Notebooks (36 page)

Authors: Leonardo da Vinci,Irma Anne Richter,Thereza Wells

Tags: #History, #Fiction, #General, #European, #Art, #Renaissance, #Leonardo;, #Leonardo, #da Vinci;, #1452-1519, #Individual artists, #Art Monographs, #Drawing By Individual Artists, #Notebooks; sketchbooks; etc, #Individual Artist, #History - Renaissance, #Renaissance art, #Individual Painters - Renaissance, #Drawing & drawings, #Drawing, #Techniques - Drawing, #Individual Artists - General, #Individual artists; art monographs, #Art & Art Instruction, #Techniques

4. PAINTING AND SCULPTURE

Comparison between Painting and Sculpture

Painting requires more thought and skill and is a more marvellous art than sculpture, because the painter’s mind must of necessity enter into nature’s mind in order to act as an interpreter between nature and art; it must be able to expound the causes of the manifestations of her laws, and the way in which the likenesses of objects that surround the eye meet in the pupil of the eye transmitting the true images; it must distinguish among a number of objects of equal size, which will appear greater to the eye; among colours that are the same, which will appear darker and which lighter; among objects all placed at the same height, which will appear higher; among similar objects placed at various distances, why they appear less distinct than others.

Painting requires more thought and skill and is a more marvellous art than sculpture, because the painter’s mind must of necessity enter into nature’s mind in order to act as an interpreter between nature and art; it must be able to expound the causes of the manifestations of her laws, and the way in which the likenesses of objects that surround the eye meet in the pupil of the eye transmitting the true images; it must distinguish among a number of objects of equal size, which will appear greater to the eye; among colours that are the same, which will appear darker and which lighter; among objects all placed at the same height, which will appear higher; among similar objects placed at various distances, why they appear less distinct than others.

The art of painting includes in its domain all visible things, and sculpture with its limitations does not, namely the colours of all things in their varying intensity and the transparency of objects. The sculptor simply shows you the shapes of natural objects without further artifice. The painter can suggest to you various distances by a change in colour produced, by the atmosphere intervening between the object and the eye. He can depict mists through which the shapes of things can only be discerned with difficulty; rain with cloud-capped mountains and valleys showing through; clouds of dust whirling about the combatants who raised them; streams of varying transparency, and fishes at play between the surface of the water and its bottom; and polished pebbles of many colours deposited on the clean sand of the river bed surrounded by green plants seen underneath the water’s surface. He will represent the stars at varying heights above us and innumerable other effects whereto sculpture cannot aspire.

213

213

The sculptor cannot represent transparent or luminous substances.

214

214

How the eye cannot discern the shapes of bodies within their boundaries were it not for shadows and lights; and there are many sciences which would not exist but for the science of shadows and lights—as painting, sculpture, astronomy, a great part of perspective and the like.

It may be shown that the sculptor does not work without the help of shadows and lights, since without these the material carved would remain all of one colour. . . . A level surface illumined by a steady light does not anywhere vary in the clearness and obscurity of its natural colour; and this sameness of the colour indicates the uniform smoothness of the surface. It would follow therefore that if the material carved were not clothed by shadows and lights, which are produced by the prominences of the muscles and the hollows interposed, the sculptor would not be able uninterrupted to watch the progress of his work, as he must do, else what he fashions during the day would look almost as though it had been made in the darkness of the night.

Of painting

Painting, however, by means of shadows and lights presents upon level surfaces, shapes with hollowed and raised portions in diverse aspects, separated from each other at various distances.

215

215

The sculptor may claim that

basso relievo

is a kind of painting; this may be conceded as far as drawing is concerned because relief partakes of perspective. But as regards the shadows and lights it errs both as sculpture and as painting because the shadows of the

basso relievo

in the foreshortened parts, for instance, have not the depth of the corresponding shadows in painting or sculpture in the round. But this art is a mixture of painting and sculpture.

216

basso relievo

is a kind of painting; this may be conceded as far as drawing is concerned because relief partakes of perspective. But as regards the shadows and lights it errs both as sculpture and as painting because the shadows of the

basso relievo

in the foreshortened parts, for instance, have not the depth of the corresponding shadows in painting or sculpture in the round. But this art is a mixture of painting and sculpture.

216

That sculpture is less intellectual than painting

and lacks many of its inherent qualities

and lacks many of its inherent qualities

As I practise the art of sculpture as well as that of painting, and am doing both in the same degree, it seems to me that without being suspected of unfairness I may venture to give an opinion as to which of the two is of greater skill and of greater difficulty and perfection.

In the first place, a statue is dependent on certain lights, namely those from above, while a picture carries its own light and shade with it everywhere. Light and shade are essential to sculpture. In this respect, the sculptor is helped by the nature of the relief, which produces them of its own accord; while the painter has to create them by his art in places where nature would normally do so.

The sculptor cannot differentiate between the various natural colours of objects; the painter does not fail to do so in every particular. The lines of perspective of sculptors do not seem in any way true; those of painters may appear to extend a hundred miles beyond the work itself. The effects of aerial perspective are outside the scope of sculptors’ work; they can neither represent transparent bodies nor luminous bodies nor reflections, nor shining bodies such as mirrors and like things of glittering surface, nor mists, nor dull weather, nor an infinite number of things which I forbear to mention lest they be wearisome.

The one advantage which sculpture has is that of offering greater resistance to time. . . .

Painting is more beautiful, more imaginative and richer in resource, while sculpture is more enduring, but excels in nothing else.

Sculpture reveals what it is with little effort; painting seems a thing miraculous, making things intangible appear tangible, presenting in relief things which are flat, in distance things near at hand.

In fact, painting is adorned with infinite possibilities which sculpture cannot command.

