Notebooks (54 page)

Authors: Leonardo da Vinci,Irma Anne Richter,Thereza Wells

Tags: #History, #Fiction, #General, #European, #Art, #Renaissance, #Leonardo;, #Leonardo, #da Vinci;, #1452-1519, #Individual artists, #Art Monographs, #Drawing By Individual Artists, #Notebooks; sketchbooks; etc, #Individual Artist, #History - Renaissance, #Renaissance art, #Individual Painters - Renaissance, #Drawing & drawings, #Drawing, #Techniques - Drawing, #Individual Artists - General, #Individual artists; art monographs, #Art & Art Instruction, #Techniques

Buy handkerchiefs and towels, hats and shoes, four pair of hose, a jerkin of chamois and skin to make new ones. The lathe of Alessandro. Sell what you cannot take with you. Get from Jean de Paris* the method of colouring al secco, and how to prepare tinted paper, double folded, and his box of colours. Learn to work flesh colours in tempera, learn to dissolve gum shellac. . . .

82

82

The following note which is not in Leonardo’s hand may refer to a part of the same exploit. He was to report on the state of the fortifications of Florence after the death of Savonarola in 1498.

Memorandum for Master Leonardo to secure quickly informations on the state of Florence, videlicet, in what condition the reverend father called friar Girolamo had kept the fortresses. Item the manning and armament of each command, and in what way they are equipped, and whether they are the same now.

83

83

The exploit of the count of Ligny came to nothing. On 14 December 1499 Leonardo sent his savings amounting to 600 florins to be deposited at Santa Maria Nuova in Florence. He then left Milan for Venice in the company of Fra Luca Pacioli. They stopped at Mantua on their way and were welcomed by the marchioness Isabella d’Esté, who sat for Leonardo for the drawing of her profile which is now at the Louvre. Though her sympathies were with her defeated brother-in-law, Ludovico, she was anxious to conciliate the victor and save her husband’s little state and she invited the count of Ligny, who was connected to her family, to Mantua.

In the first days of February 1500 Ludovico crossed the Alps and re-entered Milan. His friends rejoiced, but the struggle was not yet over. Leonardo was awaiting the outcome in Venice.

III. SECOND FLORENTINE PERIOD (1500 - 1506)On 13 March 1500 Lorenzo da Pavia, il Gusnasco, the lutenist, wrote from Venice to Isabella d’Este that he had seen Leonardo’s portrait drawing of her and had found it so good, it could not be improved.

On the piazza of Santi Giovanni e Paolo Leonardo could see the bronze equestrian statue of Bartolommeo Colleoni which was modelled by his master Verrocchio after he had left Florence, and cast in bronze by Alessandro Leopardi in 1493.

The Venetian Senate availed itself of Leonardo’s presence to procure his advice on the defences at Friuli and on the river Isonzo. The Turks, who had defeated the Venetian fleet at Lepanto in August 1499, were now threatening the frontier.

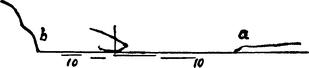

In the following draft Leonardo advocates a scheme for inundating the countryside. On the same sheet is a sketch of road and river communications with the inscription:

In the following draft Leonardo advocates a scheme for inundating the countryside. On the same sheet is a sketch of road and river communications with the inscription:

Bridge of Gorizia Wippach [Vippacco]

My most illustrious Lords—As I have carefully examined the conditions of the river Isonzo, and have been given to understand by the country folk that whatever route on the mainland the Turks may take in order to approach this part of Italy they must finally arrive at this river, I have therefore formed the opinion that even though it may not be possible to make such defences upon this river as would not ultimately be ruined and destroyed by its floods. . . .

84

84

On a later date he recalls the work on a sluice at Friuli made at this time.

And let the sluice be made movable like the one I devised in Friuli, where when the floodgate was open the water which passed through hollowed out the bottom.

85

85

At RomeAt old Tivoli, Hadrian’s Villa.Laus deo. 1500 . . . day of March.

