Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War (26 page)

Read Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War Online

Authors: Viet Thanh Nguyen

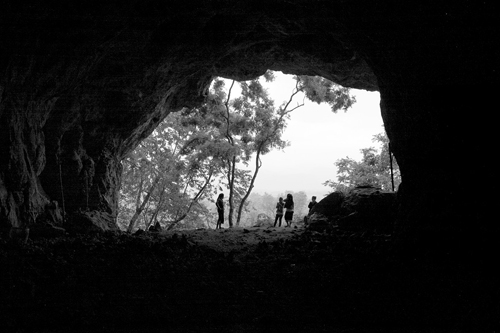

Then I heard the laughter. The girls stood at the cave’s mouth, profiles outlined by sunlight, making sure the shadows did not touch even their toes. Turning my back on all that remained unseen behind me, I walked toward their silhouettes.

7

AS A CHILD, I WAS ALWAYS AWARE

of the presence of the dead.

1

Although my Catholic father and mother did not practice ancestor worship, they kept black-and-white photographs of their fathers and their mothers on the mantel and prayed to God before them every evening. I knew the fathers and mothers of my father and mother only through their photographs, in which they never smiled and posed stiffly. In the 1980s, news of my grandparents’ passing into another world arrived one after the other, accompanied by more black-and-white photographs of rural funeral processions marching through a bleak northern landscape, of mourners dressed in simple country clothes and white headbands, of wooden coffins lowered into narrow graves. Visiting the homes of other Vietnamese friends, I paused to study the photographs of their relatives, invariably captured in black-and-white. Every household had these photographs, hallowed signs of our haunting by the past that were emblematic of a lost time, a lost place, and, in many cases, of lost people. For many refugees, the clothes on their backs and a wallet full of photographs were the only things they carried with them on their flight, “the family photograph clutched tight to a chest / When all the rest of the world burns.”

2

In the strange new land in which they found themselves, these photographs transubstantiated into symbols of the missing themselves. Photographs are the secular imprints of ghosts, the most visible sign of their aura, the closest way many in the world of refugees live with those left behind. In le thi diem thuy’s

The Gangster We Are All Looking For

, the narrator’s mother keeps the only treasured photograph of her own mother and father safe in the attic. When their home is demolished to pave the way for gentrification, the mother forgets to take the photograph with her in the family’s frantic attempt to rescue their belongings. Watching the destruction of her home, the mother calls out to her lost parents, “Ma/Ba.” The narrator, a child, listens to her mother’s cry and thinks of the world as “two butterfly wings rubbing against my ear. Listen … they are sitting in the attic, sitting like royalty. Shining in the dark, buried by a wrecking ball. Paper fragments floating across the surface of the sea. There is not a trace of blood anywhere except here, in my throat, where I am telling you all this.”

3

thuy’s book, like much of the writing, art, and politics dealing with the war, focuses on the problem of mourning the dead, remembering the missing, and considering the place of the survivors. This problem is endemic to refugees, for whom separation from family and homeland is a universal experience. Common among refugees are memories and stories of the dead, the missing, and the ones left behind, those relatives, friends, and countrymen facing the consequences escaped by the refugee. In some cases, the refugee may even benefit from telling about those consequences and the ghosts of their past. Remembering becomes imbued with the dead, freighted with their weight, a risky and burdened act. As Nguyen-Vo Thu-Huong says, “how shall we remember rather than just appropriate the dead for our own agendas, precluding what the dead can tell us?”

4

In a parallel case, Maxine Hong Kingston captures the ethical challenge for writers who speak about terrible events when she opens

The Woman Warrior

with her mother telling her, “You must not tell anyone what I am about to tell you,” a command broken in the very act of repeating it.

5

The writer and the witness face the ethical demand to speak of things that others would rather not speak of, or hear about, or pass on into memory, even if in doing so they may perpetuate the haunting rather than quell it. Reflecting upon an anonymous aunt whose suicide was the consequence of family neglect and neighborly abuse, Kingston says, “I do not think she always means me well. I am telling on her, and she was a spite suicide, drowning herself in the drinking water. The Chinese are always very frightened of the drowned one, whose weeping ghost, wet hair hanging and skin bloated, waits silently by the water to pull down a substitute.”

