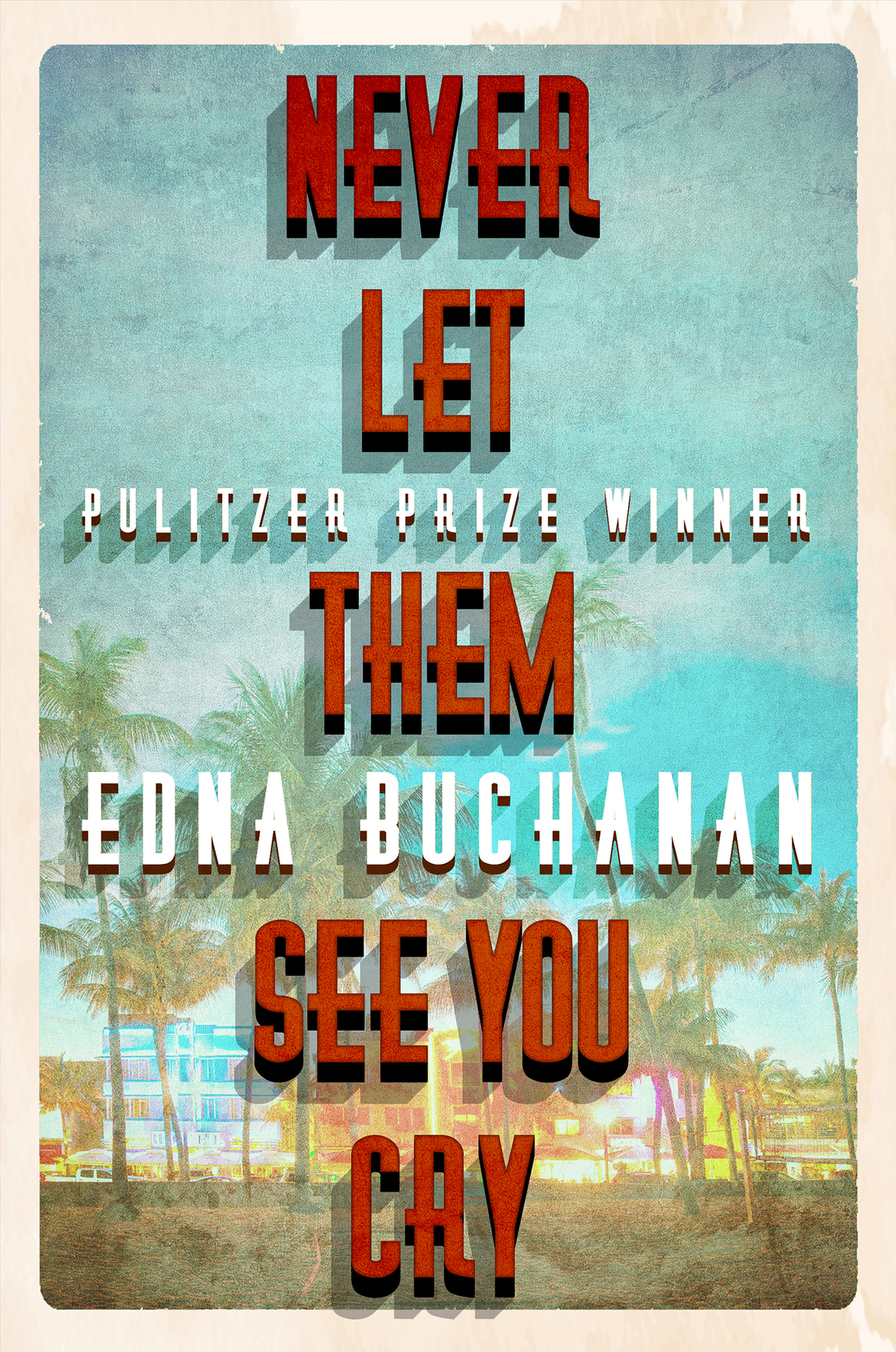

Never Let Them See You Cry

Read Never Let Them See You Cry Online

Authors: Edna Buchanan

Tags: #"BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY/Editors, Journalists, Publishers"

Diversion Books

A Division of Diversion Publishing Corp.

443 Park Avenue South, Suite 1004

New York, NY 10016

www.DiversionBooks.com

Copyright © 1992 by Edna Buchanan

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever.

