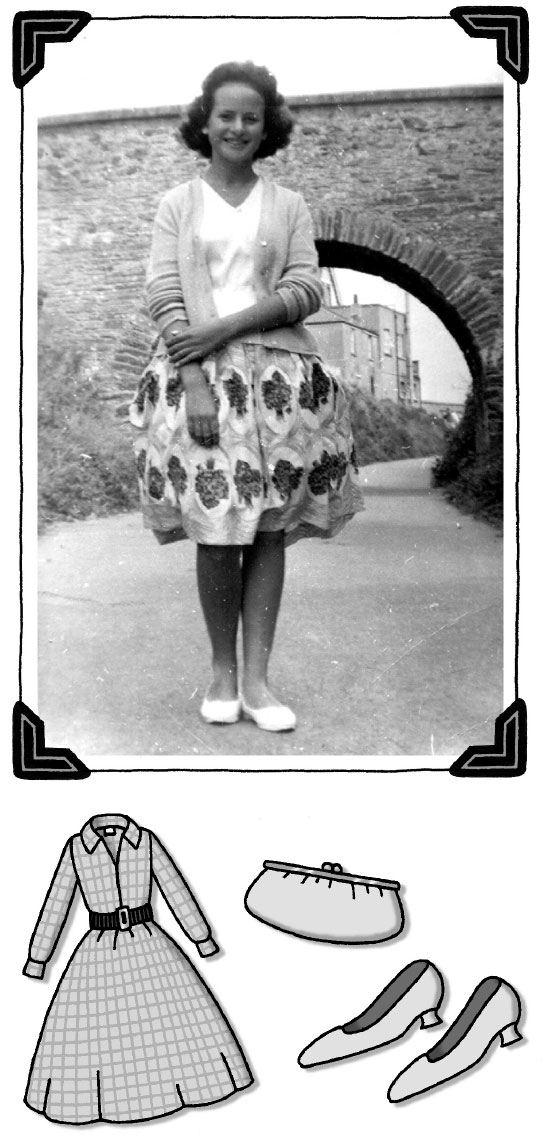

Clothes

Saturday 2 January

I went to Bentalls' sale with Mum. We got some

smashing bargains so I'm jolly glad I went. First

a very full pink and mauve mohair skirt, and to go

with it a lovely pink thick-knit Austrian cardigan.

We got it for 45 bob, but previously it had been

£9.9s!! I also got a good book and a new lipstick. I

tried it out this afternoon and wore my new outfit,

and I think I looked quite nice. I looked warm, cosy

and fashionable, nice and teenager-y, but not

looking too grown up.

I can't believe I once used words like

jolly

and

smashing

! I sound like someone out of Enid

Blyton's Famous Five books. That pink and mauve

mohair skirt and Austrian cardigan sound

absolutely hideous too, though I obviously liked

them at the time. I didn't actually

want

to look

'nice and teenager-y'.

If you wanted to look truly cool in 1960 you

dressed like a Beatnik. You had long straight hair

(sigh!). You wore black: black polo-neck jumper,

black skirt, black stockings, black pointy boots,

with a black duffel coat over the top. You were

probably roasting to death in all these woolly layers

but you

looked

cool. I'd have given anything to be

a Beatnik but it would have looked like fancy dress

on a schoolgirl living on a suburban council estate.

Beatniks were exotic adults who lived in London

and haunted smoky jazz cellars.

The cool look at school was totally different.

Girls backcombed their hair into bouffant styles

and then sprayed it until it hardened into a helmet.

They cinched in their waists with elasticated belts

and stuck out their skirts with nylon petticoats.

You could get wonderfully coloured petticoats at

Kingston Monday market – pink, blue, even bright

yellow, edged with lace. You washed these petticoats

in sugar water, which made them stiff. Your skirts

bounced as you walked, showing your layers of

petticoat. You wobbled when you walked too, in

stiletto heels.

I say 'you'.

I

didn't have bouffant hair,

elasticated belts, flouncy petticoats or stiletto heels.

'You're not going out looking as Common as

Muck,' said Biddy.

I rather wanted to look as Common as Muck,

but I couldn't manage it, even behind Biddy's back.

I didn't know

how

to tease my hair into that

amazing bouffant shape. It was either too frizzy or

too limp, depending on whether I'd just had

another dreaded perm or not.

I didn't have enough of a waist to cinch, and my

petticoats were limp white garments that clung to

my legs. I didn't have proper stilettos. My first pair

of heels were barely an inch high. They were called

Louis heels, squat, stumpy little heels on a slip-on

shoe. I was used to straps or laces and I had to

walk with my feet stuck out like a ballet dancer to

keep them on. They were pale green. 'Eau de nil,'

said Biddy. She bought me a silly little clutch purse

too, also in eau de nil. I had Biddy's pass-me-down

cream swagger coat that year. It draped in an odd

way and had weird wide sleeves. I didn't swagger

in my coat, I slouched, walking with kipper feet in

my silly shoes, clutching the purse.

