Neverland (9 page)

Authors: Douglas Clegg

Sumter popped the disgusting meat into his mouth and swallowed, snapping his teeth together so they clicked. “I was getting kinda hungry.”

2I hated fishing.

But what I hated more than fishing were the stories Uncle Ralph would tell in the little dinghy we rented to go out on Rabbit Lake. We launched it into Rabbit Lake, our feet stinging with damp prickers, mud oozing between our toes. Sumter was up to his butt in the water before he leaned into the boat, head and arms first, feet last, sliding in, his teddy bear tucked under his arm.

When he got all settled in, he said to me, “Bernard doesn’t like you.”

“It’s just a stuffed toy,” I said, “and your daddy’s right, you’re too old.”

“If you keep talking like that, I’ll be mad enough to spit tacks, and Bernard’ll eat you before you can blink.”

“That thing ain’t gonna eat nobody, it’s just gonna lose its stuffing.”

“A good bear can tear you limb from limb. I read up on grizzlies, and they’re the meanest. Bernard is part grizzly and part something else.”

“Yeah, huh,” I said, reading the label beneath Bernard’s tail, “part polyurethane.”

“Quiet,” Uncle Ralph whispered, swatting at the air. “You’ll scare the

fish

away.”

fish

away.”

Uncle Ralph was an avid fisherman, wasting no time: The sun was almost completely up, it was nearly six a.m., and his bad jokes could wait no more. “There was this fella who goes to his doctor and the doctor says to him, ‘I’m gonna need a urine sample, a stool sample, and a sperm sample,’ and the guy goes, ‘Well, hey, why’n’t I just give you my underwear?’” Sumter laughed so hard he started hacking, and Uncle Ralph had to slap him on the back. Sumter hawked a loogie out the starboard side, and we watched it splash down and create ripples. A small sunfish came up to nip at it.

“Good one, Daddy, but tell the one about you know the guy who you know gets caught on a you-know-whatever of spit.” Sumter tied a lead weight to the end of his father’s line. Whenever Sumter played with hooks, I stayed as far away from him as possible. He had poked half a dozen hooks through Bernard’s ears, and probably would’ve been just as happy to put them through mine, too. “You know, Daddy, that one about drinking spit. You

know

.”

know

.”

Uncle Ralph had a face like a moose, and his blubbery lips parted in a smile-snarl as he chomped down on a wad of tobacco. “Okay, there’s this guy walks into a bar and he goes, ‘Ain’t got no money, but I’ll do anything for a drink,’ and the bartender goes, ‘Howsabout you take a sip from the spittoon and I’ll give ya a shot of bourbon,’ and the guy goes—”

“Ralph, I think you should stop while you’re ahead.” When my father spoke to his friends or family, his voice was low and authoritative; the stammer he had in his business life never carried over into personal matters. I

used to stand in front of a mirror and try to imitate that deep, unaccented sound, but never could.

used to stand in front of a mirror and try to imitate that deep, unaccented sound, but never could.

Uncle Ralph paused momentarily, but went right on, “Reminds me of this one about this guy . . . ”

We sat in muddy water, me in the very back—because I didn’t want to be up with Sumter and Uncle Ralph—and my father baiting his hook.

I popped the top of a chocolate Yoo-hoo and took a swig. The drink was warm. I leaned back, resting my head against one of the life jackets, and gazed out over the small lake.

Dragonflies whizzed around us as mosquito larvae giggled in aquatic swarms around the edge of our boat. Cattails and reeds swiped at the oars, but we stayed still, and except for the droning sound of Uncle Ralph’s voice and my father’s trying to get him to shut up, we floated like the moss in the Cayman tank, waiting for something to bite. Every now and then Sumter would make a growling noise and pretend it came from his bear, and each time Uncle Ralph looked like he was ready to bite his own boy’s head clean off.

