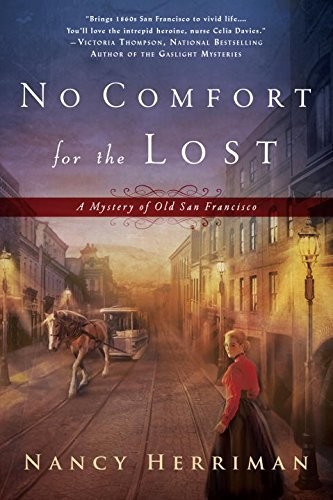

No Comfort for the Lost

Read No Comfort for the Lost Online

Authors: Nancy Herriman

Tags: #Fiction, #Mystery & Detective, #Women Sleuths, #Historical, #Medical

Inside the coffin warehouse, the noise from the street was muted, and curtains drawn over the windows held back the sunshine as if it had no right to enter such a somber place. Nick dragged his hat from his head and closed the front door behind him, the shop bell’s chime disturbing the hush.

He didn’t immediately follow Mrs. Davies as she strode forward between the rows of caskets. He had gone too far, asking about her husband, but it interested him that she’d shed no grief-stricken tears over the fellow. Nick reminded himself that her feelings for her husband, whether he was alive or dead, were irrelevant. After she viewed the body, he’d gather some information from her and put the widow who might not be a widow out of his mind.

She looked over her shoulder with her lovely ice gray eyes—eyes that could pin him to the spot. He couldn’t afford, however, to be fascinated by somebody connected to a murder investigation.

The undertaker, Atkins Massey, hurried from the back room to greet them, the tails of his frock coat flapping against his legs.

“So sorry to be delayed, Detective Greaves!” Massey swiped a pongee silk handkerchief across his mouth, then stuffed the handkerchief into a pocket. He bowed over Mrs. Davies’ fingers, his muttonchop whiskers brushing her skin. “Have you brought a”—his gaze swept over her—“a person who has affection for that sad girl?”

“Mrs. Davies is here to view the body but not to pick out coffins, if that’s the direction your thoughts are heading, Mr. Massey.”

“If the girl is Li Sha,” she said, “I intend to pay for a coffin as well as obtain a space for her at Lone Mountain Cemetery.”

“In that case, we have an excellent selection to choose from. We can even provide the latest in metallic caskets, if you so wish.” Arms spread wide, the undertaker pointed out the caskets on display, their varnish gleaming.

“Mrs. Davies can deal with caskets later, if that proves necessary,” said Nick. “Is the coroner here?”

“Dr. Harris is conducting a postmortem, Detective Greaves.” His attention shifted to Mrs. Davies. “Such a dreadful business. If you require smelling salts, I am at your service.”

She looked offended by the suggestion. “That will not be necessary, Mr. Massey.”

“I’ll be right back, Mrs. Davies,” said Nick.

He headed for the rear ground-floor area where the undertaker tended to those without kin—a large portion of men in this town—or those who’d died of contagious diseases. Everybody else would be looked after by their families in their own homes.

The coroner was at work in the room he borrowed to conduct postmortem examinations. Bowls, jars, and medical instruments glinted on shelves, and the astringent tang of disinfectant drifted on the air. Pairs of scales and glass beakers and a brass microscope stood on a bench against the far wall, the tools of the man’s trade. The law didn’t require that the coroner be a doctor. In fact he could be anybody who ran for the office, so long as the public voted him in. But Harris was a physician and a good one, and the city was lucky to have him.

Harris was bent over the corpse of a balding male whose purplish feet protruded from beneath a cloth. Fortunately, the coroner’s body blocked the view that might have revealed exactly what he was doing. In his lifetime, Nick had seen plenty of torn flesh and spilled guts, but autopsies always raised his gorge.

“Dr. Harris,” he said, drawing the man’s attention from the corpse. A large incision in the man’s torso was hastily covered. They must have examined Meg like this after they’d found her. It was the thought Nick had every time he saw Harris at work. A thought he wished he could strike from his brain.

“Detective Greaves,” the coroner said with a smile. “You must be here about that Chinese girl.”

“I’ve brought someone who might be able to identify her.”

“Good. The inquest is this afternoon, and I’d like to have a name for the paperwork.” Harris dropped his scalpel into a nearby bowl, then rinsed his hands in another. He wiped them across the clean corner of the bloodied apron tied over his clothes. “Brought in as a drowning victim,” he said, noting that Nick was staring at the male corpse. “Second one this week. Looks to be an accident. Considering the state of his liver, I’d say he was drunk as a loon when he fell into the bay.”

