My Story (20 page)

Authors: Elizabeth J. Hauser

The suit was brought by an obscure lawyer, but it was not at all difficult to trace it to the real perpetrators â the public service corporations of Cleveland. In the latter part of June, 1902, the supreme court declared unconstitutional the charter under which Cleveland had been operating for about twelve years, though its legality had never before been questioned. Ten days before our three-cent-fare franchises were to be bid for, the supreme court, upon application of Attorney-General Sheets, enjoined the city of Cleveland from making any public service grants of any kind. Other cities of the State were operating under charters just as “unconstitutional” as Cleveland's, but

not one was enjoined. All other cities were left free to carry on their own affairs. By these rulings of the supreme court our hands were literally tied in our street railway fight and they were kept tied for eleven long months.

During the summer of 1902, a special session of the State legislature, inspired by Senator Hanna, was called to adopt a new municipal code â one which should apply to all cities of the State, and remove from Cleveland the obloquy of “special legislation.”

Though the legislature was importuned and beseeched to give to all the cities of Ohio the Cleveland form of government, known as the federal plan, and thus provide a uniform system in accordance with the constitutional requirement, and at the same time give an excellent plan of municipal government, they refused to do so. Instead, they went to Cincinnati, a city governed by a self-confessed boss who issued his orders by telephone, for the model of that code. The new code provided for board governed cities and is very advantageous to government in the interests of Privilege. Its divided power and no responsibility prevent the people from locating the sources of corruption.

Aimed directly at Cleveland and clearly intended to reduce the mayor to a figure-head, the blow went wide of the mark, as later history will prove.

When my first term as mayor was drawing to its close in the early spring of 1903 and we took an inventory â not of the things we had accomplished â but of the things we had been prevented from doing we found that we had kept the courts pretty fairly busy as the following record of injunctions indicates:

No. 1.

July 22, 1901.â City board of equalization enjoined from increasing the valuation of the Cleveland Electric Railway Company.

No. 2.

Nov. 9, 1901.â Enjoined from entering into contracts for cheaper street lighting.

No. 3.

Nov. 9, 1901.â Enjoined from entering into a contract for cheaper vapor lighting.

No. 4.

April 6, 1902.â Enjoined by common pleas court from carrying out three-cent railroad franchise.

No. 5.

April 7, 1902.â Enjoined from permitting construction of three-cent-fare railroad.

No. 6.

May 11, 1902.â Enjoined from carrying out three-cent franchise by circuit court.

No. 7.

June 30, 1902.â Injunction against three-cent franchise made perpetual.

No. 8.

July 19, 1902.â Enjoined from considering the granting of any franchises. Circuit court.

No. 9.

Aug. 9, 1902.â Temporary injunction by supreme court against considering the granting of any franchises.

No. 10.

Aug. 15, 1902.â Permanent injunction from considering the granting of any franchise.

No. 11 .

Nov. 19, 1902. â Injunction by the supreme court removing the police department from the control of the administration.

No 12.

Dec. 20, 1902.â Enjoined from making any investigation into inequalities in taxation.

No. 13.

March 6, 1903. â Enjoined from making contracts for paving of streets.

These injunctions were the first of the more than fifty which hampered the progress of the people's movement in Cleveland. Injunctions got to be so common during my administration and were made to serve on such a variety of occasions that the practice gave rise to the witticism that “if a man doesn't like the way Tom Johnson wears his hat he goes off and gets out an injunction restraining him from wearing it that way.” Everything we attempted was made the object of misrepresentation, vilification and attack. My part in our various activities and my aggressiveness naturally drew the fiercest wrath and the bitterest abuse to me personally.

MAKING MEN

T

HE

chief value of any social movement lies perhaps in the influence it exerts upon the minds and hearts of the men and women who engage in it. In selecting my cabinet and in making other appointments I looked about for men who would be efficient and when I found one in whom efficiency and a belief in the fundamental principles of democracy were combined I knew that here was the highest type of public officer possible to get. I have stated that I made a good many mistakes in my first appointments, but it must be remembered that innumerable problems faced us. It was like organizing a new government, but more difficult, for we had the old established order with all its imperfections, its false standards and the results of years of wrong-doing to deal with. We really did not have a fair field in spite of the excellent plan of city government which Cleveland had when I was first elected. Men had become contaminated with the spirit of laxity at best, of exploitation at worst, but I soon learned that at bottom men are all right. They would rather be decent than otherwise, and if they have a chance to do really useful work they want to do it. The greatest thing our Cleveland movement did was to make men. It couldn't be enjoined from doing that. The questions we raised not only attracted better men â men who couldn't be inter

ested in politics when it dealt chiefly with spoils,â but it also brought out the very best in men of less exalted ideals.