Around eight we broke open the breakfast basket that Julianne had packed the previous afternoon: cold fried-egg sandwiches; cold blackened bacon; thick slices of ham, each with a generous lacing of fat around its edges; a thermos of coffee; and apple juice in bottles shaped like apples. After we’d devoured these, Uncle Ralph said, “Why’n’t you boys go exploring? We can row you over to the island and you can play for a while.” You could see through Uncle Ralph like a pair of binoculars: Sumter had been making too much noise out in the boat, and his father wanted to ditch him so he could catch some fish. Uncle Ralph was a glutton for catfish, and all morning he’d mutter under his breath whenever Sumter began shouting—things like “Land Ho!” or “Thar she blows!” Uncle Ralph didn’t remember that he kept up his own steady stream of vocal noise by telling his off-color jokes. If anyone had scared fish off, he had.

THE ISLAND we jumped off at was barely an acre in size. I waved good-bye to my father and my uncle, but Sumter was already cursing his luck.

“Dang it all, I sliced my toe open.” He plopped to the yellow summer grass, squatting in the mud, turning his foot over so he could view the damage. Blood had bubbled up onto his muddy foot. He plucked a hook out of it, tossing it onto the ground. He wiped his blood-muddy toe onto Bernard’s shaggy stomach. “Sorry, Bernard.”

“Dang it all, I sliced my toe open.” He plopped to the yellow summer grass, squatting in the mud, turning his foot over so he could view the damage. Blood had bubbled up onto his muddy foot. He plucked a hook out of it, tossing it onto the ground. He wiped his blood-muddy toe onto Bernard’s shaggy stomach. “Sorry, Bernard.”

“If you leave it here, somebody else’ll step on it,” I scolded, picking up the fishhook after him.

“Good,” he replied. “Maybe it’ll hook into you and get inside your greasy grimy gopher guts because you squealed.”

“I did not.” I brushed the fishhook off and caught it into the edge of my short-sleeved shirt, carefully twisting it through the cotton to dull the sharp point.

“I lied to my folks, but before supper the Weenie grabbed me and she went and slapped me on the fanny with that abomination of hers that she calls a brush. She said we were doing naughty things in the shack. What exactly did she mean, Beauregard Burton Jackson? What kinds of

lies

did you make up to get me in deep doo-doo? You tell her we were fornicating or somethin’?”

lies

did you make up to get me in deep doo-doo? You tell her we were fornicating or somethin’?”

My face felt hot and red. The heat of the day was sneaking up on us slowly. “I didn’t say

nothing

.”

nothing

.”

“Oh,

huh,

you didn’t, you’d do anything to save your own skin. I bet she made you bawl out loud and you told her. That witch. Well,” he said, calming, “I forgive you, Beau, because I know you knew not what you did.”

huh,

you didn’t, you’d do anything to save your own skin. I bet she made you bawl out loud and you told her. That witch. Well,” he said, calming, “I forgive you, Beau, because I know you knew not what you did.”

“You’re a blasphemer, Sumter.”

“And I’m a rambling wreck from Georgia Tech and a helluva engineer!” He trumpeted, his fists up to his lips. He had mood swings the way Uncle Ralph had cans of beer: one after the other, no matter the time of day. He stopped singing, swatted his hands out like a referee calling foul, and said, “Beau, I think we got company.” He pointed toward a crowded thicket of dried grass. He put a finger up to his lips. “Bernard,” he whispered, “you stay here.”