6

As do all writers who speak of ghosts, Kingston inhabits the fraught territory of the substitute.

For Southeast Asians who lived through the war, ghost stories were easy to come by, as memoirist Le Ly Hayslip recounts:

We found ourselves praying more often, trying to calm the outraged spirits of all the slain people around us.… Slain soldiers used to parade around the cemetery too, but whenever we kids got close, they evaporated into the mist. At night, my family would sit around and the fire and tell stories about the dead.… Consequently I began to think of the supernatural—of the spirit world and the habits of ghosts—the way others might think of life in distant cities or in exotic lands across the sea. In this discovery, I would later find I was not alone.

7

The appearance of ghosts like these becomes a matter of justice, according to the sociologist Avery Gordon. Their haunting demands that “we be accountable to people who seemingly have not counted in the historical and public record.”

8

This demand weighs heavily on those investigating the war’s aftermath, like Gordon’s fellow sociologist, Yen Le Espiritu, who declares that we must “become tellers of ghost stories.”

9

But speaking of ghosts is a dangerous act, for the storyteller must confront these ghosts, or exploit them, or return to the fatal circumstances that made them. In doing so, the storyteller must take responsibility for her tale when she invokes the dead, instead of merely claiming artistic license.

The ethical considerations for storytellers who speak of the dead and ghosts are particularly burdensome for minorities, those smaller in numbers or power. Thinking of themselves as weak or weaker, minorities may also be tempted to see themselves as victims, explicitly or implicitly. The majority may view the minority or the other as a victim, too, for that keeps the minority and the other in their places, their role to suffer and then to be saved by the powerful majority. Being a victim is a masked power that compels guilt on the part of the rescuer or the one who feels pity, but it is also a trick played on the victim for the victim’s supposed benefit. To see oneself only as a victim simplifies power and excuses the victim from the obligations of ethical behavior in politics, warfare, love, and art. Being a victim also forecloses the chance to wield real power, which the majority is not inclined to grant the minority and the other, offering them instead victimization and voice, two doors into the same trap. Ethics forces us to examine the power that we wield and the harm we ourselves can do, the dilemma that when one acts or speaks, even in the service of ghosts, one can be victimizer and victim, guilty and innocent.

Writers, artists, and critics can inflict various kinds of harm with the symbolic power they wield; so can minorities and their advocates do damage. Harm is a consequence of holding power, and even minorities and artists have some measure of power. Raising the issue of how a minority can inflict harm acknowledges that a minority is a human and inhuman agent, not merely a powerless victim, a passive subject in history, or a romanticized hero. Thinking of minorities as being human and inhuman complicates the usual stances of a patronizing, guilt-ridden majority as well as many advocates for minorities, both of which prefer to see the minority as human. So it is that when advocates for minorities speak of them taking up power, they often mean power being used as resistance against abusive power, an act with greatly reduced moral and ethical complication. The possibility of the minority possessing power with all of its confusing and contradictory implications, including the negative and the damaging, may be forgotten or overlooked in the temptation to see the minority as the victim of abusive power. While a minority’s power is not equal to the majority’s power, the minority must claim responsibility for the power it does possess, the power it must have if it can resist and, ultimately, liberate itself. In the recent past, the Western Left, so keen on the cry for resistance and liberation, has had the luxury of not actually accomplishing revolution and therefore suspending the confrontation with what it means for the wretched of the Earth to have power. Thus, if there is one thing that the revolutions in Indochina can teach the West, it is that resistance and liberation have unforeseen consequences. Those who have been damaged can, when they come into power, damage others and make ghosts.

