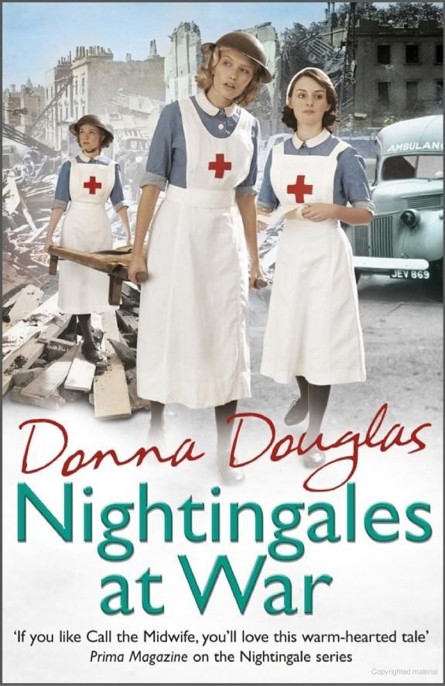

Nightingales at War

Read Nightingales at War Online

Authors: Donna Douglas

Contents

The Nightingale nurses are doing their bit for king and country ...

Dora is the devoted mother of twin babies but, determined to help the war effort, she goes back to work at the Nightingale Hospital.

More used to nights out in the West End, Jennifer and Cissy volunteer in the hope of tending to handsome soldiers.

For shy and troubled Eve, the hospital provides an escape from the pressures of home.

But as the war takes its toll, will the Nightingale Hospital survive the Blitz?

Born and brought up in south London, Donna Douglas now lives in York with her husband. They have a grown-up daughter.

The Nightingale Girls

The Nightingale Sisters

The Nightingale Nurses

Nightingales on Call

A Nightingale Christmas Wish

Donna Douglas

As I say every time, you would not be holding this book in your hands if it wasn’t for the help and support of a lot of people. First, I’d like to thank my agent Caroline Sheldon, and editor Joanna Taylor for bravely stepping into the world of the Nightingales and guiding the project along. I’d also like to thank the whole Random House team, especially Selina Walker and the ever-innovative Andrew Sauerwine and his great sales team.

I’d also like to thank the Archives department of the Royal College of Nursing for their tireless help in tracking down facts, the Imperial War Museum, the Wellcome Library and the Bethnal Green Local History Archives. Not to mention all the brilliant nurses who have shared their stories (most of which are too shocking to include!) and the lovely readers who have taken the Nightingales to their hearts.

Last, but not least, I would like to thank my husband Ken, who has put up with more hysteria than any man should ever have to suffer, and my daughter Harriet, who read each chapter as I wrote it, cheered and booed and cried in all the right places, and whose comments and enthusiasm kept me going. I love you both very much.

To the newlyweds, Harriet and Lewis

ON THE FRIDAY

in May 1940 that Winston Churchill became Prime Minister and the Germans launched a Blitzkrieg of bombs over Holland, Dora Riley went back to the Nightingale Hospital to ask for a job.

It was six years since she had stood before Matron as a student nurse at the Nightingale. But standing in that book-lined office, with its heavy dark furniture and leather-covered chairs, listening to the slow, ponderous ticking of the mantel clock, her heart still raced like a nervous probationer’s as she faced the woman on the other side of the desk.

The world might have changed a great deal over those six years but Kathleen Fox was as serene as ever, sitting tall and graceful in her black uniform, her face framed by an elaborate starched white headdress. Her calm grey gaze fixed on Dora, weighing her up, just as it had on that very first day they’d met.

‘So, Mrs Riley,’ she said. Her soft, well-spoken voice still bore a trace of her Lancashire roots. ‘You wish to come back to us, do you?’

Dora laced her fingers behind her back and stood up a little straighter, as she had been trained to do when speaking to her seniors. Old habits died hard. ‘Yes, Matron.’

‘How long is it since you were a staff nurse here?’

