No Limits (25 page)

Authors: Michael Phelps

In Baltimore the next weekend, the city formally welcomed me home with both a parade, which also honored Katie Hoff, as well as Paralympic athletes and Special Olympians, and then a fireworks show at Fort McHenry, birthplace of “The Star Spangled Banner.”

All of it was amazing. It sometimes seemed surreal, especially because I never set out to be a celebrity. I set out to be the best I could be and then to do something no one else had ever done, and as we zipped from one city to the next, it was never far from my mind that, for sure in my case, celebrity comes with a certain responsibility. I was privileged enough that people wanted to hear me and see me. What was it I could tell them?

The answer, in part, came with the establishment of a foundation we set up immediately after the Games that bears my name with the aim to get kids into swimming and to help teach health

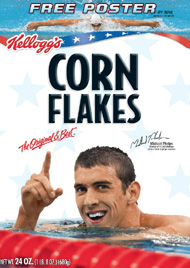

ier lifestyles. I donated the entire $1 million Speedo bonus. Then Speedo and its North American licensee, The Warnaco Group, Inc., announced another $200,000 donation, and Kellogg's, which put my picture on boxes of Frosted Flakes and other products, donated another $250,000. One of the foundation's first initiatives: visits to a number of cities to launch an educational program that helps kids achieve their goals. The program is based on what my mom and Bob, in particular, helped me learn when I was younger: to set goals, take responsibility, and practice discipline.

Maybe we're onto something. By the fall, USA Swimming announced that record numbers of kids were signing up at local clubs. In Mount Laurel, New Jersey, enrollment in the learn-to-swim program doubled; in Chicago, the Lyons Swim Club saw a 28 percent increase in their team size from the beginning of August through the end of September; in Farmington, New Mexico, the Four Corners Aquatic team grew by 40 percent; in Sarasota, Florida, the YMCA Sharks added 135 new members, a 36 percent increase.

Through all the glitz and the glitter after the Games, some of my best memories will always be the quieter moments, especially those I was lucky enough to spend with kids, particularly at Boys & Girls Clubs across the country. In Burbank, California, at the Boys & Girls Club, a seven-year-old named Javier Silva gave me a handmade leather bracelet; he had put eight little gold rings on it. He told me that he had watched me swim a lot at the Olympics and that he was my number-one fan. I told him I would wear it; I was true to my word. A few days later, at the Dunlevy Milbank Community Center in Harlem, I watched a group of about two dozen boys and girls swim laps. Never, I said, let anyone tell you that anything is impossible. “There were people who said no way anyone could win eight medals,” I said. “When people say that, I want to prove them wrong. I was able to prove them wrong this year. And one of the best things about

the most exciting time in my life was looking up and seeing my mom there.”

All over the countryâreally, the worldâpeople have gravitated toward my mom. As many people, maybe more, have come up to say, “We love your mom,” as have said, “Congratulations.” At the close of

Saturday Night Live,

the female cast members kept saying, we love your momâshe's awesome!

She is awesome.

In early October, President Bush welcomed more than five hundred members of the 2008 U.S. Olympic and Paralympic teams to the White House. We gathered on the South Lawn and, as part of his remarks, the president said, “People say, did you ever get to meet Michael Phelps? I said I did. So that was the highlight? I said, not really. Meeting his mother was more of a highlight. She reminded me of my motherâplain-spoken and full of love.”

Everywhere my mom went after the Olympics, people would stop her and say, “Hey, Debbie,” hundreds, maybe thousands, of people she had never before met calling her by her first name as if they were old friends. People wanted just a moment with my momâto say thank you, to say wow, to say what a great family we are. Mom had people tell her that the love she had for me and my sisters, and all of us for her, was something that America needed, that it was evidence of American values at their best. Mom had people stop her at the store and say, “Debbie, outstanding jobâwe are so proud of you and your son.”

Mom also starred in one of the best stories that came out of the 2008 Summer Olympics. Mom likes to shop at a clothing store named Chico's. After she got back from Beijing, she went to her favorite Chico's and, after some parking difficulties, was approached by a security guard in the parking lot. He started talking to her. Then a flash of recognition lit his face.

“Hey,” he said, “I know you. Youâyou're the seven-medal mama.”

Mom didn't miss a beat. She said, “Eight.”

The little boy who would grow to become the greatest gold medalist in Olympic history turns three with a backyard birthday party.

What a future Olympic gold medalist looks like on his first day of kindergarten: Michael boarding the school bus under the watch of big sister Whitney.

Michael at eight with Hilary (left) and Whitney, the sisters in Christmas pajamas, a Phelps family tradition.

Back problems kept Whitney (left) from achieving her Olympic goals, adding incentive for a teenage Michael to carry forward the family dream.

Michael at fifteen warming up before the 200 fly at the 2000 U.S. Trials, the meet that would send him to his first Summer Olympics.

At the 2001 world championships, sixteen-year-old Michael (right) takes gold in the 200 fly; Tom Malchow, Olympic champion only the year before in Sydney, claims silver.

Michael taking off at the Pan Pacific swim championships in 2006 in the 200 backstroke, an event he hasn't tried to race at the Olympicsâyet.

Michael not only wins this 200 fly in Texas in 2001 but, timed in 1:54.92, makes swim history as the youngest world-record holderâfifteen years, nine months.

Not just great theater, but a gesture of genuine solidarity and support at the 2004 Olympic Trials from the one and only Mark Spitz (left), winner of seven gold medals at the 1972 Munich Games.

A beaming Michael just a few minutes after out-touching Ian Crocker by four-hundredths of a second to win gold in the 100 butterfly at the 2004 Athens Olympics.

What could be more all-American? After the 2008 Olympics, Michael appears on special boxes of Kellogg's Corn Flakes and Frosted Flakes.

They're off in the race that rocked the 2007 worlds in Melbourne. Michael, fifth from bottom, is en route to a stunning 1:43.86 in the 200 free, breaking Ian Thorpe's world record by two-tenths of a second.