Neverland (5 page)

Authors: Douglas Clegg

The house behind us was nearly invisible from the stand of trees that guarded the shack. The trees were wiry and thin but clumped together, like fingers along the rim of Neverland. There was something like an irresistible smell emanating from the place, or like a high-pitched whistle that only

Sumter and I could hear. I wanted to go inside that place at that moment more than anything in the world.

Sumter and I could hear. I wanted to go inside that place at that moment more than anything in the world.

There was a lock on the door, too, but when Sumter took me up the threshold, he unlocked it with a key.

“How’d you get that?” I pointed to the key.

“Nobody

gave

me it. I took it. You want something, Beau, you just

take

it. If I waited for folks to

give

me things, well, where would I be?” From the way he said this, I knew it was something his daddy had said.

gave

me it. I took it. You want something, Beau, you just

take

it. If I waited for folks to

give

me things, well, where would I be?” From the way he said this, I knew it was something his daddy had said.

“Welcome,” he said, flinging the door wide, “to Neverland. If you tell anybody about this, Beauregard Jackson, I am warning you, it’s gonna be the end.”

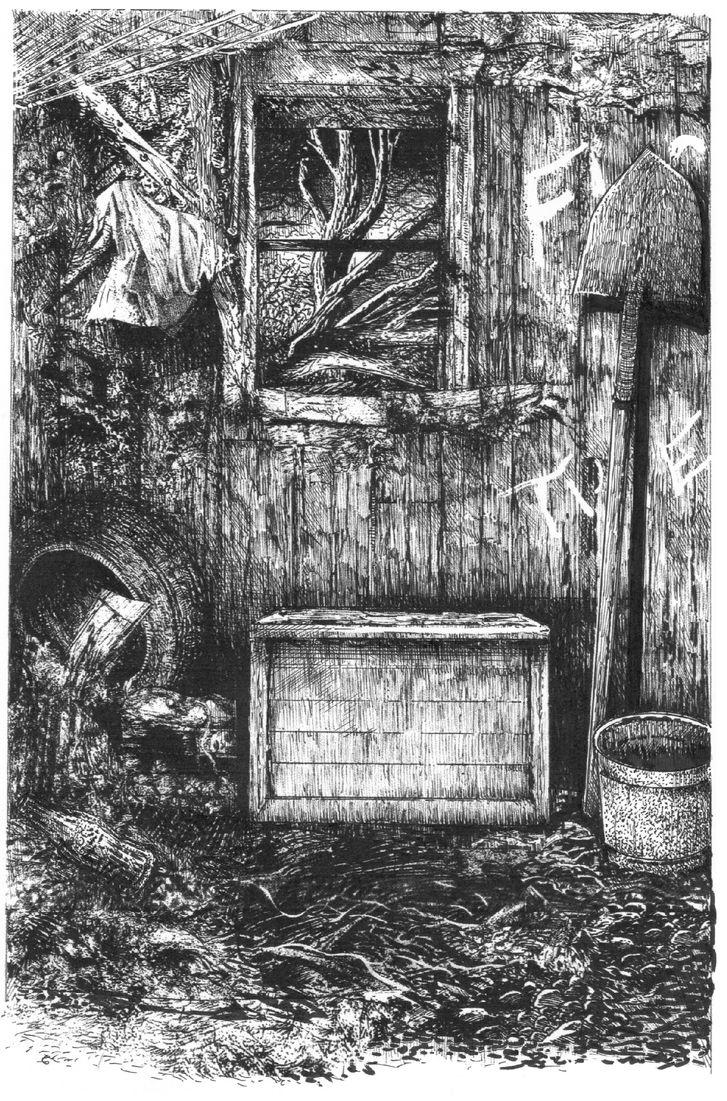

The door, as it opened, scraped across moldy earth and broken clay pots. I got a whiff of something like old socks and detergent and dead sea creatures. For a single moment my curiosity was replaced by dread and I did not want to venture inside.

But I went with my cousin because we were both boys, and boys will always go where they know they shouldn’t.

On the back of the door was spray-painted this warning:

fuck

Fluorescent orange spray paint, curved into curlicues and raggedly connected at the tail end of the

k

. I knew then that no grown-up had been in here in a while, because this one word above all others marked the territory of taboos. This was the road sign.

k

. I knew then that no grown-up had been in here in a while, because this one word above all others marked the territory of taboos. This was the road sign.