'You look so ladylike in that outfit,' said Biddy,

smiling approvingly.

Biddy wasn't alone in wanting her daughter to

look ladylike. At school that spring of 1960 we had

a visit from the Simplicity paper-pattern people.

I'd never sewn a garment in my life apart from

a school apron I'd laboured over in needlework,

but I certainly knew my way around the

Simplicity fashion books. I'd been buying them

for years so that I could cut out all the most

interesting models and play pretend games with

them. It was strange seeing familiar dresses made

up, worn by real girls.

Thursday 17 March

We missed Latin today! The fashion people,

Simplicity, had made up some of their teenage

patterns and our girls dressed up in them, and we

had a fashion parade. It was quite good, and our

girls looked quite different, being all posh, and

wearing white gloves, and walking like proper

models. (Only they looked a bit daft.) I didn't mind

the dresses, but I didn't see one I really liked.

Afterwards the lady told us that we should wear

bras to define and shape our figures (we already do

wear them of course), that we should use deodorants

(which I at any rate do), that we should pay

attention to our deportment (which I try to do), that

we should think carefully whether our lipsticks go

with our dresses (which I do) etc., etc

.

Heavens! I might go in for a spot of lipstick coordination

but I certainly didn't want to wear

ladylike

white gloves

. The very last thing in the

world I wanted to look was

ladylike

. At least the

pink of the mohair skirt wasn't pastel, and the skirt

was full enough to bunch out as much as possible.

I could hide my lack of waist under the chunky

cardigan. I expect the lipstick was pink too. Later

on in the sixties make-up changed radically and I'd

wear

white

lipstick and heavy black eye make-up,

but in 1960, when I was fourteen, the 'natural' look

was still in vogue.

I wasn't great at putting on make-up. I rubbed

powder on my face, smeared lipstick on my lips,

brushed black mascara on my lashes and hoped for

the best. It didn't help that I wore glasses. I had to

take them off when I applied my make-up and

consequently couldn't quite see what I was doing.

I've looked through the photo album covering

my teenage years and I can't find a single picture

of me wearing my glasses. I hated wearing them.

I'm not sure contact lenses were widely available

in those days. I'd certainly never heard of them. I

was stuck wearing my glasses in school. I couldn't

read the blackboard without them. I could barely

see the board itself. But

out

of school I kept them

in the clutch bag.

I had to whip them on quick while waiting at a

bus stop so I could stick my hand out for the right

number bus, but the moment I was

on

the bus I'd

shove the glasses back in the bag. I spent most of

my teenage years walking round in a complete haze,

unable to recognize anyone until they were nose to

nose with me. I was clearly taking my life in my

hands whenever I crossed the road. I was an

accident waiting to happen, especially as I made up

stories in my head as I walked along and didn't

even try to concentrate on where I was going.

I was in the middle of an imaginary television

interview one day going home from school.

'Do tell us what inspired you to write this

wonderful novel, Miss Aitken,' the interviewer

asked as I jumped off the bus.

He never got an answer. I stepped out into the

road and walked straight into a car. I was knocked

flying, landing with a smack on the tarmac. The

interviewer vanished.

I

vanished too, losing

consciousness. I opened my eyes a minute or two

later to find a white-faced man down on his knees

beside me, clutching my hand.

'Oh, thank God you're not dead!' he said, nearly

in tears.

I blinked at him. It was almost like one of my

own fantasies. When Biddy or Harry were

especially impatient with me I'd frequently imagine

myself at my last gasp on my deathbed, with them

weeping over me, begging my forgiveness.

'I'm so sorry!' he said. 'It wasn't my

fault

, you

just walked straight in front of me. I braked but I

couldn't possibly avoid you. Where do you hurt?'

'I don't think I actually hurt anywhere,' I said,

trying to sit up.

'No, you shouldn't move! I'd better find a phone

box to call an ambulance.'

'Oh no, I'm fine, really,' I said, getting very

worried now.

I

did

feel fine, though in a slightly dream-like,

unreal way. I staggered to my feet and he rushed

to help me.

'You really shouldn't stand!' he said, though I

was upright now. 'Are your legs all right? And

your arms?'

I shook all four of my limbs gingerly. One of my

arms was throbbing now,

and

one of my legs, but I

didn't want to upset him further by admitting this.

'Yes, they're perfectly OK,' I said. 'Well, thank

you very much for looking after me. Goodbye.' I

started to walk away but he looked appalled.

'I can't let you just walk off! The very least I

can do is take you home to your mother. I want to

explain to her what happened.'

'Oh no, really!'

'I insist!'

I dithered, nibbling my lip. I couldn't think

clearly. Alarm bells were ringing in my head. Biddy

had drummed it into me enough times:

Never get

into a car with a strange man!

