Octopus

Authors: Roland C. Anderson

Plankton, poem copyright Joan Swift, reproduced in Fertile Fjord: Plankton in Puget Sound, by Richard M. Strickland. University of Washington Press/Washington Sea Grant, Seattle: Puget Sound Books, 1983. Excerpted by permission of Joan Swift.

Copyright © 2010 by Jennifer A. Mather, Roland C. Anderson,

and James B. Wood. All rights reserved.

Published in 2010 by Timber Press, Inc.

| The Haseltine Building | 2 The Quadrant |

| 133 S.W. Second Avenue, Suite 450 | 135 Salusbury Road |

| Portland, Oregon 97204-3527 | London NW6 6RJ |

| timberpress.com | timberpress.co.uk |

Second printing 2011

Printed in China

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Mather, Jennifer A.

Octopus : the ocean's intelligent invertebrate / Jennifer A. Mather, Roland C. Anderson, and James B. Wood. â 1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-60469-067-5

1. Octopuses. I. Anderson, Roland C. II. Wood, James B. III. Title.

QL430.3.O2M38 2010

594'.56âdc22

2009041311

A catalog record for this book is also available from the British Library.

For Lynn

Contents

Introduction: Meet the Octopus

Â

1: In the Egg

Â

4: In the Den

Â

6: Appearances

Â

8: Personalities

Â

9: Intelligence

Postscript: Keeping a Captive Octopus

Preface

O

ctopuses are intriguing and unpredictable, and our decades of studying them have given us truly exciting experiences. In fact, we three authors could have a competition for “peak octopus experience.” Was it when Roland watched the giant Pacific octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini) named Olive (she mated with Popeye) tend her eggs until they hatched out in Puget Sound? Or was it when James, as a teenager, thought his self-caught octopus had “escaped” from the tank for three days, and then found it still in the tank but underneath the gravel filter plate? Then there was the event when Jennifer first witnessed tool use by the common octopuses (Octopus vulgaris) of Bermuda. Or maybe it was when Roland, still skeptical about octopus play, phoned Jennifer long-distance after watching an octopus blow jets of water at a floating pill bottle, causing the object to make circuits in its aquarium tank, and said, “She's bouncing the ball!” Perhaps it was when James managed to raise the elusive spoon-arm octopus (Bathypolypus arcticus) for the first time. For all of us, it was also when we looked directly at a camouflaged octopus, realized it looked exactly like the rock behind it, and wondered how the animal could do that. In this book, we share many of these captivating experiences with our readers.

Octopuses are found in most of the habitats in the ocean, and they are an important part of the sea's complex web of life. They do countless interesting things, and in the process challenge how we think about such issues as personality, intelligence, or play, thereby revealing much to us about what it means to be a living being on the earth. But most important, octopuses are wondrous to behold.

The three of us have studied the octopus and its behavior, in the lab and in the field at different locations on the planet, such as Banyuls on the southern coast of France, the islands of Bermuda, the small Caribbean island of Bonaire, and Hawaii. We all started out as what James calls “old-fashioned naturalists,” walking and swimming along the shoreline and

getting acquainted with what lives thereâJennifer on Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Roland on Puget Sound, Washington, and James in Florida. We started our university educations in biology, getting a foundation in the basics of marine animals, but our paths and major interests diverged somewhat after that.

In graduate school, Jennifer started studying the Caribbean pygmy octopus (Octopus joubini/mercatoris) but switched to psychology, adding an emphasis on theory to her marine biology background. As a university professor, she has explored theoretical ideas in areas such as octopus foraging strategies, personalities, intelligence, and consciousness, and she covers these topics in this book. Roland has worked for the Seattle Aquarium for over thirty years, getting a good grounding in issues of animal care. He's written papers about enrichment for octopuses in captivity, and, in a later part-time doctoral program, he focused on the sand-digging behaviors of stubby squid (Rossia pacifica). His background in these practical areas shows when he discusses many dimensions of octopus life in this book. James completed a doctoral program in biology and oceanography, accomplishing the technically demanding task of keeping the deep-sea spoon-arm octopus and evaluating influences on lifespan. He's on the staff at the Aquarium of the Pacific, in Long Beach, California. Besides becoming an expert on keeping octopuses in aquariums and writing this book's section on the topic, he became interested in the Internet mode of communication, and formed the Web sites The Cephalopod Page and CephBase about living cephalopods. James is also an excellent underwater photographer, and many of the pictures in the book are his.

Together, we hope to help readers understand more about the mysterious marine world and the fascinating octopuses that live in it.