Harris strode across the room and past Nick, shutting the door to the sights within. “So who have you brought? The brothel owner?”

“A nurse who runs a medical clinic for poor women. She sometimes treats the Chinese.”

“Ah.” Harris dragged his fingertips through his beard, which was bristling with gray, and chuckled. “Mrs. Davies, is it?”

“I was hoping you’d know her.”

“Know

of

her is more like it.”

“And what do you know?”

“Well, she’s been in San Francisco for only a few years—”

“Three, she told me,” Nick interrupted.

“Sounds right,” said Harris. “Her clinic’s just outside the Barbary, and I gather she served in the Crimea and in an army hospital back east during the war, not sure which one. And I believe she trained at the Female Medical College in Philadelphia, very solid credentials. Lives with a half-Chinese girl—the daughter of a deceased gold miner, I hear, and some sort of relative.” He scratched at his beard. “I’ve also heard that her passion for her female patients has led to plenty of disputes with some of the physicians in town. Personally, I’ve never had the pleasure of meeting Mrs. Davies. Doctors’ wives can be”—he paused, his smile apologetic—“particular in who they invite to social events.”

“Because she’s had disputes with the local physicians, or because she has a half-Chinese relative?”

“Both, I suppose,” he admitted. “And her tendency toward bluntness does her no favors.”

Blunt and stubborn. A perfect description. “Mind if we take a look at the girl now?”

“She’s in the basement. There’s no one else down there at the moment, so you don’t have to worry about Mrs. Davies seeing too much.”

Before Nick could leave, Harris stopped him. “What’s Eagan got to say about this? I’m surprised he’s letting any of his detectives spend time on this case.”

“What my boss doesn’t know won’t hurt him,” answered Nick.

Harris chuckled again, and Nick returned to the main room. Massey had made use of Nick’s absence to show Mrs. Davies his array of funerary trappings—black plumes to decorate the hearse and the horses that drew it, swaths of ebony cloth for draping over caskets or wagons or just about anything, velvet if a person wanted extra luxury. Extravagances meant to awe the living, because they certainly wouldn’t impress the dead.

“Mrs. Davies, please come with me,” said Nick.

“Excuse me, Mr. Massey.” She accompanied Nick to the basement stairs, gripping the railing as she descended. It was cold down here, perfect for slowing decay, and gloomy. Spare caskets were propped against one of the walls, and a floor-to-ceiling curtain blocked off the area where bodies awaiting identification were kept. The smell of death filled every corner, seeped out of every stone. This was no place for a lady, even one with as much grit as Celia Davies.

She paused at the bottom step. “Where to now, Mr. Greaves?”

“Back here.”

He parted the curtain. Daylight coming through a set of windows illuminated the three marble slabs that occupied the space. The girl had been laid upon the center one, a length of dark fabric draped over her body.

Mrs. Davies stepped slowly forward. Nick peeled back the cloth, just enough to reveal the girl’s face with all its bruises, along with the abrasion that traced a pink line across her neck.

“Yes.” She nodded. “That is Li Sha.”

“Thank you.” Nick flicked the fabric back into place too hastily, accidentally revealing the girl’s right arm and the lacerations that had torn the skin.

“Sliced by a bayonet?” Mrs. Davies clapped a hand to her mouth.

He grabbed the cloth and recovered the body. “Let’s get you out of here.”

Nick led her up the stairs and past Massey, who was clutching a bottle of smelling salts. “Mrs. Davies?” He unstoppered the bottle and waved it beneath her nose.

“I am perfectly fine.”

“She’ll select a coffin some other time, Mr. Massey,” said Nick, refusing to release this woman, fragrant with lavender and strong soap, who felt too right pressed against his side. “And tell Dr. Harris the girl’s name is Li Sha.”

• • •

“

I

appreciate your assistance, Mr. Greaves,” Celia said, disregarding the gawkers passing by as she braced a hand against the nearest telegraph pole, her reticule swinging from her wrist. Until the last moment, she had hoped the police were wrong, hoped she would walk into that cold room and see a different unfortunate girl lying dead. But the body on that slab was Li Sha, the even planes of her lovely face unmistakable though puffy and bruised, the swell of her abdomen holding an unfulfilled promise of new life. How Li Sha had looked forward to becoming a mother.

“You must think I am forever dashing out of buildings for one reason or another, Detective,” said Celia.

His mouth twitched with a smile, bringing warmth to his eyes. Though his curt disposition rubbed her raw, she could not deny he was handsome.