I felt as if I were about to enter the Holy of Holies. I crossed myself as a form of protection. The dirt beneath my toes was cold and crumbly.

I peered through the doorway and glanced back at my cousin.

Sumter grinned. His teeth were hopelessly crooked and canine, and his overbite made it seem like he was about to take a chunk out of his lower lip.

“Wait’ll you see what I got in here. Watch out, watch out—” He pointed to bits of broken green glass from Coke bottles that had once been stacked near the door. “Jinx on a Coke, I just saved your life, cuz, so you owe me. I’m always saving your life, ain’t I?”

I couldn’t stop coughing on my first visit within those hallowed walls. You could see the dust hanging in the air—you could practically cut off a hunk of it and bite down.

“Smells like the shower at the YMCA at home,” I said, pushing my way through the gray light, tiptoeing between the thick chips of glass the way I’d seen Indians do it in a Disney movie.

The two windows on the side walls had a skin of dust and grime, and surrounded by trees as the shack was, it gave the effect of being in some dark, underground tunnel. I watched dark spiders run madly under the sills as I tried to wipe away at the glass. I spread layers of dust upon dust. My fingers painted dirt circles without ever cleaning a way to the daylight.

Sumter pointed out a stack of dirty magazines: old

Playboys

, women’s lingerie catalogues, and—his pride and joy—a cutout in the form of a pair of glasses, but these were a woman’s breasts. He picked up the cutout and draped them across the bridge of his nose. “I

see

you, Beauregard Jackson, I

see

you.”

Playboys

, women’s lingerie catalogues, and—his pride and joy—a cutout in the form of a pair of glasses, but these were a woman’s breasts. He picked up the cutout and draped them across the bridge of his nose. “I

see

you, Beauregard Jackson, I

see

you.”

Despite the fact that the

Playboys

had the most female nakedness on display, Sumter’s prize dirty pictures had been culled from the pages of

National Geographic

: endless clippings of topless African women with their lips extended, with a dozen metal rings around their necks, a look in their eyes as if they were not even aware of their nudity. Sumter waved a page in front of me; he pressed the page up to his face.

Playboys

had the most female nakedness on display, Sumter’s prize dirty pictures had been culled from the pages of

National Geographic

: endless clippings of topless African women with their lips extended, with a dozen metal rings around their necks, a look in their eyes as if they were not even aware of their nudity. Sumter waved a page in front of me; he pressed the page up to his face.

“You’re gross,” I said.

Ignoring me, he smooched with the photograph before tossing it down onto the rest of the clippings.

“Hey,” he said to no one. He glanced about, kicking up some dirt around his magazine collection. Then he knelt down and scratched around in the debris. He squinted, sniffing the air. “Something’s changed.”

I looked around. Three old tires leaned against a rusted-out wheelbarrow in my path. Brown-red flowerpots—some cracked, some whole, some

in the process of breaking down into bits of earth and clay—defined a path between the jumble of hacksaw, a manual lawn mower, and miscellaneous souvenirs of yard work.

in the process of breaking down into bits of earth and clay—defined a path between the jumble of hacksaw, a manual lawn mower, and miscellaneous souvenirs of yard work.

“Someone’s been in here.” He rose and began wading across the floor.

“Who’d be in

here

?”

here

?”

“The witch. The Weenie. She’s jealous ’cause I got the key.”

“She wheel in here on her own or’d somebody help her?” I pumped sarcasm into every word.

“I know she did,” he said, clenching his fists tight, closing his eyes as if it hurt to admit this. “She’s so

mad

, she’s so

jealous

, she’s so

jealous

! Why does she

hate

me so much?” He stomped one foot on the ground, and when he did this I thought I felt the ground shaking, but it was only the rattling of paint cans as he kicked one of them. He punched one fist into the other—it looked like it hurt—and when he opened his eyes they were full of tears. His face was red like one of Grammy Weenie’s neck boils. He wiped at his eyes.

mad

, she’s so

jealous

, she’s so

jealous

! Why does she

hate

me so much?” He stomped one foot on the ground, and when he did this I thought I felt the ground shaking, but it was only the rattling of paint cans as he kicked one of them. He punched one fist into the other—it looked like it hurt—and when he opened his eyes they were full of tears. His face was red like one of Grammy Weenie’s neck boils. He wiped at his eyes.