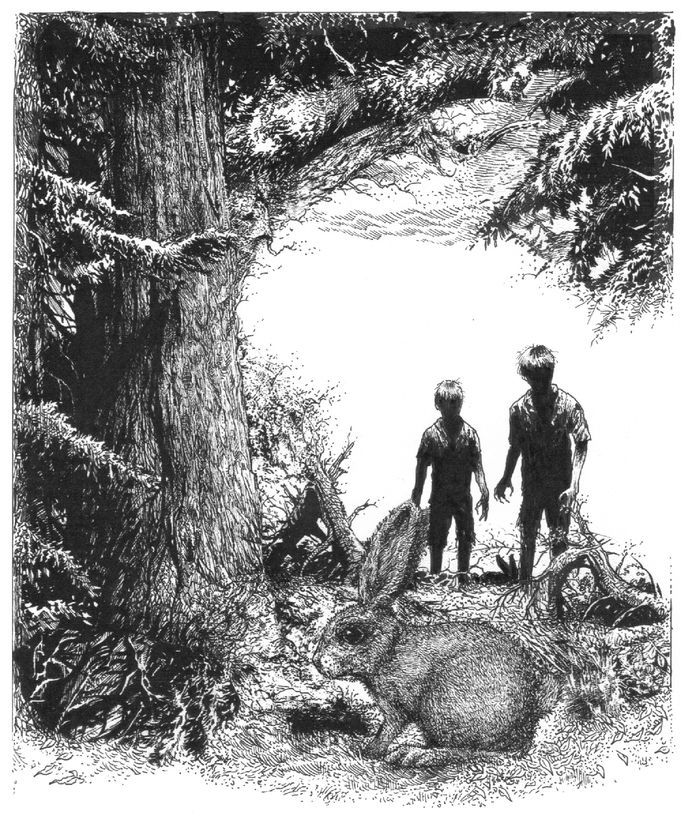

Something moved, there in the sprawl of dried-up grass and prickers.

Two long, white, fluffy ears perked up, and a pink nose sniffed at us.

RABBIT Lake was so named because of the bunnies who occupied the small island we stood upon. These rabbits were here, not because they were natives of Gull Island, but because, over the years, when people vacationed on the peninsula around about Easter-time, the grown-ups would dump their children’s pets out on that mound in hopes that either the animal would drown trying to get back to shore or live out its natural days there.

It must’ve satisfied a sense of what heaven was, for parents could row out with their kiddies and Mr. Flop-ears, let the bunny go, tell the kiddies how happy the bunny would be—much happier than in some crate down in the rec room eating kibble and being bored—and then row leisurely back. The myth would develop of Mr. Flop-ears, who would never die in their imaginations, but live on at the island on Rabbit Lake. The truth was that the bunnies did live on there, multiplying like, well, bunnies, but the small island in the lake became a stockade for the locals, the poor population of the island, the Gullah descendants, too, to whom the soft bunny meat was something of a delicacy. Sumter told me that he thought bunny meat tasted like chicken, “because every weird thing you eat is supposed to taste like chicken.”

It must’ve satisfied a sense of what heaven was, for parents could row out with their kiddies and Mr. Flop-ears, let the bunny go, tell the kiddies how happy the bunny would be—much happier than in some crate down in the rec room eating kibble and being bored—and then row leisurely back. The myth would develop of Mr. Flop-ears, who would never die in their imaginations, but live on at the island on Rabbit Lake. The truth was that the bunnies did live on there, multiplying like, well, bunnies, but the small island in the lake became a stockade for the locals, the poor population of the island, the Gullah descendants, too, to whom the soft bunny meat was something of a delicacy. Sumter told me that he thought bunny meat tasted like chicken, “because every weird thing you eat is supposed to taste like chicken.”

He poked me in the ribs as I came up beside him, tiptoeing even in the mud and grass. “They’re made up of pure innocence,” he whispered. The bunny was small and its soft, white fur was matted with burs and dried mud. Its nose twitched, and it rose up on its hind legs to inspect us before darting back into the high grass. “Pure innocence, the way babies are. Nobody’s told them the way it is yet. Nobody’s told that bunny that it’s gonna be somebody’s supper. It’s living in bliss, Beau, pure bliss ’cause it don’t know what’s coming.”

Because it seemed an intensely private moment—and therefore embarrassing—I didn’t glance directly at my cousin, though I could feel his breath near my ear. But I knew he was crying, maybe not much, maybe just a few tears rolling from his eyes, but I knew he was crying. I pretended not to notice. I saw peripherally that his face was crumpling like rotten fruit. I thought he whispered something, but maybe he didn’t, but it was something that passed between the two of us like a whisper, what was on his mind. “My Daddy wishes I wasn’t ever born.”

We spotted other bunnies in the next two hours, and we even tossed pebbles at some of them. Sumter did not come back to his usual obnoxious self; he was distracted. Finally, as if answering a question in his own head, he turned to me and said, “Give me that hook.”

“Huh?”

He pointed to my arm: the hook he’d cut himself with. I plucked it from my sleeve reluctantly and handed it to him.

He stuck it against his thumb.

I winced, watching.

“Give me your left hand.”

“Uh-uh.”

“We’re gonna take a blood oath.”

“What for?”

“Because of Neverland. You and me, Beau, we’re gonna be joined with blood so you never tell a living soul what you’re gonna find there.”

