Read North Yorkshire Folk Tales Online

Authors: Ingrid Barton

North Yorkshire Folk Tales (24 page)

At that time highwaymen were all the rage. There were ballads and chapbooks about them everywhere. Gay’s

The Threepenny Opera

had come out not long before and everyone, including me, fancied himself MacHeath.

Well, thought I, I want to be a gentleman and highwaymen are gentlemen of the road, so why delay further? I betook myself with my pistols to the Cambridge Road and waited for my prey.

Soon a well-dressed man came riding along. I stood forth into his path with my pistols pointed at his breast saying ‘Stand and deliver!’ To my surprise he merely laughed.

‘Well said, my lad. Almost like a highwayman! What’s your name?’

‘Dick Turpin!’ says I.

‘Well, Dick my cully, I’ve heard of you,’ says he, ‘and I fancy you’ve heard of me, for I am Captain Tom King!’

That is how I joined forces with the most famous highwayman of his day. He took a liking to me and we agreed to share our ventures and to lodge together in a secret cave between King’s Oak and Loughton Road. We worked the roads through Epping Forest. Do not think that we were at all ill-housed in a cave, for everything we needed was supplied by my dear Mary, who had been living at this time on the earnings of a little public house I had procured for her when I was a smuggler. She brought us food and drink; many a merry party did we have together.

My acquaintance with Captain Tom did much to improve my manner, for he was a gentleman born and bred. He taught me much, laughing often at my ignorance and country ways. I brooked his correction knowing that it would help me in the future, as indeed it did.

The fickle wheel of fortune turned once more when a foolish man called Morris, inspired with greed for the £100 at which my bounty now stood, came after me. I was forced to shoot him and though it was in self-defence and entirely his own fault, in the eyes of the law I was now a murderer The bounty on my head was raised to £200 and a description of me printed and spread abroad. It was not flattering, but it was near enough to cause me trouble:

About five foot nine inches high, very much marked with the smallpox, his cheeks broad, his face thinner towards the bottom, his visage short, pretty upright and broad about the shoulders.

Tom King was not pleased with me. We quarrelled about Morris, but we went on working together. Then one night he went to Whitechapel to pick up a good horse that I had conned out of a man called Major. The Runners were waiting there, thinking to get both of us and claim the reward. You will hear scrubs bad-mouthing me but I never meant to shoot Tom; I was aiming at the Runners. My horse tossed his head as I shot and the ball went wide and hit Tom instead. He fell like a dead man. I overcame my horror enough to escape but later I heard that poor Tom lingered on for a week before he died. Better than hanging? No, it was no way for a highwayman to go.

After that I had to get out of Essex. The last time I saw my Mary, for she died soon after, she begged me to go north, saying that she had no wish to see me dance on empty air at the gallows. She gave me some money and food and I left my old haunts forever.

This time I set myself up in Lincolnshire at a place called Long Sutton. The fame of Dick Turpin being less well known here, I rented an apartment and dressed as a gentleman, being accepted as such by my neighbours.

You may think that my life would now be peaceful but the truth is that I was soon tired of this quiet life. There were no easy chubs to cheat at cards and no light women to drink with. After a time, some of my old acquaintances came into the county and I fell into my former ways. There were plenty of very fine horses around, not well guarded and so we turned to ‘prigging gallopers’ as my vulgar friends called it.

It was a good trade for I could easily sell the disguised horses in York. I soon gained a great acquaintanceship there where I passed as a wealthy horse trader. I called myself Palmer, after my dear Mary. After a time I decided to remove there, York being a fine city and much more to my taste than Lincolnshire.

One evening, I was riding home with some of my rich friends when my landlord’s cockerel came strutting out in front of us, crowing fit to burst your ears. On a whim, I shot it, occasioning much mirth in my companions as well as praise for my shooting. My landlord was not so happy though and the rogue clapped a fastener on me. I had to appear before the magistrates in Beverley and was remanded on bail. This was my downfall, for I had no ready money on me to pay it.

The magistrate stretched his eyes and said, ‘Mr Palmer, you have the appearance of a gentlemen and so I am amazed that you cannot easily pay your bail. I fear that as you are newly come to the county I must investigate you further for we want no bankrupts here nor wanted men.’

I was transferred to the debtor’s prison in York Castle. Hearing that I was in trouble for money, all my creditors began to dun me. Soon questions began to be asked about the horses I had sold and I was indicted for horse stealing.

One of my prison colleagues suggested that I should get a friend from my past to write a letter of good character for me. ‘This is not London,’ he said, ‘The magistrates here will believe what they read if it be well written.’

I thanked him and wrote to my brother, the only person I knew in the world who might be persuaded to give me a good character, for most of my old acquaintances were either dead, in prison or unable to write. I thought of Captain Tom with regret. Here is what I wrote:

Dear Brother,

I am sorry to acquaint you that I am now under confinement in York Castle for horse stealing. If I could procure an evidence from London to give me a character, that would go a great way towards my being acquitted. I have not been long in this country before being apprehended, so that it would pass off the readier.

For heaven’s sake dear brother do not neglect me. You will know what I mean when I say I am yours,

John Palmer.