217

III. ARCHITECTURAL PLANNING217

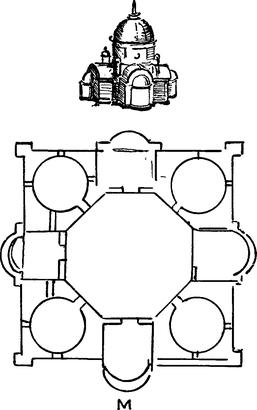

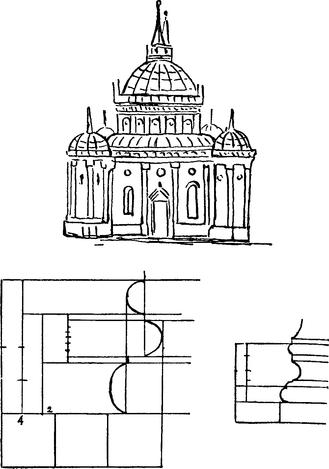

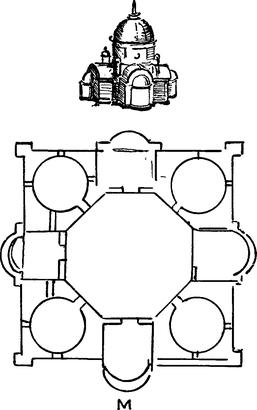

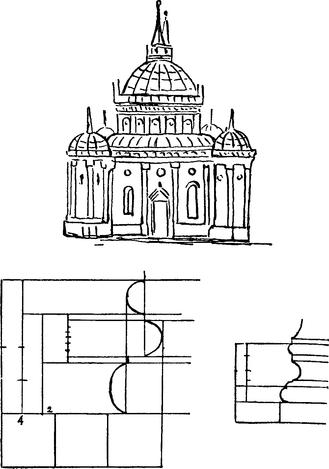

Leonardo’s manuscripts contain a number of architectural designs for domed cathedrals built on a central plan where structural problems are dealt with theoretically and from an artistic point of view. He also designed forts, villas, castles, pavilions, and stables for his patrons. His advice was sought regarding the completion of the cathedrals of Milan and Pavia.

He was interested in theoretical questions of practical importance

—

in problems such as what form of a church would best answer the requirements of acoustics

.

He wrote on arches and beams and the pressure which they sustain; on the origin and progress of cracks in walls and how to avoid them

.

—

in problems such as what form of a church would best answer the requirements of acoustics

.

He wrote on arches and beams and the pressure which they sustain; on the origin and progress of cracks in walls and how to avoid them

.

His ideas on town

-

planning and on arrangement of houses and gardens combine art with technical knowledge

,

and provide for plenty of light

,

air

,

and open space

,

noise

-

proof rooms

,

two

-

level highways

,

and issues of sanitation

.

-

planning and on arrangement of houses and gardens combine art with technical knowledge

,

and provide for plenty of light

,

air

,

and open space

,

noise

-

proof rooms

,

two

-

level highways

,

and issues of sanitation

.

The diagrams reproduced from one of his notebooks indicate the rules as given by Vitruvius and by Leon Battista Alberti for the proportions of the Attic base of a column.

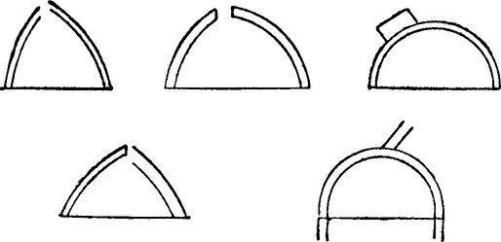

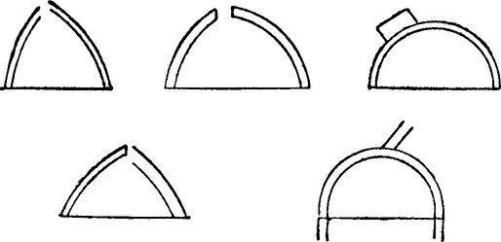

What is an arch?

An arch is nothing else than a strength caused by two weaknesses; for the arch in buildings is made up of two segments of a circle, and each of these segments being in itself very weak desires to fall, and as one withstands the downfall of the other the two weaknesses are converted into a single strength.

Of the nature of the weight in arches

When once the arch has been set up it remains in a state of equilibrium, for the one side pushes the other as much as the other pushes it; but if one of the segments of the circle weighs more than the other the stability is ended and destroyed, because the greater weight will subdue the less.

218

218

Here it is shown how the arches made in the side of the octagon thrust the piers of the angles outwards as is shown by the lines

hc

and

td

which thrust out the pier

m

; that is they tend to force it away from the centre of such an octagon.

219

hc

and

td

which thrust out the pier

m

; that is they tend to force it away from the centre of such an octagon.

219

An experiment to show that a weight placed on an arch does not discharge itself entirely on its columns; on the contrary the greater the weight placed on the arches, the less the arch transmits the weight to the columns. The experiment is the following: Let a man be placed on a steelyard in the middle of the shaft of a well, then let him spread out his hands and feet between the walls of the well, and you will see him weigh much less on the steelyard. Give him a weight on the shoulders, you will see by experiment that the greater the weight you give him the greater effort he will make in spreading his arms and legs and in pressing against the wall, and the less weight will be thrown on the steelyard.

220

220

Other books

Back Track by Jason Dean

Frolic of His Own by William Gaddis

I Will Plant You a Lilac Tree by Laura Hillman

If the Dead Rise Not by Philip Kerr

Sweetheart Deal by Linda Joffe Hull

UnSouled by Neal Shusterman

Buckhorn Beginnings by Lori Foster

The Feathery by Bill Flynn

For Love of Mother-Not by Alan Dean Foster

Huckleberry Hill by Jennifer Beckstrand