My Share of the Task (25 page)

Read My Share of the Task Online

Authors: General Stanley McChrystal

Although coalescing within Fallujah allowed Zarqawi's influence to gestate, his choice to control much of the city was a strategic mistake. He burnished his legitimacy with insurgents, but as our targeting matured over the summer, we stripped his network of a cadre of mid- and senior-level leaders who operated within Fallujah's limits. More important than any losses to his force, however, were the gains to our own. Our UAV-centric approach to targeting in Fallujah was dangerously limited, but the experience forced us to hone our aerial surveillance skills. Those soon proved even more effective when combined with maturing signals, human, and other intelligence disciplines.

Of course, the enemy was more agile than Fallujah reflected and would soon be far more dispersed. Pressuring him across his network would require that our methods of intelligence development become far more efficient, so that we could replicate the process in many locations simultaneously. Small teams of men, in a time span of days or hours, would have to do intelligence collection, planning, and coordination that in June 2004 spanned weeks and consumed the focus of an entire squadron and task force. In April of that year, we ran a total of ten operations in Iraq. Later that summer, in August, we conducted eighteen. In two years, we would average more than three hundred per month, against a faster, smarter enemy and with greater precision and intelligence yield. Getting there would require further revamping our force by pursuing many of the principles that enabled us to destroy the arms hidden inside Big Ben.

As we grew stronger and more agile, however, our enemies grew more ruthless. And Fallujah was just the opening salvo.

| CHAPTER 10 |

Entrepreneurs of Battle

JuneâDecember 2004

I

t was the machine guns and munitions we found in the flatbed of the truck driven by two Iraqi men out of Fallujah that convinced us we needed to strike Big Ben. But in the days before we hit the arms cache on June 19, 2004, a thirteen-year-old boy, whom the drivers had placed in the front seat as a decoy, gave a hint of an even bigger target.

At the outstation in Baghdad, while the two men were detained, task force operators sat with the kid in one of the rooms of the old Saddam-era mansion used by Green for living quarters and an operations center. They gave the thirteen-year-old a cold Coke from their refrigerator and, through a translator, started chatting. When they asked him about the two drivers, the kid explained that he had seen them meet a few days earlier with a very important man. Between sips of soda, the youngster described the meeting as a thirteen-year-old would. The important man arrived and greeted the group of assembled men, including the two drivers. When the important man arrived, everyone was excited to meet him. Making room for the important man, they sat on the floor and shared hot tea. The men in the circle sat quietly and listened to this important visitor, who spoke for a long time.

The thirteen-year-old recounted the important man's speech. He was very enthusiastic, the kid explained, and told the truck drivers and other men to continue what they were doing. Things, the important visitor had said, were going well.

The Green troops looked sideways at one another, and one asked the boy whether he could recognize the important man in a photograph. Oh sure, he said. The operators brought in a big flip book, with rows of pictures but no names, and set it in front of him. After scanning it a few moments, the kid pointed to one of the mug shots. It was an old picture of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi.

“That's him,” he said in Arabic. “I'm sure of it.”

Although told in youthful tones, the young boy's story conveyed a troubling truth that summer: Things were, indeed, going well for the network Wayne Barefoot had warned us about six months before. Even as Zarqawi sowed enmity among many of the Iraqis stuck in Fallujah, his international notoriety continued to grow and, in a phenomenon peculiar to our media age, it brought him recruits from around the world, in turn widening his influence within the local insurgency beyond his minority group of jihadist followers. Meanwhile, through his Jordanian tribal connections in Baghdad and Anbar and his history with Ansar al-Sunnah in the north, he was forging crucial alliances between traditionally antagonistic groups: deeply xenophobic Iraqi Sunnis, insular Kurds, and his foreign Arab fighters. As he became both transnational terrorist and insurgent leader, he positioned himself at the center of that insurgency's constituencies.

*Â Â Â *Â Â Â *

W

hile Al Qaeda's leaders, with whom Zarqawi still had no official partnership, eyed his rise coolly from afar, our side experienced a turnover of leadership.