For more information, email

[email protected]

First Diversion Books edition April 2014

ISBN:

978-1-626812-49-9

Non-Fiction

Carr: Five Years of Rape and Murder

For Quinn and Callie Cagney, and every little girl with big dreams.

Introduction

PART ONE: The Job

1. Putting it in the Newspaper

2. Never Too Young, Never Too Old

3. Love Kills

4. The Twilight Zone

5. Better than Real Life

SIDEBAR: Romance

PART TWO: The City

6. Home, Sweet Home

7. Miami, Old and New

8. Christmas in Miami

9. Best Freinds

SIDEBAR: Duck

PART THREE: The Heroes

10. Fire!

11. Water

12. Street Cops

13. Shot Cops

14. Heroes

SIDEBAR: No Hero

PART FOUR: The Storeis

15. Lorri

16. Lawyers and Judges

17. Mrs. Z

18. Amy

19. Courage

20. A New Chapter

Acknowledgments

About the Author

I had never planned a crime before. I usually arrive after, or during, the action.

Speed and surprise would be the most important elements: Strike swiftly, give witnesses no time to react. Don't seek approval from the people in chargeâask bureaucrats for permission to do anything out of the ordinary and they either say no or launch meetings to consider the question until long past your deadline.

On a leave of absence from

The Miami Herald

to write two books, I had begun to teach a crime-reporting class at Florida International University. At first I was unenthusiastic about teaching. An accidental journalist who had never studied the subject or attended college, my only qualifications were a 1986 Pulitzer Prize, a book called

The Corpse Had a Familiar Face

, published in 1987 and now in use at some journalism schools, and thousands of stories on Miami's police beat. But the offer to teach was one I could not refuse. Journalism had been very good to me, and pay-back time had arrived.

The class took only one night a weekâno problem, that would leave ample time to write my books.

Wrong.

I became hooked on teaching. The term was exciting, the students terrific. We dialogued with experts from the police beat and took a field trip to the county morgue. We posed with the chalk outline of a corpse, surrounded by police crime-scene tape, as Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer Brian Smith shot our class picture.

And I plotted a perfect crime.

No guns, I decided. It was unlikely that any of my eager students would come to class armed, but this was Miami, a city like no other, unpredictable and stranger than fiction.

Ann and D.P. Hughes, the friends recruited to be the perpetrators in this piece of street theater, were uneasy. “I don't want to have to hurt anybody,” D.P. muttered. The tough and savvy chief of operations at the Broward County Medical Examiner's Office, Daniel P. Hughes is also a lawyer and a certified police officer. Ann is his wife. Should you fall grievously ill or injured and spot her sweet face at your bedside, you are in serious trouble. In her soft and soothing southern accent she will talk you, or your next of kin, right out of your vital components. At the very least, she wants your eyes, skin and bones. Your heart, liver, lungs and kidneys would be ideal. Arranging the harvest of human organs and tissues is her job, for the University of Miami and Jackson Memorial Hospital. A woman who smiles freely and laughs often, Ann is dead serious about her work. She is as dedicated to tracking down the right parts for people who need them as D.P. is to investigating how and why some stranger died.

While we conspired, I pointed out to my uneasy friends that these college seniors were not aspiring cops or Marines but would-be journalists: At moments of high excitement they take notes, not action. But I promised to shout “Nobody move! Stay in your seats,” the moment D.P. burst through the classroom door. “Don't worry,” I insisted. “It will all happen so fast, they won't know what went down. They'll freeze in their seats.”

Wrong again.

Midway through my lecture on good cops-bad cops, Ann made her entrance as planned, through a door behind me. She frantically scanned the students' faces. “Where is my son? Isn't this the journalism class? You've got to help me. There's been a terrible accident, I have to find my son and take him home.”

She was good. Very good. Tearfully, she tugged at my arm, skillfully maneuvering me around, drawing me back toward the door she had entered. Remember, this is a woman who can talk you out of your vital organs. She was so convincing that even I, the architect of the scheme, was suckered in.

I missed my cue.

D.P. burst through another door, snatched my black leather handbag off the desk and took off running. I never saw him. By the time I turned around, he was out the door, two students in hot pursuit Scuffling sounds made me spin back toward Ann. She too had fledâor tried to. Before she could escape, a petite woman student had seized her belt from behind and was now scaling her back like a Sherpa ascending Mt Everest.