Vietnamese Americans offer a paradigmatic example of the problems of telling on and about ghosts. Of all the Southeast Asians in America, they have written the most literature and have the longest literary tradition. French colonial policies encouraged this tradition, with the French favoring the Vietnamese over Cambodians and Laotians for the colonial bureaucracy, a practice that inevitably cultivated a literary class. The Vietnamese also benefitted from a more intense extraction of their frightened population at the end of the war, vastly outnumbering Cambodian and Laotian refugees. Both in terms of the superiority of numbers and literary education, the Vietnamese in America are a politically engineered demographic who possess much greater cultural capital than Cambodian and Laotian refugees. Their literary output can and should be judged, then, by the highest standards of ethics, politics, and aesthetics, for they have had some advantages to balance their war-born disadvantages. Thus their literature serves as an ideal test case for how the use of victimization and voice has come to dominate the aesthetics of minority literature in America. By aesthetics, I mean the process by which beauty is created and studied, which, in the case of victimization and voice, is difficult to separate from the issue of ethical responsibility. In the realm of ethnic storytelling, the ethical and aesthetic reluctance to confront one’s power is manifested through not telling on one’s own side while reporting on the crimes of others and the crimes done to one’s own people. But only through telling on how one’s own side has made ghosts can one stop being a victim and assume the full weight of humanity, which includes the burden of inhumanity.

Telling on others and ourselves is perilous, not least of all for the artists who confront the victimization that would silence them and the lure of having a voice that promises to liberate them. Claiming a voice—that is to say, speaking up and speaking out—are fundamental to the American character, or so Americans like to believe. The immigrant, the refugee, the exile, and the stranger who comes to these new shores may already have a voice, but usually it speaks in a different language than the American lingua franca, English. While those who live in what the scholar Werner Sollors calls a “multilingual America” speak and write many languages, America as a whole, the America that rules, prides itself on trenchant monolingualism.

10

As a result, the immigrant, the refugee, the exile, and the stranger can be heard in high volume only in their own homes and in the enclaves they carve out for themselves. Outside those ethnic walls, facing an indifferent America, the other struggles to speak. She clears her throat, hesitates and, most often, waits for the next generation raised or born on American soil to speak for them. Vietnamese American literature written in English follows this ethnic cycle of silence to speech. In that way, Vietnamese American literature fulfills ethnic writing’s most basic function: to serve as proof that regardless of what brought these others to America, they or their children have become accepted, even if grudgingly, by other Americans. This move from silence to speech is the form of ethnic literature in America, the box that contains all sorts of troubling content. After all, what brought these so-called ethnics to America are usually difficult experiences, and more often than not terrible and traumatizing ones.

We might say that the form or the box is ethnic, and its contents are racial.

11

The ethnic is what America can assimilate, while the racial is what America cannot digest. In American mythology, one ethnic is the same, eventually, as any other ethnic: the Irish, the Chinese, the Mexican, and, eventually, hopefully, the black, who remains at the outer edge as the defining limit and the colored line of ethnic hope in America. But the racial continues to roil and disturb the American Dream, diverting the American Way from its road of progress. If form is ethnic and content is racial, then the box one opens in the hopes of finding something savory may yet contain that strange thing, foreign by way of sight and smell, which refuses to be consumed so easily: slavery, exploitation, and expropriation, as well as poverty, starvation, and persecution. In the case of Vietnamese American literature, the form has become aesthetically refined over the past fifty years, but the content—war—remains potentially troublesome and volatile. Race mattered in this war, but to what extent it mattered continues to cause disagreement among Americans and Vietnamese. One can draw a distinction here between the two faces of one country, the United States and America. If the United States is the reality and the infrastructure, then America is the mythology and the façade. Even the Vietnamese who fought against the Americans drew this line, appealing to the hearts and minds of the American people to oppose the policies of the United States and its un-American war. As for Americans, they, too, see this line, although what it means exactly is a subject of intense debate. Many Americans experienced and remember the war as an unjust, cruel one that betrayed the American character. Many other Americans view the war less as a betrayal and more as a failure of the American character. But the number of Americans who think the war expressed a fundamental flaw in the American character, as a gut-level expression of genocidal white supremacy, is a minority.