‘Two years, Matron. I passed my State Finals in nineteen thirty-seven, and I left to get married the following spring.’

She kept her eyes fixed on the top of Miss Fox’s headdress as the Nightingale’s Matron considered the notes in front of her. ‘And why do you want to come back, may I ask?’

‘I want to do my bit, Matron. For the war.’

‘Indeed.’ Miss Fox paused. ‘Your husband is serving, I take it?’

‘That’s right, Matron.’ Dora pressed her lips together, not trusting herself to say any more. She had too much pride to show her true feelings. She was a tough East End girl, brought up in the back streets of Bethnal Green, barely a stone’s throw from the hospital itself. Where she came from, it didn’t do to go around weeping and wailing about your troubles. You just buckled down and got on with it, as her mother and grandmother had always taught her.

But inside she was raw from thinking and worrying about Nick. He had been sent off to France in March, and Dora missed him with every fibre of her being.

That was the real reason she had decided to come back to the Nightingale. She had to do something. Not just to help the war effort, but because she knew she would go mad if she stayed at home, fretting and fearing the worst.

‘May I ask why you have applied to us directly, and not to the Civil Nursing Reserve?’ Matron interrupted her thoughts. ‘Surely that is the proper channel for former nurses wishing to offer their services?’

Dora looked at her squarely. She had a feeling Miss Fox already knew the answer to that one.

‘I did, but they won’t have me,’ she said bluntly. ‘They don’t want mothers.’

‘Ah, yes.’ Matron’s mouth curved. ‘You have twin babies, don’t you?’

Dora wasn’t surprised she knew about Walter and Winnie. Even with everything else going on around her, Miss Fox still managed to keep up with all her ‘girls’, past and present. ‘Yes, Matron,’ Dora confirmed.

‘How old are they?’

‘Just a year, Matron.’

‘They’re still so young. I must say, I’m surprised you want to leave them and come back to nursing.’

Dora said nothing. She could already tell from Miss Fox’s expression that she was going to be turned down again, and braced herself for another rejection.

‘I do admire you for putting yourself forward,’ Miss Fox said finally. ‘But the Civil Nursing Reserve rules are there for a reason. As you know yourself, nursing is a vocation. The hours are long, the work is very hard, and war or no war, we expect our nurses to dedicate themselves to this hospital. It’s no job for a wife and mother.’

‘I’ll manage,’ Dora insisted. ‘I’ve moved back home so my mum can look after the twins while I’m working. We’ve got it all worked out.’

‘I see. And supposing you’re in the middle of your shift, nursing several patients on the Dangerously Ill List, and you receive word that one of your babies is poorly. What will you do then? You can’t drop everything and go home, and you’ll hardly be able to do your job properly if you’re worrying about your little ones either.’

‘I won’t have to worry, if my mum’s there,’ Dora said stubbornly. ‘She brought up six kids of her own, she’ll know what to do.’

Miss Fox gave her an almost pitying look. ‘I think you may find you feel differently about that when the time comes,’ she said kindly. ‘A mother’s instinct is to look after her own children, not someone else’s.’

‘Yes, well, I ain’t got much choice, thanks to Hitler!’ Dora hadn’t meant to snap, but she was sick and tired of having doors closed in her face when all she was trying to do was help. They’d been exactly the same at the Labour Exchange, looking down their noses at her when she’d gone to volunteer. ‘Believe you me, I’d like nothing better than to be at home with my husband and kids, but old Adolf and his mob have put a stop to that,’ she went on, ignoring Miss Fox’s startled expression. ‘Now I can either sit at home, twiddling my thumbs and going off my head, or I can be here, making myself useful. And the way I see it, Matron, you could do with some help. From what I hear, you’re having to rely on nursing auxiliaries with five minutes’ training. I know it ain’t ideal, but wouldn’t it be better to have someone like me working here? I want to be useful, and I know I can do a good job. I’ll work as hard as I can, I promise. At any rate, surely I’ve got to be more use than a volunteer who doesn’t know a bedpan from a bandage?’