Sumter never scared me when he acted like this. In fact, he only terrified me at his quietest, because it meant he was scheming. But when he went into one of his tantrums, he seemed pathetic and silly, and I always had to suppress the urge to laugh out loud. “Where’s this god thing?” I asked impatiently.

He calmed down a bit, and when he spoke again it was as if nothing had happened. His eyes were dry, his hair only slightly ruffled from the exertion. He wiped the palms of his hands across his shirt. “All the way to the back,” he directed me. He returned to the door, closing it.

With the door shut, Neverland was twilight dark, even though I knew perfectly well it wasn’t even eleven in the morning. Colder, too, and somehow larger, longer—its very geometry having changed with the closing off of its only exit. Sumter went around me, complaining that I was too slow, but my fears of things like black widow spiders and coral snakes—even though I was never sure if they inhabited Gull Island at all—kept me moving carefully amidst the debris.

Sumter bounded over all of it, and when he got to the back corner of the shack, he dragged a plank off the top of a crate. It had pictures of peaches on the outside of it. He lifted the crate up a few inches off the ground and carried it over to where I had stopped walking.

“You keep god in a crate?” I snorted.

I peered into the shadows of the wooden box and thought I saw something move. I was almost frightened, but Sumter was always such a liar and sneak that I knew there wasn’t any god in there. The thing in the crate was in the light. For a second I knew what it was and said, “That ain’t god, that’s a horseshoe crab. How long you been keeping it in here?”

“Three weeks so far.” He was grinning at me like I was about to get a good joke, only I didn’t know it.

“Three weeks! It would be dead by now.”

“Believe what you want, I don’t care.” This was the first time I’d ever heard him express this viewpoint. Normally he begged to be believed, threatened to be believed, threw tantrums until you believed his lies. “If something

is

, it don’t matter if you believe it or not, ’cause it

is

what it

is

anyway.”

is

, it don’t matter if you believe it or not, ’cause it

is

what it

is

anyway.”

“Well, that

ain’t

what it

ain’t

. It’d be dead.”

ain’t

what it

ain’t

. It’d be dead.”

He brought the crab out of the crate and set it down in the dust. It didn’t move, and I figured it must really just be dead. It smelled like it was dead. I prodded it with my toe, and maybe it moved a little, but I figured it was just ’cause I’d touched it. I picked the crab up and shook it, and its innards rattled. Sumter grabbed it from me like I’d offended him and he set it gently back in the crate.

He said, “I got something else, too.”

He reached into the crate, and I was reminded of a magician reaching into a top hat. The creature had probably starved for days before it died, landlocked inside this dry shack. I began to realize how cruel all of us children were with our pets, how we were all cruel small gods, killing our animals, our guinea pigs, our hamsters, our chameleons, our frogs, our salamanders. I was getting physically sick. I remembered seeing a dog that

had been flung out of the back of a truck as it drove down a highway, and, upon hitting the road, the dog had been transformed from a living thing into a piece of butcher shop meat, one half of its fur skinned completely off, and my father saying to me, “Don’t look, Beau, nothing we can do for it.” Who thinks of crabs? I’d seen sea gulls carry them up over concrete and drop them down so the birds could feed more easily on them, but somehow this seemed different. This seemed unfair, that my cousin Sumter would trap this thing in a dark crate for his own entertainment.

had been flung out of the back of a truck as it drove down a highway, and, upon hitting the road, the dog had been transformed from a living thing into a piece of butcher shop meat, one half of its fur skinned completely off, and my father saying to me, “Don’t look, Beau, nothing we can do for it.” Who thinks of crabs? I’d seen sea gulls carry them up over concrete and drop them down so the birds could feed more easily on them, but somehow this seemed different. This seemed unfair, that my cousin Sumter would trap this thing in a dark crate for his own entertainment.

Sumter caught my attention, his hands a blur of movement as he leaned back into the crate. He had extracted something small and yellow and round from the crate.

A very small human skull, one that seemed too tiny to be real. I thought he’d bought it at a magic or joke shop: It was too perfectly deformed, too finely crushed along where the left ear would’ve been.

