Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War (25 page)

Read Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War Online

Authors: Viet Thanh Nguyen

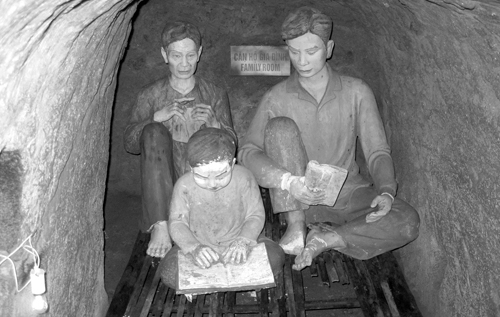

For those who call the tunnels home, the experience is not necessarily inhuman or subhuman. Tunnel life becomes heroic in memory for both soldiers and civilians. The Vinh Moc tunnels near the demilitarized zone celebrates the endurance of the local civilians who hid there and rebuilt their lives underground, complete with schools and exits to the nearby beach. The most famous of the tunnel networks, at Cu Chi, two hours from Saigon by bus, were built for war and had armories and command bunkers. In the war’s aftermath, they, as well as the Vinh Moc tunnels, have become tourist attractions for both locals and foreigners. On my first visit to Cu Chi, I traveled with a popular company whose tour guide gave a rousing rendition of the heroic revolutionary struggle of the tunnel fighters. “We were victorious!” he proclaimed on the bus, fist pumping in the air. (During a rest stop, he lit a cigarette, ordered a coffee, and told me that he was a helicopter pilot for the southern army who trained in Texas). At Cu Chi, gunfire echoed through the groves above the tunnels. At a nearby shooting range, tourists were firing weapons from the war at a dollar a bullet. Another guide in green fatigues led our tour group of mostly Westerners and some locals to a spider hole from where the guerillas had once emerged to ambush Americans. One of the American tourists actually fit into the hole. Perhaps it had been widened for the American butt, like the tunnels, which, our tour guide said, had been both widened and heightened for visiting foreigners. The foreigners laughed. When the guide invited us to descend into a tunnel, the locals, although they did not laugh, declined. Only the Westerners eased down into the dank, steamy recesses, where all that could be seen were earthen walls and the sweaty buttocks of the tourist in front of you.

Crouched in that hot tunnel, amused by the experience but annoyed by the heat, I did not appreciate that the soldiers who fought here crawled in a much more claustrophobic space, without the benefit of the light bulbs illuminating my way. The earth was musty but the reek of terror had been ventilated, the darkness dispelled, the boredom forgotten. And to what end? “They shout that they want to shape a better future, but it’s not true,” Milan Kundera says of those in power. “The future is only an indifferent void no one cares about but the past is filled with life, and its countenance is irritating, repellent, wounding, to the point that we want to destroy it or repaint it. We want to be masters of the future only for the power to change the past. We fight for access to the labs where we can retouch photos and rewrite biographies and history.”

8

In the present case, the retouched tunnels lead toward a future—there really is a light at the end, when one emerges into fresh air—and close off the past, for one cannot feel the ghosts, chased off by the electrical lighting and the curious tourists. The industry of memory’s labs dispel the ghosts of the past or tame them, as the black wall in that other nation’s white capital arguably does. The more powerful the industry of memory, the more capacity it has to amplify light and chase away shadows, to foreground the human face of the ghost and forget its inhuman face. The smaller industries of memory will try to do the same, for the weaker will also try to be more powerful than someone else, even if it is only the dead.

And yet … against the industrial memories of the great and small powers, something survives. The reason Dang Nhat Minh made his movie was that Dang Thuy Tram’s words lived in spite of the American bullet that killed her. The South Vietnamese soldier who first read her diary told his American superior, “Don’t burn it. It’s already on fire.” Every writer wants to write the book that cannot be burned, the book that is a palimpsest underneath which can be seen the shadow of a ghost. Or take the case of North Vietnamese photographer The Dinh, whose picture concludes the book

Requiem

, edited by Horst Faas and Tim Page to commemorate the photographers of all sides killed in the war. A howitzer intrudes on the left and points toward a jumble of crates and equipment. The barrel of the howitzer is parallel to a dead soldier, his body difficult to distinguish from the ruins, his face hidden or destroyed, one of his legs bent at the knee while the other is partially buried in the dirt. The fabric of his pants is darker than the fabric of the rest of his uniform. Over the landscape The Dinh’s shadow hovers. On the back of the only torn print of the photograph is this pencil-written obituary: “The Dinh was killed.”