“Twice isn’t enough for me to draw a conclusion, Mrs. Davies.” The hat brim took a turn through Mr. Greaves’ fingers, and he squinted against the sunlight. “Would you care to sit down? There’s a decent coffeehouse nearby.”

She was grateful for the suggestion; answering questions in a coffeehouse would be preferable to doing so in the fetid air of the police station.

“I’d enjoy some coffee, yes, Mr. Greaves. And a sandwich, if they offer food. I should try to eat.” Though her hunger had vanished in the coroner’s makeshift morgue. “However, I shall not permit you to pay my bill.”

He tapped his hat upon his head. “Didn’t think you would.”

As promised, the coffeehouse was not far. Given the reception he received from the owner, the detective must be a regular customer. Though she preferred tea, the coffee brewing smelled heavenly as they wended their way between tables. There were only a handful of other customers—all male—and plenty of empty seats, but Mr. Greaves chose a table beside the large front window where they could be readily seen. Protecting her reputation, she presumed.

He held her chair as she took a seat. He made a quick scan of the room before settling across from her, facing the door. He was ever watchful, indeed.

They placed their orders, and his expression became sympathetic. “I’m sorry about the girl, Mrs. Davies. Not the way anybody’s life should come to an end.”

His sentiment did not seem contrived, though Celia expected he’d had to extend similar words to sorrowing families and friends many times before.

“‘Tired he sleeps, and life’s poor play is o’er,’” she said sadly. “Although in this case, it’s a

she

.”

“Is that some sort of quote?” he asked.

“Alexander Pope, Mr. Greaves,” she said. “Poor Li Sha. A difficult life come to a terrible conclusion. I did not, however, anticipate slashing wounds from a bayonet.”

“What makes you think they were bayonet wounds? Harris often reminds me how tough it is to tell what sort of blade has caused a cut on a body.”

She considered his observation. “Perhaps I see them where there are none, Detective. A consequence of months spent in army hospitals.”

“I am familiar with bayonet wounds, too. I volunteered in an Ohio regiment.” Detective Greaves rubbed a spot above his left elbow, then flexed his hand as if testing its ability to function. He noticed the direction of her gaze. “Old war wound.” He dropped his hand to the table. “Saw more killing than anybody should have to witness. We all did.”

“War is never as grand as it reads in the papers, Mr. Greaves.”

“In that we agree, ma’am.”

His steady brown eyes watched her without further comment, and she looked away, out the window at the pedestrians and the traffic. A curly-tailed mongrel snuffled at the gutter, and a sunburned boy called out, “Po-ta-toes,” at the top of his lungs, competing with the shouts of a particularly dirty fellow in a shabby jacket trying to sell old rags and patched boots. Across the way, a black-haired woman in an indigo dress hurried along the pavement, and Celia momentarily thought she looked familiar. But it was a trick of the mind, and she was forced to recall that Li Sha was gone.

“Officer Mullahey called Li Sha a prostitute,” she said, returning her gaze to the detective’s face. The coffeehouse was considerably more quiet than the din outside, the volume of conversation having fallen when they entered. She suspected they were being stared at. “She had been, at one time, although not a common one. Because she was unusually lovely, and could sing and play the Chinese two-stringed fiddle, she worked in a parlor house as a concubine.”

“A parlor house.” Mr. Greaves lifted an eyebrow. “Nicer than the usual cribs.”

“It is a discreet establishment and enjoys, I’ve been told, a higher class of clientele than the stews of China Alley. Rich white men, even.” Men who could indulge their taste for the exotic without dirtying their shoes in the worst parts of the Barbary and the Chinese streets.

“But she still wore face paint,” Mr. Greaves observed.

“Her one vanity.”

“How exactly did you meet her?”

“She was my first Chinese patient. It was last autumn—September, if I am not mistaken—shortly before she stopped working at the parlor house. An abusive customer had injured her, broken a rib, and some of her wounds had festered, though she had attempted to heal them with traditional Chinese medicines. I treated her as best I could and she recovered. But after that assault, she resolved to escape the life she was leading.”

Coffee and a ham sandwich arrived, delivered by the proprietor himself, a robust man with an Eastern European accent who lingered too long at the table, until Mr. Greaves frowned at him. Celia gripped her cup, letting it warm her fingers, and resumed speaking.

“Eventually, Li Sha earned enough from selling the gifts customers had given her to pay her way out of her contract. She was one of the fortunate ones, to be able to do so.” Celia sipped some of the bitter coffee. “After she left the parlor house, she came to me, seeking help. I was more than happy to do all I could. I considered taking her into our house, but I had to make allowances for my cousin Barbara. She can be anxious around people who are not family, and I also have her reputation to protect.”