But he seemed such

a nice kind strange man, and I was worried about

hurting his feelings.

I tried to wriggle out of his suggestion tactfully.

'My mum isn't

at

home,' I said. 'So you won't

be able to explain to her.

I'll

tell her when she gets

home from work. I promise I'll explain it was all

my fault.'

I went to pick up my satchel. I used the aching

arm and nearly dropped it. I tried to hurry away,

but the aching leg made me limp.

'You

are

hurt, I'm sure you are,' he said. 'Where

does your mother work? I'm driving you there

straight away, and then I'll drive you both to

the hospital.'

I didn't have the strength for any more arguing.

I let him help me into his car. Biddy's workplace,

Prince Machines, was only five minutes' drive

away. If he drove fast in the wrong direction,

intent on abducting me, then I'd simply have to

fling open the car door and hurl myself out. I'd

survived one car accident, so hopefully I'd survive

a second.

Yes, I know. I was mad. Don't anyone ever get

in a car with a stranger under any circumstances

whatsoever.

However, my stranger proved to be a perfect

gentleman, parking the car in the driveway of

Prince Machines, supporting me under the arm,

carrying my satchel on his own back. Biddy looked

out of the office window and saw us approaching.

She shot out of the office and came charging up

to us. 'Jac? What's happened? Who's this? Are you

all right?'

'This is my mum,' I said unnecessarily.

The stranger explained, anxiously asserting

again that it really wasn't his fault.

Biddy didn't doubt him. 'You're so

hopeless

, Jac!

Haven't I told you to look where you're going? You

were daydreaming, weren't you? When will you

learn

?'

I hung my head while Biddy ranted.

'Still, thank goodness you're all right,' she said

finally, giving me a quick hug.

'Well, I'm not quite sure she

is

all right,' said

my rescuer. 'I think she was unconscious for a

minute or two. She seems pretty shaken up. I'm

very happy to drive you to hospital.'

'Oh, for goodness' sake, she's fine. There's no

need whatsoever,' said Biddy. 'Who wants to hang

around the hospital for hours?'

Biddy had once worked there delivering

newspapers to patients and had a healthy contempt

for the place. She always swore she'd never set foot

in the hospital even if she was dying.

She had more authority than me and sent the

stranger on his way. He was kind enough to pop

back the following day with the biggest box of

chocolates I'd ever seen in my life. I'd never been

given so much as a half-pound of Cadbury's Milk

Tray before. I lolled on my bed in my baby-doll

pyjamas all weekend with my giant box beside me.

I'd seen pictures of big-busted film starlets

lounging on satin sheets eating chocolates. I

pretended I was a film star too. I can't have looked

very beguiling: I had one arm in a sling and one

leg was black with bruises from my thigh down to

my toes.

Biddy had had to drag me up to the dreaded

hospital after all. My aching arm became so painful

I couldn't pick anything up and my bad leg

darkened dramatically. We spent endless hours

waiting for someone to tell us that I'd sprained my

arm badly and bruised my leg.

'As if that wasn't blooming obvious,' Biddy

muttered.

At least it got me out of PE at school for

the next couple of weeks, so I didn't have to

change into the ghastly aertex shirt and green

divided shorts.

I cared passionately about clothes, but most of

the time I was stuck wearing my school uniform.

The winter uniform wasn't too terrible: white

shirts, green and yellow ties, plain grey skirts and

grey V-necked sweaters. We had to wear hideous

grey gabardine raincoats, and berets or bowler-type

hats with green and yellow ribbon round the brim.

Earnest girls wore the hats, cool girls wore berets.

We had to wear white or grey socks or pale

stockings kept up with a suspender belt or a 'roll-on'.

Oh dear, underwear was so not sexy in 1960!

Those roll-ons were hilarious. They weren't as

armour-plated as the pink corsets our grannies

wore, but they were still pretty fearsome garments.

You stepped into them and then yanked them up

over your hips as best you could, wiggling and

tugging and cursing. It was even more of a

performance getting out of them at the end of the

day. I'm sure that's why so many girls never went

further than chastely kissing their boyfriends. You'd

die rather than struggle out of your roll-on in front

of anyone. They had two suspenders on either side

to keep up your stockings. Nylons took a sizeable

chunk of pocket money so we mostly wore old

laddered ones to school. We stopped the ladders

running with dabs of pink nail varnish, so everyone

looked as if they had measles on their legs.

We had to wear clunky brown Clarks shoes –

an outdoor and an indoor pair – though some of

the older girls wore heels on the way home if they

were meeting up with their boyfriends. They

customized their uniforms too, hitching up their

skirts and pulling them in at the waist with those

ubiquitous elasticated belts. They unbuttoned the

tops of their blouses and loosened their ties and

folded their berets in half and attached them with

kirby grips to the back of their bouffant hair.

We were younger and meeker and nerdier in my

year and mostly wore our uniform as the head

teacher intended.