9

As Roland Barthes and Susan Sontag have observed, photographs are recordings of the dead—not the actual dead, in most cases, but the living who will eventually be dead, and who are dead for many of the photograph’s viewers. The Dinh’s photograph is haunting because it fulfills the fatal prophecy found in the photographic genre, and because it foreshadows fatality through the self-portrait of the shadow, grafted into a picture with the obscured body of the dead. During wartime, photography’s mortal power is realized most graphically because it deals with the dead and because its artists risk death. He was only one of the 135 photographers on all sides killed during the war.

Requiem

acknowledges that although seventy-two of the dead photographers were North Vietnamese, it is mostly the photographs of the Western and Japanese photographers that survive. The inequities of industrial memory are evident in both death and art. Westerners and Japanese could airlift their film to labs on the same day it was shot, but the film of the North Vietnamese photographers was often lost along with their lives. In The Dinh’s case, this self-portrait of a shadow, this premonition of his own ghost, is his only surviving work. The ghostly absence of the Asian photographers is even more visible in their biographies, one of the most poignant sections of the book. While substantial obituaries are devoted to the Western photographers, the words given to the South Vietnamese, North Vietnamese, and especially the twenty Cambodian photographers are so brief they often amount to no more than epitaphs. One Cambodian named Leng is not unusual in having no birth or death date, his entire career described thus: “A freelancer with AP, Leng left no trace.”

10

Except for the trace of his absence. One encounters the haunting absence again in a window looking down on a stairway of the Vietnamese Women’s Museum of Hanoi. In the tinted glass stands a blank space in the shape of a woman from a famous photograph, Nguyen Thi Hien, nineteen years old. The militia fighter walks away from Mai Nam’s camera, looking over a shoulder on which is slung a rifle, her hair under a conical hat. The photograph became an emblem in the world imagination of 1966 for how “even the women must fight.” But in the museum, her photo, marked by her presence, has become an absence in the form of the blank space. That absence inadvertently symbolizes how the Vietnamese Women’s Museum, crowded with words and images of the heroic lives of Vietnamese women, cannot help but be a reminder of how that heroism is far in the past. The girl in the photograph has vanished, as has the revolution itself, now only a memory, a cutout, an empty tracing in a communist state running a capitalist economy. The museum proves what Paul Ricoeur argues, that memory is presence that evokes absence. While a memory is present in our minds, it inevitably points to what is no longer there but in the past.

11

Industries of memory seek to turn this absent presence of memory, always and forever elusive, ghostly, invisible, and shadowy, into what one could call the present absence of characters, stories, movies, monuments, memorials. These icons assume the comforting stability of flesh, stone, metal, and image, animated by our knowledge of the absence toward which their comforting presence gestures.