86

If the above notes on one and the same sheet were written at the same time, it may be assumed that Leonardo went to Rome on a short visit.

On 10 April 1500 Ludovico Sforza was finally defeated and taken prisoner by the French at Novara.

Leonardo comments on the events at Milan:

The Governor of the castle made a prisoner,

Visconti carried away and his son killed,

Giovanni della Rosa deprived of his money. . . .

The Duke lost the state, his property, and his liberty and none of his enterprises have been completed.

87

87

On 24 April 1500 Leonardo drew fifty gold florins from his deposit at Santa Maria Nuova in Florence, suggesting that he was now established there again. During his absence the Medici had been banished and Florence had become a more representative republic. He was probably living in the church complex of Santissima Annunziata, where his father was now procurator, as a guest of the Servite brothers. At this time he created a cartoon representing the Madonna and Child with St Anne (now lost) which so impressed the Florentines that it was viewed for two days by crowds of people.

On 11 August 1500 the marquess of Mantua received from his agent a plan of a small palace drawn by Leonardo for the merchant Angelo del Tovaglia.

A contemporary account of Leonardo’s activities occurs in a letter written from Florence dated 3 April 1501 by the Head of the Carmelites in Florence, Fra Pietro da Novellara, to Isabella d’Este in answer to questions she had put to him as to the possibility of persuading him to paint a subject picture for her ‘studio’, or failing this a Madonna and Child ‘devoto e dolce come è il suo naturale’

.

Fra Pietro writes, ‘From what I gather, the life that Leonardo leads is haphazard and extremely unpredictable, so that he only seems to live from day to day. Since he came to Florence he has done the drawing of a cartoon. He is portraying a Christ Child of about a year old who is almost slipping out of his Mother’s arms to take hold of a lamb, which he then appears to embrace. His Mother, half rising from the lap of St Anne, takes hold of the Child to separate him from the lamb (a sacrificial animal) signifying the Passion. St Anne, rising slightly from her seated position, appears to want to restrain her daughter from separating the Child from the lamb. She is perhaps intended to represent the Church, which would not have the Passion of Christ impeded. These figures are all life-sized but can fit into a small cartoon because they are all either seated or bending over and each one is positioned a little in front of each other and to the left-hand side. He is hard at work on geometry and has no time for the brush.’

.

Fra Pietro writes, ‘From what I gather, the life that Leonardo leads is haphazard and extremely unpredictable, so that he only seems to live from day to day. Since he came to Florence he has done the drawing of a cartoon. He is portraying a Christ Child of about a year old who is almost slipping out of his Mother’s arms to take hold of a lamb, which he then appears to embrace. His Mother, half rising from the lap of St Anne, takes hold of the Child to separate him from the lamb (a sacrificial animal) signifying the Passion. St Anne, rising slightly from her seated position, appears to want to restrain her daughter from separating the Child from the lamb. She is perhaps intended to represent the Church, which would not have the Passion of Christ impeded. These figures are all life-sized but can fit into a small cartoon because they are all either seated or bending over and each one is positioned a little in front of each other and to the left-hand side. He is hard at work on geometry and has no time for the brush.’

On 14 April Fra Pietro wrote again after having visited Leonardo on the Wednesday of Passion Week: ‘During this Holy Week I have learned the intention of Leonardo the painter through Salaì his pupil and some other friends of his who, in order that I might obtain more information, brought him to me on Holy Wednesday. In short, his mathematical experiments have so greatly distracted him from painting that he cannot bear the brush. However, I tactfully made sure he understood Your Excellency’s wishes, seeing that he was most eagerly inclined to please Your Excellency by reason of the kindness you showed him in Mantua, I spoke to him freely about everything. The upshot was that if he could discharge himself without dishonour from his obligations to His Majesty the King of France as he hoped to do within a month at most, then he would rather serve Your Excellency than anyone else in the world. But that in any event, once he had finished a little picture that he is doing for one Robertet, a favourite of the King of France, he will immediately do the portrait and send it to Your Excellency. I leave him well entreated. The little picture he is doing is of a Madonna seated as if she were about to spin yarn. The Child has placed his foot on the basket of yarns and has grasped the yarnwinder and gazes attentively at the four spokes that are in the form of a cross. As if desirous of the cross he smiles and holds it firm, and is unwilling to yield it to his mother who seems to want to take it away from him. This is as far as I could get with him . . .’ The painting he describes is the

Madonna of the Yarnwinder

, two prime versions of which exist, one in the collection of the duke of Buccleuch and the other in another private collection.