As if reading my thoughts, he said, “It

is

real.”

is

real.”

“If it’s real, where’s the rest of it?”

“I left it where I found it. This was all I needed. See, she got murdered. Right here.” He grasped the skull like it was a bowling ball, his thumb and forefinger thrust in the eye sockets. “And this is all that’s left of her.”

“Her?”

“Yeah, her name was Lucy and she was in love with this man, and she was going to run off with him, only he didn’t love her. So they met right here, at midnight, and when he kissed her, and she shut her eyes, he placed his fingers around her neck and strangled her. Her eyes popped open in terror and the killer says to her, ‘You will never leave this place. Ever.’”

Sumter had a way with the spur-of-the-moment story, and I’ve got to admit I was taken in for about a minute as he spun this melodrama, but then I knew, like all of Sumter’s stories, this was something he just made up. He had a half-smile that was the tip-off: He enjoyed the company of gullible people.

“If she got strangled, how come it’s smashed in?” I pointed to the left side of the skull, which had large chunks missing.

He gave it up. “Okay, okay, wise-ass. My daddy says there’s this big old grave where these dead slaves were buried right around here, and I guess when they dug out this shack, this,” he practically shoved the skull in my face, “must’ve just been in the dirt. Found this, too.” Again he reached into the crate, and brought out what at first seemed to be a thick twig with several prongs at the end. It was a small animal paw. “Like that story, ‘The Monkey’s Paw.’ Only I don’t think it’s a monkey or anything. Maybe the missing link.” He dragged the edge of the paw along my arm and it tickled. The skin was dried right onto the bone. “Maybe it was some little dog’s. Like someone cut off this dog’s foot. Yeah, they cut it off and hung it up to dry. You see any three-legged dogs, you know we got its foot.”

“I bet you dug those things up. I bet you stole them or something. I bet you weren’t supposed to.”

Now he looked perturbed—he’d been found out. He tossed the skull down on the ground. He lifted three of his fingers up and said, “Peel the banana.” But he peeled it himself, bringing two fingers down around his middle finger, once again flipping the bird, his favorite form of greeting.

“I bet you took those things from somebody and you’re gonna be in trouble for doing it.”

Guilty as he was, he managed to make me feel guiltier for having seen right through his stories. “If you squeal . . . ” Sumter didn’t complete his threat. You may wonder how anyone could feel threatened by someone as apparently sissy as my cousin Sumter, but let me tell you, if you were a kid, you could

smell

what was wrong with him. His stink wasn’t like any other kid’s stink. Grammy Weenie always said you could tell the races just by their smells, and let me tell you, Sumter himself must’ve been from another planet, because he had a smell that was not like anybody else’s, and it came out when he made threats. It was like his juice was switched on electric, and if you touched him, you’d get a blinding shock. I guess I thought then that he was kind of psycho and weird, and I will tell you plainly that I did not like to cross him if I could help it. “If you squeal . . . ” His small fist was raised in the air.

smell

what was wrong with him. His stink wasn’t like any other kid’s stink. Grammy Weenie always said you could tell the races just by their smells, and let me tell you, Sumter himself must’ve been from another planet, because he had a smell that was not like anybody else’s, and it came out when he made threats. It was like his juice was switched on electric, and if you touched him, you’d get a blinding shock. I guess I thought then that he was kind of psycho and weird, and I will tell you plainly that I did not like to cross him if I could help it. “If you squeal . . . ” His small fist was raised in the air.

“I wouldn’t

squeal

.”

squeal

.”

A shower of pebbles hit the window.

“What the—” Sumter motioned for me to duck down. He dropped to the ground and crawled over and around all the rubble. He popped up beneath the window like a jack-in-the-box. “Spies!” he shouted.

“It’s probably just Nonie.”

Other books

Pale Stars in Her Eyes by Annabel Wolfe

Another part of the wood by Beryl Bainbridge

Knot Guilty by Betty Hechtman

Song of Summer by Laura Lee Anderson

Urges: Part Three (The Urges Series Book 3) by Corgan, Sky

Tears of No Return by David Bernstein

Pole Dance by J. A. Hornbuckle

The Hand that Trembles by Eriksson, Kjell

Back to Life by Kristin Billerbeck

Olive of Groves and the Great Slurp of Time by Katrina Nannestad