The veteran diplomat John Negroponte, who had arrived in Iraq in June to be the new U.S. ambassador, became the top civilian when Bremer turned sovereignty over to Iraq and its new prime minister, Ayad Allawi, on June 28, 2004. On the military side, General George Casey, Jr., arrived to replace Ric Sanchez on July 1. George was the first four-star general to command the military coalition, now called Multi-National ForceâIraq. I was glad that I had known him for several years. Our fathers had been classmates at West Point, graduating in 1945, and I vividly remember my mother's reaction when George's father, thenâMajor General Casey, was killed in Vietnam. For my mom, who had stoically endured my father's multiple combat tours, the death of a peer was a jolting reminder that not only young soldiers die.

George, whom I'd worked with on the Joint Staff, was easy to underestimate. Like John Abizaid, he wasn't physically imposing, and he shared John's disarmingly casual demeanor. But while John bounced with a certain swagger and was endearingly sarcastic, George was quieter, more outwardly professional. Although stocky and square-jawed, he had a subdued manner closer to that of a high-school teacher. I wondered how that would play with the Iraqis, to whom he needed to be a symbol of American strength and competence. But I knew that as a captain, George had passed the grueling Green selection process, only to choose instead to remain in the conventional Army. In thirty years I had never heard of another person passing selection and opting not to join the unit. His self-confident decision impressed me.

As these new leaders entered the scene, they came to find TF 714 assuming a larger role in the war. Beginning with the destruction of Big Ben, we were on the offensive against the Sunni insurgency across Iraq, periodically striking targets in Fallujah and tracking Zarqawi's network around the yellow, dusty cinderblock cities of Anbar. This was the early part of what was to become a significant campaign.

That summer, I tried to envision how that campaign would take shape. Strangely, the fight in arid Anbar Province made me think about a desperate sea battle between Admiral Horatio Nelson's British navy and the allied French and Spanish fleet at Trafalgar on October 21, 1805. Early in the famous battle, Nelson was incapacitated. One of the thousands of musket balls fired point-blank between the ships during the battle caught him in the shoulder, detoured through his lungs and ribs into his spine, and

dropped him to the deck. Three hours and fifteen

minutes later he was dead. But his force, outnumbered by thirty-three enemy ships of the line to his twenty-seven, fought on to a decisive victory.

Nelson's force was able to win without him in command because of what had happened long before the first shot was fired. In the years leading up of Trafalgar, Nelson cultivated traditional strengths inherent in the British navy by making technical mastery and a capacity for independence prerequisites for command. His command style then maximized these qualities: His famous instruction to his ship captains before the Battle of Trafalgarâwhich concluded, “

No Captain can do very wrong if he places his ship alongside that of an EnemyӉembodied the value he placed on his subordinate leaders' taking initiative. He sent this guidance confident in their professional competence and in the entrepreneurial hunger he had stoked in them. Napoleon had done just the opposite, prohibiting his commanding admiral from sharing the larger

strategy with the French captains.

Nelson knew that while the plan mattered, ultimately the actions of the captains would determine the outcome. His genius was to organize the force into a lethal machine, bring the enemy to battle on his terms, and then unleash the apparatus on that enemy. Even as Nelson lay dying, his machine ground on to victory.

Although Nelson had been dead for almost two hundred years, I found that we in TF 714 faced a similar challenge. And we began with similar fundamental advantages.

To confront Zarqawi's spreading network, TF 714 had to replicate its dispersion, flexibility, and speed. Over time, “

It takes a network to defeat a network”

became a mantra across the command and an eight-word summary of our core operational concept. But the network didn't yet exist. Building it would prove to be one the largest challenges I faced in my career. It required turning a hierarchical force with stubborn habits of insularity into one whose success relied on reflexive sharing of information and a pace of operations that could feel more frenetic than deliberate.

I knew I was no Lord Nelson, but thinking about what was demanded of him clarified how I could help build, shape, and lead this revamped TF 714.

In command of a dispersed force facing a dispersed enemy, Nelson endowed his low-level leadersâtalented, ardent menâwith the freedom to maneuver, and the fleet was in turn propelled to success by their zeal. Likewise, our units' strict meritocracy demanded professional expertise, and our highly competent members had the confidence and training to operate without detailed instructions or constant supervision. So I came to see my role as setting the conditions where these qualities were stoked and where initiative, creativity, and dedication to the mission were demanded and supported. Our strategy had to be sound, but success would hinge on how well every level in TF 714 executed it.