Madonna of the Yarnwinder

, two prime versions of which exist, one in the collection of the duke of Buccleuch and the other in another private collection.

On 19 and 24 September 1501 letters by Giovanni Valla, ambassador to Ercole I d’Este, duke of Ferrara, ask the French in Milan whether they would cede the colossal horse, which Leonardo had modelled for the Sforza monument, and which was standing neglected and exposed to wind and weather in the castle square. The French governor replied that he could not give up the model without the consent of his king.

On 12 May 1502 Leonardo, now 50 years old, evaluates drawings of antique vases from Lorenzo de’ Medici’s collection.

In the summer of 1502 Leonardo entered the service of Cesare Borgia ‘Il Valentino’, captain general of the papal armies who, with the approval of the Pope and the French king, was subduing the local despots in the Marches and Romagna to his rule. Leonardo’s role was ‘family architect and general engineer’.

Made by the sea at Piombino.

88

Made by the sea at Piombino.

88

Many years later when writing a description of a deluge Leonardo recalled his observations made at this seaside place.

Waves of the sea at Piombino all of foaming water;

Of water that leaps up at the spot where the great masses strike the surfaces;

Of the winds at Piombino;

The emptying the boats of the rain water.

89

89

During his stay at Piombino he planned the draining of its marshes.

A method of drying the marsh of Piombino.

90

[

With a slight sketch

.]

90

[

With a slight sketch

.]

He studied aerial perspective in a sailing-boat plying between the mainland and the mountainous island of Elba.

When I was in a place at an equal distance from the shore and the mountains, the distance from the shore looked much greater than that of the mountains.

91

91

Passing through Siena he examined a famous bell on the tower of the Palazzo Publico, by the side of which stood a wooden statue, coated with brass plates, which struck the hours with a hammer.

Bell of Siena, the manner of its movement and the position of the attachment of its clapper.

92

92

In June Leonardo was at Arezzo where Cesare Borgia’s

condottiere

was fighting. He was anxious to secure a book by Archimedes with his help.

condottiere

was fighting. He was anxious to secure a book by Archimedes with his help.

Borges shall get for you the Archimedes from the bishop of Padua, and Vitellozzo the one from Borgo San Sepolcro.

93

93

Had any man discovered the range of power of the cannon, in all its variety, and had given such a secret to the Romans, with what speed would they have conquered every country, and subdued every army, and what reward would have been great enough for such a service! Archimedes, although he had greatly damaged the Romans in the siege of Syracuse, did not fail to be offered very great rewards by these same Romans. And when Syracuse was taken diligent search was made for Archimedes, and when he was found dead greater lamentation was made in the Senate and among the Roman people than if they had lost all their army; and they did not fail to honour him with burial and statue, their leader being Marcus Marcellus. And after the second destruction of Syracuse the tomb of this same Archimedes was found by Cato in the ruins of a temple; and so Cato had the temple restored and the tomb he so highly honoured . . . and of this Cato is recorded to have said that he did not glory in anything so much as in having paid this honour to Archimedes.

94

94

Other books

Andre Norton - Shadow Hawk by Shadow Hawk

The Diary of William Shakespeare, Gentleman by Jackie French

Hidden Moon by K R Thompson

Wicked Flower by Carlene Love Flores

The Great Floodgates of the Wonderworld by Justin Hocking

Entromancy by M. S. Farzan

A Bug's Life by Gini Koch

A Shade of Vampire 30: A Game of Risk by Bella Forrest

Microsoft Word - Document1 by nikka