Outside the classroom, D.P. reached for the police badge tucked in his belt. His pursuers momentarily fell back. Miamians, they assumed he was drawing a firearm. The rest of the class surged forward, a human tidal wave scattering furniture in its wake.

Finally I remembered my lines.

“Freeze! Nobody move!” I flung my arm at the wall clock. “You're on deadline. You have fifteen minutes. Write what just happened. Give me a lead, quotes and descriptions, height, weight, clothing.”

Thirty-four astonished young men and women froze in disbelief. Nervous, adrenaline-charged laughter rippled through the room. Several students stared accusingly. They had been had. A burly young man, big as a linebacker, was too shaken to grasp a pencil.

The lesson, of course, was the fallacy of eyewitness identification, so beloved by juries, so consistently inaccurate.

The written accounts, from these alert young observers who saw everything under excellent conditions, were widely diver-gent.

Ann is lanky and fashion-model tall, with shoulder-length dark hair. She wore a green print jumpsuit. One earnest would-be reporter described her as a “petite blonde in a mini-skirt.” D.P.'s height estimates ranged from five feet six inches to six feet two inches. Ann's attire was described as a leopard print, D.P.'s as a dark, “FBI-style” ensemble. Neither was correct.

An excellent lesson. Hopefully they will never forget it when encountering eyewitnesses. The experience was revealing. Two of the three students quick and courageous enough to chase the “criminals” were young women. That one of them put it together fast enough to pursue Ann without hesitation astonished me.

The students' reactions demonstrated how violence and crime have changed people since I first began to cover the police beat two decades ago. We react faster and more aggressively. Perhaps that is why television shows on unsolved mysteries and wanted fugitives are so successful. Viewers jam telephone lines calling in tips, turning in their neighbors. We are all fed up with crimes unsolved and missing children never found.

Crime fighting has become a participatory sport.

A few years ago who would even have envisioned a journalism course specializing in crime reporting? Teaching it remains a fond memory, but I will never do it again. I became too fond of my students to replace them with a room full of strangers. My time is better spent reporting and writing.

The term ended, and before saying good-bye, I made them promise to always observe the journalist's three most important rules:

1. Never trust an editor.

2. Never trust an editor.

3. Never trust an editor.

It was difficult to part with them, tougher than covering rapes, riots, plane crashes and more than five thousand violent deaths. So was embarking on a book tour. A lifetime of cops and crooks was nothing compared to

Oprah, Late Night with David Letterman

, and the

Today

show and trudging down long, cold airport concourses in strange cities with sunless climates. The temperature was twelve the night 1 arrived in Boston, with the wind-chill factor twenty to thirty degrees below zero, the coldest night in Boston in one hundred years. “Where's your coat?” cried the publicist who met me at the airport.

Leaving Miami is like leaving a lover at the height of the romance. The city is an enigma that constantly unfolds, and I don't want to miss a moment. But authors, it was explained to me, must introduce their books to the world. I asked my friend, mystery novelist Charles Willeford, what I should know about the book tour. He did not hesitate: “Never miss a chance to take a piss.”

Men

, I thought, sighing impatiently, disappointed and frowning at Charles.

Why must they always be crude?

Soon after, departing a Pittsburgh radio show during the book tour, I told the publicist who had me in tow that I in-tended to stop at the rest room before leaving. “No way,” she said firmly, pushing me aboard an elevator. “We're behind schedule already.”

Charlie was right.

Another radio and one TV show later, my keeper consulted her schedule. “You can go now,” she announced, “but make it fast.” Authors on a book tour are like prisoners of war, with better accommodations.

The hotels are not bad, but I hate airplanes.

After too many years of covering crashes, I am always sure that the man in the cockpit is under the influence of cocaine, about to suffer a major coronary, or simply suicidal. Snowstorms made my flight to Minneapolis five hours late. The waiting publicist, impatient at my delayed arrival, drove us at ninety miles an hour at one

A.M

. in her tiny car over icy roads through snow and sleet No food seemed to be available at that hour in Minneapolis, and although the bellman said he turned on the heat in my room, it never worked. I piled all my clothes on the bed and huddled miserably beneath them. Exhausted, but too cold to sleep, I thought I was freezing to death. My only goal was to survive long enough to escape.