I would demand commitment, and offer it myself, to a campaign that would at best be long and arduous. I felt that success against Zarqawi would require nightly raids into gritty neighborhoods to systematically dismantle his network and capture insurgents who hardly appeared to be high-value targets. To many in the elite units, and to some critics outside the command, these less glorious tasks were better left to police or conventional military forces. Inevitably, our campaign would lead to more graveside gatherings in Arlington. Preparing the force and seeking their devotion was ultimately my responsibility but would only be possible through the efforts of leaders across the command. Like Nelson's officers, they would have to stand tall on the deck under fire, leading with competence but also with courage.

And, although we rarely talked of it, we knew we could fail.

*Â Â Â *Â Â Â *

E

arly on, TF 714 lacked a clear mandate to either build a network or get other organizations to join it. Already critics in different parts of the U.S. government felt we were straying outside our traditional roleâwhich we were. But I saw no other organization weaving the kind of web that was needed, and I received strong encouragement from leaders like John Abizaid.

The network I sought to build needed not just physical breadth but also functional diversity. This required the participation of the U.S. government departments and agencies that were involved in counterterrorism, like State, Treasury, the CIA, and the FBI. But we faced a circular dilemma: Because their participation was essentially voluntary, TF 714 needed to be more effective at targeting Al Qaeda for other agencies to want to join our project. But we often needed their support or compliance to be noticeably more effective. The solution, I realized, was to do what we could to improve TF 714 internally to make us more appealing to partners. We began by rewiring TF 714's units into a network better connected to itself and more accommodating to those agencies we were courting.

To do so, and to posture TF 714 for a more decisive role to defeat Zarqawi's network, we needed a central hub with a clean deck. In July 2004, amid plans to give control of Baghdad International Airport (BIAP) back to the newly sovereign Iraq, we found that new hub at a former Iraqi air base in Balad, a rural area west of the Tigris, almost fifty miles north of Baghdad.

American forces had occupied the base since the invasion, but the temporary infrastructure reflected the initial Coalition mindset: Get in quickly; get out just as fast. When I visited our sectionâa dusty area in the northwest corner, crisscrossed by cement roads and runwaysânothing usable remained. For security and secrecy, we walled off our plot with concrete blocks and rock-filled HESCO barriers. Across the airfield, on the other side of its two large runways, Coalition forces occupied tents and Saddam-era buildings. Over time, that area sprouted retail shops and several fast-food restaurants housed in small trailers. But our plot remained spartanâwhich I considered essential to our focus. Lieutenant Colonel Richard Williams, who commanded the British Special Air Service task force later in the war, captured the atmosphere inside our compound vividly: “We were there to fight, to do PT, to eat, to sleep, then to fight again. There was no big-screen TV or other diversion in the barracks. It was a world of concrete, plywood, and gun oil, and it was

absolutely intoxicating in its intensity.”

To build that world, we set about clearing and rebuilding, deliberately laying out our facilities and equipment to channel the sustained fight ahead. We put our hooches as close as possible to work areas, including the task force screening facility (which would hold new captures for initial interrogations before we transferred them to internment at Camp Bucca), so that TF 714's leaders could frequently visit and observe, in the process reinforcing our mission and our values.