Now was fortune determined to ruin me. Retribution waited to dash me to the ground. My dear brother refused to pay the postage owed on my letter and it was returned to the post office. By the veriest chance, a man spotted it and thought he recognised the handwriting. He asked one of the magistrates to be allowed to open it for he thought it was writ by the notorious highwaymen Dick Turpin. His request was granted and so the one man who could recognise my writing, my old teacher Mr Smith, revealed my true identity!

Now all York rejoiced that such a famous figure had been captured in their own city. My trial was short, considering the evidence against me, but the courtroom was filled by the very best sort of people, tender-hearted ladies weeping at my cruel fate and men offering me drink. The court ushers roared themselves hoarse and the judge, putting on the black cap, could scarce make himself heard as he delivered the deadly verdict.

Since being placed in the condemned cell, which is a large room they have here in York Gaol, I have had no peace. So many visitors have come and gone, wringing my hand or begging a remembrance of me. I am determined to be turned off in style; I feel I owe it to Tom to die like a gentleman and it is in my mind to give them all a surprise. I have ordered a new suit and shoes and distributed to my friends what possessions remain to me. I have ordered my last meal and laid out ten shillings for five mourners to follow the hangman’s cart.

The chaplain has been here wearying me with talk of repentance but I have sent him away with a flea in his ear. Life has been good and I regret none of it except perhaps Captain Tom. Let God watch out! I mean to drink with the Devil tomorrow night. Then we’ll raise Hell together!

Farewell!

![]()

Turpin was hanged at Tyburn on the Knavesmire in York on 19 April 1739. A great crowd collected to accompany the cart from the prison. Turpin bowed to them all and continued to greet acquaintances all the way to the gallows. Once there, he leapt easily up the ladder onto the scaffold. He refused a blindfold and stood with the noose around his neck, chatting to the guards and hangmen for half an hour before jumping off without assistance. He was dead in moments.

His body had some adventures of its own. It was first taken to the Blue Boar public house in Castlegate where the landlord put it in his parlour and charged visitors to see it. In the end, Dick’s friends had to steal it to stop people from cutting off parts of it. (Whether for keepsakes or black magic is not clear.)

Even after burial the body did not rest in peace but was dug up several times by bodysnatchers. On one occasion it was found in the garden of a surgeon.

In the end it was buried in quicklime in the churchyard of St George’s church where the grave may still be seen.

HE

P

IRATE

A

RCHBISHOP

Sometimes a person appears in the world with more than usual vitality or charisma around whom folk tales begin to gather like barnacles around an old boat; Mrs Thatcher is an example from our own time.

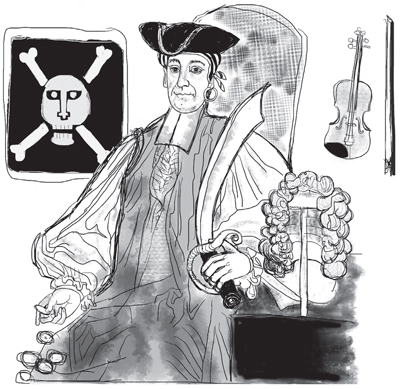

Archbishop Blackburne of York is forgotten now, but in his day his obscure history and his less than virtuous character meant that by his death he had become, quite literally, legendary. Some of what follows may be true, but which bits?

![]()

Over the south door of York Minster there is a series of canopied arches in the centre of which, not too long ago, the statue of a fiddler once stood. It was put there by Archbishop Lancelot Blackburne to celebrate a stolen fiddle.

Lancelot was born in the middle of the seventeenth century and grew up in the wild and wicked times of the Merry Monarch, Charles II. As a second son, he was destined for the Church and was sent to Cambridge to study theology.

Life as a student in those days was – believe it or not – rather more exuberant and violent than it is now. Betting, drinking matches, horseracing, duelling, fighting, rioting and general laddishness were the pleasant pastimes of many of the richer students, despite their all being intended for holy orders. Lancelot took to this delightful life with gusto; he played the fiddle well and was a popular addition to many a raucous party. So enthusiastically did he embrace the riotous life that, before his first term was over, he found himself ‘gated’ (forced to be in by 7 p.m.) for missing church.

Such a restriction was to Lancelot like a red rag to a bull. Already unhappy with the boredom of the university’s teaching he decided that he did not want to stay at Oxford any more. What use was education when there was a world to explore? One afternoon he walked out of his rooms intending to run away to London. He had already exhausted the allowance from his parents and was just considering how he would earn his bread when he passed his tutor’s open door. There on the table was a fine violin. Lancelot’s own fiddle was a poor cheap thing, fit only to play at drunken parties, but this was a different instrument altogether. It seemed to reach out to him begging to be taken. So he took it, hiding it in the voluminous folds of his cloak. It was this superior violin that provided him with his meal ticket every night, as he busked in inns on his journey to the metropolis.

London in those days was many times smaller than it is now, but it was still large and bustling enough to daunt anyone arriving for the first time. Luckily for Lancelot he had been born and bred there, so he already knew many of its ways and secrets. Instead of going home to face the wrath of his father he survived by staying with friends and hanging around on the fringes of the court. There he managed to pick up small (usually shady) jobs from court officials. It was hard to make enough to live on though, and when he nearly died from the cold, he realised that he would have to do something more positive. He had always fancied going to sea, though he did not want to join the Navy, and so he got himself bound as an apprentice on a Newcastle collier,

Fair Sally

.