Dora caught Miss Fox’s frozen stare, and realised that yet again she’d gone too far. Why did she always have to let her temper run away with her? Matron would never have her back now, not if this war went on for a hundred years. She would have to join the Women’s Voluntary Service, making tea and mending socks for soldiers.

‘I see you are still as outspoken as ever,’ Miss Fox remarked, her brows lifting.

‘Sorry, Matron.’ Dora lowered her gaze to the rug. It wasn’t Miss Fox’s fault. She was just following the rules, the same as everyone else. But the whole world seemed to be rules, rules, rules these days. Posters plastered on walls, leaflets from the government through the letter box, all telling her what she could buy, what she should eat, where she could go and who she could speak to. Do this, do that, do as you’re told. It was bad enough that they’d taken her husband away from her, without them trying to run her life too. She was sick of the whole lot of them.

She came back to the present when she realised Matron was addressing her.

‘I hope you realise, Nurse Riley, that if you do return to this hospital you will never be able to speak to me like that again,’ she said.

Dora stared at her blankly. She had barely heard what Matron had said, she was too busy trying to take in the fact that she had just been addressed as Nurse. It was a long time since anyone had called her that, and she hadn’t realised how much she missed it. Pride flowed through her, straightening her spine and making her stand even taller.

But still she could hardly trust herself to believe it. ‘Do you mean – I can come back?’ she asked.

‘As you said yourself, we don’t have a great deal of choice,’ Miss Fox admitted frankly. ‘And while I’d argue with you that most of our nursing auxiliaries do know a bedpan from a bandage –’ Dora withered under her stern expression ‘– I can’t deny it would be useful to have more staff nurses on the wards.’

‘Thank you, Matron.’

‘But as I’ve said, you must not expect any special treatment,’ Miss Fox went on. ‘You will be treated as any other staff nurse here, although of course you will not be expected to live in. But you will be expected to follow orders and to put your duties first, is that understood?’

Her voice was still soft, but with that underlying note of steel that Dora remembered well.

‘Yes, Matron. Thank you, Matron. I won’t let you down, I promise.’

‘See that you don’t, Nurse Riley.’

Dora stared at the older woman’s serenely implacable face and thought she detected the slightest twinkle in her grey eyes.

Dora Riley was right about one thing, Kathleen Fox reflected. Everything was changing. She barely recognised the hospital any more. The windows of the elegant Georgian building were scarred with crosses of brown anti-blast tape, and banks of sandbags were stacked deep against its walls, all but obscuring the ground floor.

Most of the wards had been emptied the previous September when war was declared. The convalescent patients were sent home, and those who were too ill were evacuated, along with most of the staff, down to the Nightingale’s sector hospital in Kent.

Eight months on, and with no sign of the bombs and gas attacks they’d all feared, several of the London wards had reopened. But they had lost a great many skilled nurses to the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service. Kathleen didn’t begrudge them going off to serve their country, but it made it very difficult for her to run the hospital. They were having to rely on former nurses like Dora Riley, and an army of girls from the Voluntary Aid Detachment, or VADs as they were known.

Volunteers who didn’t know a bedpan from a bandage

. Kathleen smiled at the description. Dora had a point. They were willing and cheerful enough, but a few Red Cross classes barely prepared them for the rigours of life on a busy hospital ward.

There was a knock on the door and Veronica Hanley the Assistant Matron strode in without waiting for a reply. Kathleen’s heart sank at the sight of her tall, masculine figure. Now there was someone she wouldn’t have minded sending abroad. She was sure Miss Hanley could have terrified the wits out of the Nazis, far more effectively than the British Expeditionary Force.

She fixed a smile on her face. ‘Hello, Miss Hanley. What can I do for you?’

Miss Hanley slapped a piece of paper down on the desk in front of her. ‘The new linen order,’ she pronounced, in her deep booming voice. ‘There are to be no new sheets or pillowcases. The factory that makes them has been given over to war work.’