Many of my appointments gave offense to those within my own party and excited criticism outside. In order to avoid criticism one must follow precedent even when precedent is bad. According to established custom valuable jobs belong by all that is holy in politics to true and tried party workers. They are rewards for the workers. Instead of awarding these jobs as prizes I looked about for men best fitted for specialized public service. The minister of my church, a man of rare spirit and humanitarian impulses, was placed at the head of the charities and corrections, while I chose for city auditor a genial and popular Irishman who had been a liquor dealer. This appointment was offensive to the Puritanical element, while those who insisted on a “business man's government” disapproved of the appointment of the minister. A college professor whose radicalism had resulted in enforced resignation from several colleges was given charge of the city water works with its hundreds of employés, much to the indignation of the Democratic organization. A delegation from the Buckeye Club, an influential Democratic society, called upon me to protest and ended by saying:

“You've got to discharge the professor or we'll fight the administration.”

When they were all through I asked pleasantly:

“Is that your ultimatum, gentlemen?”

They answered with emphasis that it was. I smiled and said:

“Very well; I think I ought to tell you now that I am not going to discharge the professor.”

A brilliant young college graduate just working his way

into practice was made city solicitor, to the amused scorn of some of the wiseacres in the profession. An aggressive Populist, regarded by practically the whole community as a wild-eyed anarchist, was entrusted with the important office of city clerk, a young Republican councilman was selected to take charge of the department of public works and a Republican policeman was raised from the ranks and made chief.

There were plenty of predictions of the disasters sure to follow this unheard-of manner of making appointments, but time justified them so completely that, though I was criticized for many things, even my bitterest enemies didn't charge me with making weak appointments.

As time went on our organization gathered to itself a group of young fellows of a type rarely found in politics â college men with no personal ambitions to serve, students of social problems known to the whole community as disinterested, high-minded, clean-lived individuals. Over and over again the short-sighted majority which cannot recognize a great moral movement when it appears as a political movement, and which knows nothing of the contagion of a great idea attributed the interest and activity of these young fellows to some baneful influence on my part. “Johnson has them hypnotized,” was the usual explanation of their devotion to our common cause.

In selecting its servants Privilege has never cared a straw to which party men belong. It is quite as ready to use those of one political faith as those of another. The people have been slow to profit by the lessons they might have learned from the methods of their exploiters.

Though our work had been hampered by injunctions at every turn and on every possible occasion our political

strength was growing and the personnel of the administration improving in every way. More and more the men connected with us were coming to comprehend the economic questions underlying our agitation.

When the time for another mayoralty election came round we had carried four successive elections, had a Democratic administration, a Democratic council, a majority of the county offices, Democrats in the school council and a Democratic school director in the person of Starr Cadwallader, and for the first time in many years there were Cuyahoga county Democrats in the State legislature. Not injunctions, not court decisions, not acts of the State legislature nor all of these agencies combined had been able to prevent the people from expressing their will through their ballots. I was more eager to succeed myself as mayor than I could possibly have been had our plans been permitted to work out without encountering the opposition of Privilege.

If Big Business was somewhat passive in the campaign of 1901, quite the reverse was true in 1903.

I had by this time incurred the enmity of the tax-escaping public service corporations and big landlords and of the low dive-keepers and gamblers, all of whose privileges had suffered under my administration. The opposition of these interests was augmented by various other groups allied with them in greater or less degree. Many of the church and temperance people opposed me because the town was wide open, while some of the saloons opposed me because the night and Sunday closing laws were too rigidly enforced. The civil service reformers and the party spoilsmen had their grievances, the former because we had not practiced the merit system with regard to city

employés, the latter because we had. The Municipal Association, an organization supposed to be distinctly nonpartisan and above the influences of Privilege, having for its object the consideration and recommendation of candidates to voters, issued an eleventh hour manifesto showing that the city administration had been very lax in enforcing some of the laws most necessary to the well-being of the municipality.

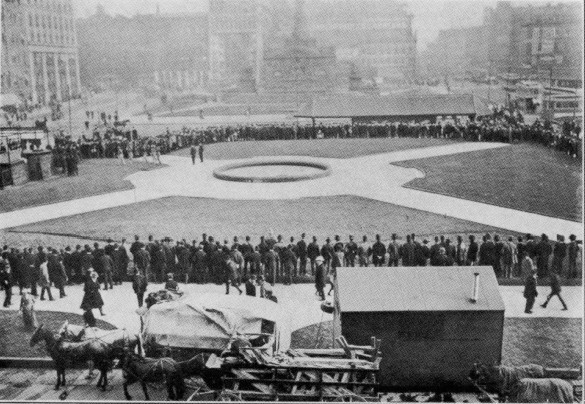

Photo by L. Van Oeyen

Getting ready to pitch the tent in the Public Square, Cleveland, 1902

Let me repeat what I have previously said, that it isn't necessary for Privilege to bribe men with money, with promises, or even with the hope of personal reward, if it can succeed in fooling them. It is this insidious power, this intangible thing which is hard to detect and harder to prove, this indirect influence which is the most dangerous factor in politics to-day.