“I thought you weren’t gonna let me in again.”

“I changed my mind. And you can’t tell nobody ever again about what’s there.”

“Not

much

there.”

much

there.”

“If I told you something.”

“Like what?”

“Like the Slinky attacking the Weenie. Neverland

made

it attack her. Neverland wanted to

kill

her. Like the horseshoe crab—it was a trick, but lotsa tricks happen in there. Like the skull of Lucy, my one true god, which speaks of what will come. And the Gullahs know about Neverland, Beau, they

know,

and they keep out, because of the god I found, and I am the priest of that god. Those dead slaves, they didn’t just

die,

they

consecrated

that ground. But it’s a god that don’t just sit on its ass, cousin. It’s a god of action, of retribution, it’s a god of living bliss and destruction. It’s the god of eternal hunger.” His face was perfectly calm as he said this, and he didn’t seem to move at all, but in the next second I felt the prick of the fishhook, like a needle of ice, thrust into my thumb, and he was holding our thumbs together, kneading the blood as it dripped out in shiny red pearls.

We are jars of blood.

I heard his heart beating in my thumb; I tasted something like the rusty metal of the hook in the back of my throat.

made

it attack her. Neverland wanted to

kill

her. Like the horseshoe crab—it was a trick, but lotsa tricks happen in there. Like the skull of Lucy, my one true god, which speaks of what will come. And the Gullahs know about Neverland, Beau, they

know,

and they keep out, because of the god I found, and I am the priest of that god. Those dead slaves, they didn’t just

die,

they

consecrated

that ground. But it’s a god that don’t just sit on its ass, cousin. It’s a god of action, of retribution, it’s a god of living bliss and destruction. It’s the god of eternal hunger.” His face was perfectly calm as he said this, and he didn’t seem to move at all, but in the next second I felt the prick of the fishhook, like a needle of ice, thrust into my thumb, and he was holding our thumbs together, kneading the blood as it dripped out in shiny red pearls.

We are jars of blood.

I heard his heart beating in my thumb; I tasted something like the rusty metal of the hook in the back of my throat.

“Swear,” he said, “

swear

.”

swear

.”

“No.” I tried to draw back, but our thumbs were glued together. I had to breathe through my mouth because for some reason my nose didn’t seem to work right. I wanted to be back home, or back in the boat. My whole head felt warm, and I felt Grammy’s silver brush stroking through my crewcut.

Flesh is our prison.

I felt imprisoned then, wanting to get out of my body, which felt hot all over, which would not let me run away.

Flesh is our prison.

I felt imprisoned then, wanting to get out of my body, which felt hot all over, which would not let me run away.

“Swear you won’t ever tell, swear in blood.”

“No.”

Grammy Weenie said flesh is our prison

.

.

“Swear.”

Spirit and flesh constantly at war.

“No.”

Angel and Devil

.

.

“By your blood. Say it. Say it.”

Something was pressing into me—not his hand clutching mine, trying to draw my thumb closer to the hook poised for jabbing—but something in my blood, like the tingling feeling I got whenever my circulation failed to kick in, the need of my bones and flesh to move, but my blood went from hot to freezing, icing around my veins, under my skin.

I shut my eyes to will this feeling away.

It was like the strokes of Grammy Weenie’s brush, down through my scalp, creating some kind of electric field around me. Like that, but not, because whatever feeling this was, it was breaking down that field, it was invading my pores, it was turning me to rigid stone, a large block of ice.

“By my blood,” I said and the pins-and-needles feeling crept across the backs of my legs.

“I swear.”

“I swear,” and my breath was frozen in the air.

“I will keep secret.”

“I will keep secret.” My jaws ached, my elbows creaked when I tried to bend them.

Other books

Inside Out by Barry Eisler

Infinity Beach by Jack McDevitt

KARTER by Hildreth, Scott, Hildreth, SD

And the Sea Is Never Full by Elie Wiesel

Duke of Deception by Geoffrey Wolff

Blockade Billy by Stephen King

Summer at the Star and Sixpence by Holly Hepburn

The Siren's Song by Jennifer Bray-Weber

El pájaro pintado by Jerzy Kosinski

Midnight Kiss by Evanick, Marcia