The relationship of absence to presence is the invisible dimension of the asymmetry of memory, existing beside the visible dimension of great powers dominating smaller ones. Whether a country is great or small, each one’s war machine and industry of memory seeks to establish control over memory itself. But what is stronger in this asymmetrical relationship, industrial memory or the absent presence of the past? The war machine or the ghost? The war machine seeks to banish ghosts or tame them, but unruly specters abound, if one looks carefully, if one recognizes that spirits exist to be seen by some and not by others. I encountered them in Laos, a country whose mere mention brought light to the eyes of the many Vietnamese who spoke of it as a paradise, so peaceful and calm. In some ways Laos appears to be a satellite of Vietnam, at least in the official Laotian industry of memory, which commemorates Vietnam as the country’s greatest ally. Prominent place is given to the Vietnamese flag and Ho Chi Minh in Vientiane’s museums, which follow much the same narrative as Vietnamese ones. Under the bright lights of industrial memory found in museums such as the Lao People’s Army History Museum, all white walls and chrome handrails, the presence of ghosts is weak. Their presence was likewise vague in the far caves of Vieng Xai in northwest Laos, at least in the daytime hours when I visited. The Pathet Lao took shelter here in a vast and impressive cave complex, greater than anything found in Vietnam, a subterranean metropolis replete with a massive amphitheater carved from rock. Under American bombardment, with the smells of humanity and fear, with the dust and earth falling on one’s head, with electricity faltering, the caves must have been much less tranquil than they are for the tourist whose greatest challenge is adjusting his camera for dim lighting.

Hewn from rock and fashioned into a tourist site, the Vieng Xai caves are industrial memory on a grand scale, a successful attempt to conquer the past, to banish the ghosts. Standing on the amphitheater’s quiet stage, it seemed to me that we did build these memorials to forget, as scholar James Young would have it.

12

Many of us want to forget the complexities of the past, as well as its horrors. We prefer a clean, well-lit place that features the orderly kinds of memory offered in the temples of the state, where the line between good and evil is clear, where stories have discernible morals, and where we stand on humanity’s side, the caves within us brightly lit. But even as we memorialize the dead, perhaps what we want to forget most of all is death. We want to forget the ghosts we will become, we want to forget that the hosts of the dead outnumber the ranks of the living, we want to forget that it was the living, just like us, who killed the dead.

13

Against this asymmetry of the dead and the living, the industries of memory of countries large and small, of powers great and weak, strive against ghosts. These industries render them meaningful and understandable when possible through stories, eliminating them when necessary. In most cases, though, the industries of memory avoid them. The number of places where the living remember the dead must surely be outnumbered by the places where the dead are forgotten, where not even a stone marks history’s horrors, where there are, Ricoeur says, “witnesses who never encounter an audience capable of listening to them or hearing what they have to say.”

14

But what draws our attention are those memorials and monuments, those obelisks and stelae, those parade grounds and battlefields, those movies and fictions, those anniversary days and moments of silence, those outnumbered spaces where the living can command the dead.

Sometimes the ghosts assert their authority, in consecrated spaces of memory yet to be fully industrialized. I did not feel ghosts at Vieng Xai but I did on my way to those caves, on the journey from Phonsavan, when my driver told me I should stop at Tham Phiu. Here, in another mountain cave, an American rocket strike had killed dozens of civilians. This much I knew from my guidebook. I had not intended to stop here, for I was not moved by the prospect of yet another cave of horrors, after the many caves and tunnels that I had already seen. But it was on the way, so why not? There was an exhibition hall, but fortunately I did not see it on my way to the cave. Missing the exhibit meant that I missed the official narrative that would try to tell me what to feel, and what it told me was not surprising, about the innocent civilians and the heartless Americans. The stairs and the handrail were signs enough that the cave had been prepared for tourists, though I was the only one of that kind at the moment. The four schoolgirls I encountered on the way up the mountain were not tourists but locals, making their way leisurely, giggling and snapping pictures of themselves with their phones. I made it to the cave before them, a black mouth through which a truck could be driven. Daylight threw itself a few dozen feet into the recesses, where there was no artificial lighting. There were no steps, no rails, no ropes to guide me over rough ground, unlike the killing caves of Battambang, in Cambodia. Nor, as in Battambang, was there a memorial or a shrine; nor pictures, photographs, placards, or memorials; nor a hungry boy asking to be a tour guide. At Tham Phiu, I was alone in a cave where the local industry of memory, already fragile, stopped at the threshold. I made my way to where light met its opposite and I looked into the darkness. What had it been like with hundreds of people, the noise and the stench, the dimness and the terror? What was in the void now? I stood on the side of presence, facing an absence where the past lived, populated with ghosts, real or imagined, and in that moment I was afraid.