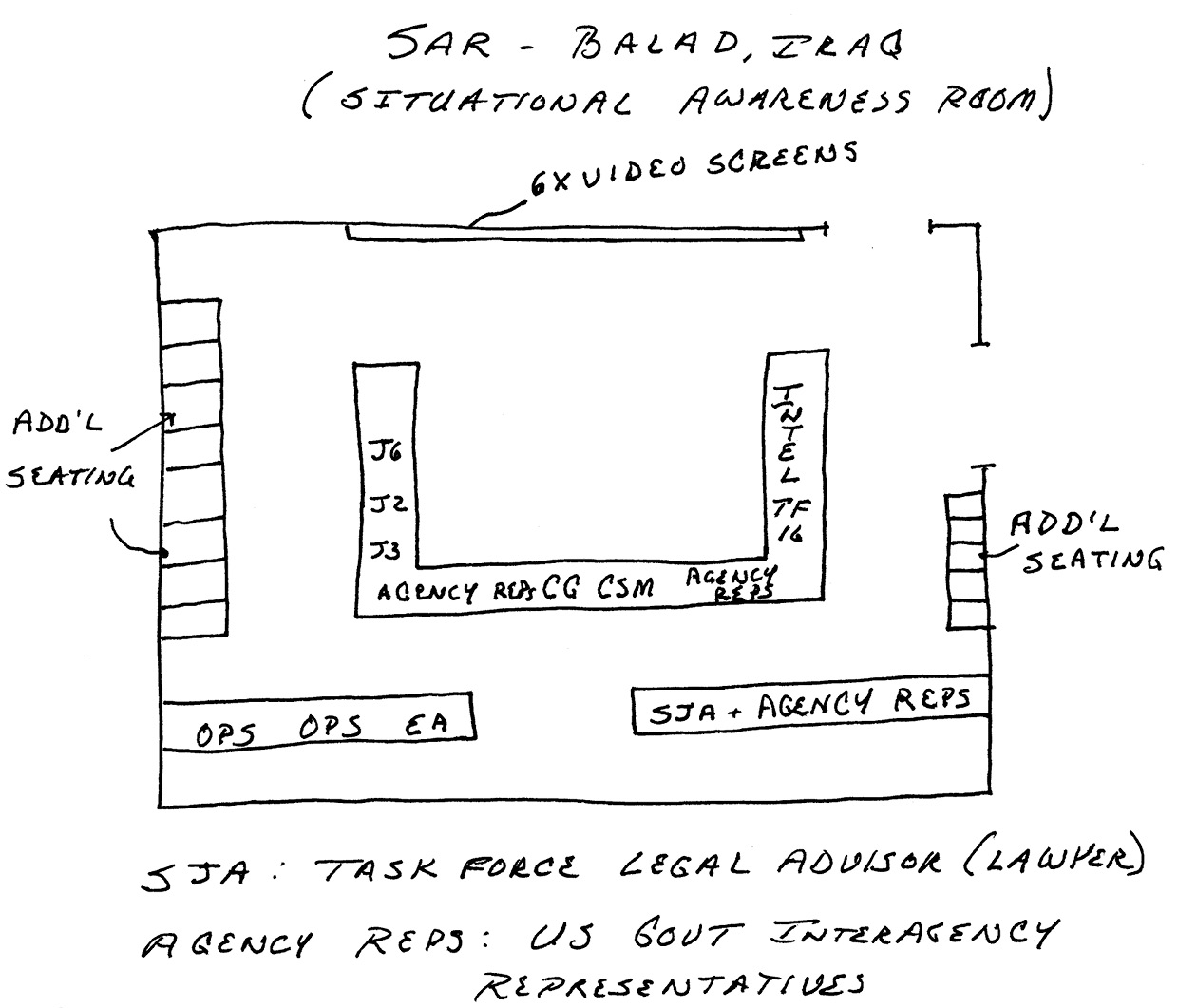

We placed our headquarters and that of the Iraq-focused TF 16 inside one of the three hardened air shelters that sat within the TF 714 footprint. A big concrete dome the size of a circus tent, with beige reinforced walls several feet thick and bowed openings at each end, it resembled a giant caramel-colored turtle shell. Its vaulted interior was ideal: By this time, we were convinced the secretive and compartmentalized traditions of special operations forces, particularly TF 714, would doom us. The hard lessons from the previous monthsâof Big Ben and the unnerving speed of the enemy networkâhad chipped away at this dogma. But we knew to deliberately craft our work spaces to channel interaction, force collaboration, and ease the flow of people and information.

Rather than divide the interior into a honeycomb of offices, we congregated all of TF 16 in the middle of the hangar and, in an unprecedented move, made the whole cavernous interior a top secretâsecure facility: Everything could be discussed on the open floor, so secrecy was no excuse for not cooperating with the rest of the team. Facing a wall of screens displaying a ticker of updates and streaming real-time video of operations, the TF 16 commander and his key staff sat at a rectangular horseshoe table. Behind them were four rows of tables, divided like a theater. Although a few offices lined the perimeter, the sixty or so people who coordinated TF 16's workâintelligence analysts, operations officers, military liaisons, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) operators, airpower controllers, FBI agents, and medical plannersâsat in these rows.