The Republicans nominated Harvey D. Goulder, a leading lawyer, president of the Chamber of Commerce and a prominent member of the Union Club. I conducted my campaign on the lines of my earlier contests and when Mr. Goulder refused to debate the issues â three-cent fare, municipal ownership of street car lines, and just taxation â with me I conceived the idea of sending a stenographer to his meetings to take verbatim reports of his speeches in order that I might reply to them in my own meetings. The nearest we ever came to a personal meeting was at a political gathering to which we had both been invited. When I arrived Mr. Goulder's haste to get away and his evident ill-nature at being caught in the same room with me caused him to say some unpleasant things about the Jewish club whose guests we were, from which it was inferred that he was accusing someone in the hall of having stolen his overcoat. The coat had simply been

mislaid and was soon found. I felt sorry for Mr. Goulder. I didn't think he really intended to insinuate that the coat had been stolen, but the incident made him a lot of trouble.

In order to curry favor with union labor the Republicans conceived the brilliant idea of nominating for vice mayor Solomon Sontheimer, president of the Central Labor Union. In their speeches some of the Republicans referred to the widely separated interests represented on the ticket by Mr. Goulder and Mr. Sontheimer as a “marriage between capital and labor.” This marriage was doomed to quick divorce, for on election day, when I was elected over Mr. Goulder by about six thousand votes, Charles W. Lapp, the Democratic candidate for vice mayor, won over the Republican, Mr. Sontheimer, by upwards of ten thousand. It had been a bitter campaign and nothing was left undone by the Interests through the Republican organization, aided by a goodly number of Democrats, to beat us. The enemy had an unlimited purse, but how extensively it was used could only be guessed at. In 1901, it will be remembered, I was the only Democrat elected on the general ticket; in 1903 we carried every office on that ticket. Newton D. Baker was elected city solicitor, Henry D. Coffinberry, city treasurer, J. P. Madigan, city auditor, and for directors of public service, Harris R. Cooley, William J. Springborn and Daniel E. Leslie. With few exceptions these officers were already serving the city as appointees of the mayor under the old plan of city government, and we worked together now as we had then like one harmonious family. Most of these officers coöperated as heartily with me as if

they were still subject to appointment and removal by the chief executive.

Mr. Baker, though the youngest of us, was really head of the cabinet and principal adviser to us all. He has been an invaluable public servant and is still city solicitor, having been returned to office in each successive election, even in 1909, when I was defeated with the majority of our ticket. Newton Baker as a lawyer was pitted against the biggest lawyers in the State. No other city solicitor has ever had the same number of cases crowded into his office in the same length of time, nor so large a crop of injunctions to respond to, and in my judgment there isn't another man in the State who could have done the work so well. He ranks with the best, highest-paid, corporation lawyers in ability and has held his public office at a constant personal sacrifice. This low-paid city official has seen every day in the courtroom lawyers getting often five times the fee for bringing a suit that he got for defending it. He did for the people for love what other lawyers did for the corporations for money.

Mr. Cooley, who had been at the head of the city's charitable and correctional institutions from the very beginning of my administration, continued in this department, the duties of the new public service board being divided upon lines which assigned to him this field for which he was so admirably adapted. If service of a higher order on humanitarian lines has ever been rendered to any municipality than that rendered by Mr. Cooley to Cleveland, I have yet to hear of it. His convictions as to the causes of poverty and crime coincided with my own. Believing as we did that society was responsible for poverty

and that poverty was the cause of much of the crime in the world, we had no enthusiasm for punishing individuals. We were agreed that the root of the evil must be destroyed, and that in the meantime delinquent men, women and children were to be cared for by the society which had wronged them â not as objects of charity, but as fellow-beings who had been deprived of the opportunity to get on in the world. With this broad basis on which to build, the structure of this department of Cleveland's city government has attracted the attention of the whole civilized world. How small the work of philanthropists with their gifts of dollars appears, compared to the work of this man who gave men

hope

â a man who while doing charitable things never lost sight of the fact that

justice

and

not charity

would have to solve the problems with which he was coping.

In the very beginning Mr. Cooley came to me and said, “The immediate problem that is facing me is these men in the workhouse, some three hundred of them. I've been preaching the Golden Rule for many years; now I'm literally challenged to put it into practice. I know very well that we shall be misunderstood, criticized and probably severely opposed if we do to these prisoners as we would be done by.”

“Well, if it's right, go ahead and do it anyhow,” I answered, and that was the beginning of a parole system that pardoned eleven hundred and sixty men and women in the first two years of our administration. To show what an innovation this was it is well to state that in the same length of time the previous administration had pardoned eighty-four. The correctness of the principle on which the parole system is based and the good results of

its practice are now so generally accepted that it could not again encounter the opposition it met when Mr. Cooley instituted it in Cleveland. The newspapers and the churches â those two mighty makers of public opinion â were against it, yet it was successful from the very start.