‘I see.’ Kathleen picked up her pen to sign the form. ‘I daresay we will soon be asking our patients to bring their bedding in with them.’

Miss Hanley shuddered. ‘Perish the thought, Matron! Are you aware that many of our patients come from homes infested with vermin?’

‘I was joking, Miss Hanley.’

‘Oh.’

Kathleen smiled at the puzzled look on the Assistant Matron’s square-jawed face. Miss Hanley had many excellent qualities, but a sense of humour wasn’t one of them.

It was just one of the many differences that separated them. Veronica Hanley was of the old school, Nightingale-trained and a stickler for tradition. She had never been able to hide her distaste for Kathleen Fox, with her inferior training, brisk northern ways and new ideas.

When the war started, Kathleen had offered Miss Hanley the chance to go to Kent as Acting Matron of the sector hospital. She had thought her assistant would jump at the chance, but Veronica Hanley had surprised her by refusing.

‘I would prefer to stay in London, if you don’t mind, Matron?’ she’d said. ‘It doesn’t seem right to desert my post during the Nightingale’s hour of need.’

Kathleen had reluctantly conceded to her request, even though she suspected it had more to do with Miss Hanley’s wanting to keep an eye on her.

As she signed the order, she could sense the Assistant Matron looming over her, poised to speak.

‘Was there something else, Miss Hanley?’ she asked patiently.

‘The decorators telephoned. They won’t be able to start work on Holmes and Peel wards for at least another two weeks.’

‘That’s a nuisance.’ Since the hospital still wasn’t full to capacity, the Trustees had taken the decision to have two of the empty wards on the top floor painted. ‘Perhaps they could decorate them both at the same time, to make things quicker?’

‘Is that wise, Matron?’ Miss Hanley frowned. ‘Surely it would be better to decorate them one at a time, so we always have a spare ward available in case of emergencies—’

‘We will have them decorated together,’ Kathleen cut across her, irritated. Why did her assistant have to argue with her over everything? ‘I very much doubt we’ll be needing them in a hurry,’ she added more calmly. ‘We barely have enough nurses available to staff the wards we do have open.’

‘Speaking of nurses . . .’ Miss Hanley cleared her throat, and Kathleen knew what was coming next. ‘That girl I saw coming out of your office earlier – am I right in thinking she trained here? Let me think. Nurse . . .’ She made a great pretence of searching for the name. ‘Nurse Doyle, wasn’t it?’

Kathleen bent her head so her Assistant Matron wouldn’t see the smile on her face. Poor Miss Hanley would make a very poor fifth columnist, she thought. She lacked the subtlety for subterfuge. Her broad, plain face gave her away every time.

‘That’s right. Except she’s Mrs Riley now.’

‘So she is. And what brought her here, I wonder?’

As if you didn’t know! Kathleen thought. Miss Hanley would have been listening at the door for the past half-hour.

Playing along, Kathleen said, ‘She wants her job back.’

‘Then she should apply to the Civil Nursing Reserve,’ Miss Hanley said promptly.

‘They won’t have her because she has children.’

‘Ah.’

‘Nevertheless, I have taken her on as a staff nurse.’

‘Really, Matron?’ Miss Hanley couldn’t have looked more scandalised if Kathleen had told her Mussolini himself was going to be working at the hospital as a porter. ‘But the hospital rules clearly state that married women with young children—’

‘I fear we may have to disregard our rules a great deal more than that before all this is over. War changes everything, Miss Hanley. And at least Nurse Doyle – I mean, Riley – trained here, which is more than some of our nurses have these days.’

‘Hmm.’ Veronica Hanley’s mouth firmed. From what Kathleen could recall, Miss Hanley had never really approved of Dora anyway. In her opinion nursing, especially at the Nightingale, was strictly for well-brought-up young ladies from respectable families, and not working-class girls like Dora.