The publicist arrived at dawn. Her first question was, “How can you

live

in Miami?” How? My toothpaste was frozen, it was too cold to take a shower, and she wondered how I could live in Miami? I prayed that the approaching blizzard would stall long enough for me to fly out on schedule late that after-noon. For the first time in my life, I was eager to board an airplane.

I scrambled out of her car at the airport so hastily that the sleeve of my borrowed coat dragged through a slushy black puddle at the curb.

There was something unreal about the Twin Cities airport. While waiting, I realized what it was. The only language heard was English, and all the strangers seemed to be light-skinned, fair-hairedâand even polite.

After a one-hour delay, we soared into blinding snow. In front of me, a little boy about eight years old became violently airsick, screaming, retching and vomiting all the way to Washington. Nobody could be that sick and live. I feared he would not survive the flight. Was there a doctor aboard, I wondered, or would we be forced into an emergency landing to save his life? As we filed off the plane, in Washington at last, my knees trembling, I heard the boy, who appeared near death minutes earlier. “When can we get something to eat?” he eagerly asked his parents. He was starved, he announced. Children are so resilient. It took me three days to recover.

I was scheduled to appear on a radio show twenty minutes later. The station was thirty minutes away, under good driving conditions. A stranger hustled me to his car, careened like a madman through ice and snow and delivered me just before air time, my knees still shaky.

Not until the wee hours did I finally arrive at my hotel, longing for sleep, haggard and weather-beaten, my makeup long lost in some far-off city, my belongings crumpled and disorganized at the bottom of a battered garment bag. A message was waiting: A newspaper photographer would arrive to shoot my picture at dawn.

There were many other unforgettable moments, such as the routine takeoff from New York's Kennedy Airport, quickly followed by the emergency landing at LaGuardia, ten miles away.

Little wonder that the sight of soft pink and gray mists rising off the great swamp as we swept in over the Everglades to land in Miami brought tears to my eyes. Little wonder that the usual cacophony of noisy, rapid-fire talk in half a dozen exotic dialects was music to my frostbitten ears. Little wonder that I was delighted to come home to the police beat, covering life and death on the steamy streets of the city I love.

On the job a few days later I encountered a perfect eyewitness to murder. Smart, talkative and tough, he was accustomed to violence. Trouble was, he was only three years old.

As I canvassed a tough Miami neighborhood, piecing together the story of a brutal murder, I knocked on a strange door. Michael peeked out from behind his mother's skirt. He wore little red shorts and a

Marathon Man

T-shirt. He had never met the dead tourist, a millionaire who summered in a Montreal mansion and wintered in Nassau. Major heart surgery three months earlier had won the man a new lease on life.

The lease was canceled in Miami.

The millionaire had come from Canada for repairs to his yacht. Lost en route to the boat show, one of Miami's fine winter events, he stopped his rented car to seek directions.

Of all the strangers on all the streets in all the city, he chose a twenty-year-old with a gun, a rap sheet and no conscience.

The tourist stopped at the curb and rolled down his window. The younger man seized the opportunity, wrenched open the car door, piled into the front seat, hit the tourist in the face and drew his gun. “Drive,” he said.

The stunned Canadian obeyed. His unwanted passenger took his money and his gold Rolex wristwatch, then shot him in the chest The gunman grabbed the wheel, steered the car down an alley, shot the wounded man four more times, shoved him out and drove away.

Michael, who had been playing in his backyard, watched all this through a chain-link fence. A young Miami policewoman arrived. He watched her, on her knees, urgently questioning the dying man. Michael appeared perplexed, but suddenly, during the victim's final, terrible moments, he understood. “Mama,” he cried, tugging at her skirt. He pointed at the Canadian. “That's Toby!”

She calmly continued to remove her newly washed laundry from the clothesline. “No, baby, Toby got killed last week.”

Toby had lived and died at the crack house a door away. The man who shot him also drove off. Michael's confusion was understandable. The three-year-old had just witnessed his second murder in two weeks.

Soon after, I arrived, seeking witnesses. Michael was shy until he recognized the face on my wristwatch. “Charlie the Tuna!” he cried. His eyelashes were long and curly, his smile a winner. We had a pleasant chat.

The killer cruised the neighborhood, displaying the blood-spattered rental car to friends, until police caught him. He had pawned the dead man's $15,000 gold Rolex for $95 and had tried without success to spend his Canadian currency.