Acknowledgments

W

e would like to thank Roy Caldwell, John Forsythe, NOAA, Leo Shaw, Barry Shuman, Abel Valdiva, and Stuart Westmorland for providing photographs. We would also like to thank Elena Hannah, Sandra Palm, David Sinn, Kimberley Zeeh, and Brandi Walker for reading and commenting on book chapters. We also would like to thank Leanne Wehlage-Ellis for word processing. Foremost, we would like to acknowledge the octopuses for their inspiration.

Introduction

Meet the Octopus

O

ctopuses are amazing animals. They can change color, texture, and shape. They have three hearts pumping blue copper-based blood, and are jet powered. They can squeeze through the tiniest of cracks and disappear behind a cloud of ink. Octopuses adapt to new situations, solve problems, learn techniques, and are curious about their surroundings. They are considered by many to be the most intelligent of invertebrates. They have the manipulative ability to get into fishermen's crab traps, eat the crabs, and get out again. They can dismantle the aquariums they are kept in, and escape. They can even grow a new arm when one is bitten off.

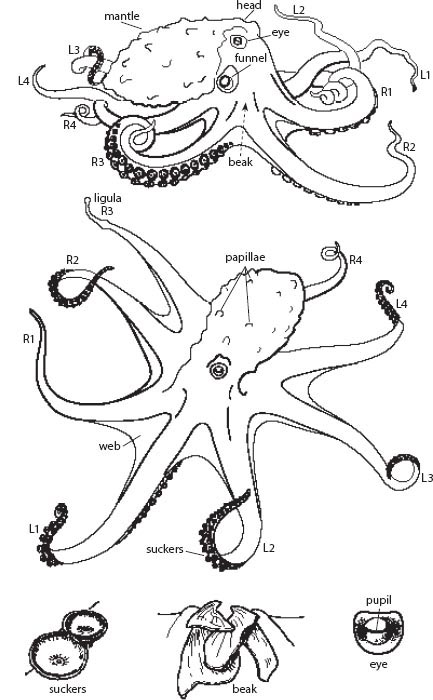

The octopus is a mollusk, like clams and snails. Through evolution, it has lost the confining but protective shell. Since it is not hidden in the shell, the muscular mantle wrapped around the animals' insides is free to set up jet propulsionâit can contract to shoot water through its flexible funnel (see plate 1). With jet propulsion, the octopus can move through the water, shove aside sand and small rocks to clean out a home, and jet at annoyances like scavenging fish and pesky researchers. The octopus's head is usually raised up high so it can see well through its two lens-type eyes, which are very much like the eyes of mammals and birds except the pupil is a horizontal slit instead of round. The head is surrounded by eight arms that have flexible skin webs between them, and the mouth is underneath at the center of the arms. To name the octopus arms, we divide them into left and right arms by their position compared to a line down the middle of the animal. If an octopus is facing forward with its mantle to the rear, it has four arms on its right and four on the left. These are counted as R1, R2, L1, L2, and so on.

The fluid in the octopus's mantle cavity is an inside part of the outside ocean, vital for respiration and removal of waste. Water circulates around in it as in other mollusks, and its contraction is parallel to our breathing. The tubelike funnel directs the outgoing water after it has passed over the gills and delivered oxygen to the blood, and it expels body wastes in its stream.

External anatomy features of female (above) and male (below) giant Pacific octopus (

Enteroctopus dofleini

). Marjorie C. Leggitt.

Because of this body arrangement, these marine animals are classified as cephalopods (“head-foots” in Latin) and named octopuses because of their eight arms (octopus means “eight-footed”), and they are also bilaterally symmetrical, with left and right sides mirroring each other, like in humans. The third right arm of adult male octopuses is modified to pass spermatophores, or sperm packets, to the female. Because the arms are lined with suckers along the underside, octopuses can grasp anything. And since the animal has no skeleton, it can flex its arms and move them in any direction. The arms aren't tentacles: tentacles are used for prey capture in squid, and these arms, with their flexibility, are used for many different actions.

Octopuses are found in all oceans at every depth and in many different marine habitats. Although we don't know exactly how many species of octopus exist, we think there are approximately 100 members of the genus Octopus, and probably about 300 octopods (members of the order Octopoda) around the world, and some do not yet have common names. Names aren't the only thing missing in the puzzle about octopuses: scientists are still piecing together their behavior, ecology, and physiology. We have seen juvenile common octopuses (Octopus vulgaris) in shallow tide pools in Bermuda and large giant Pacific octopuses (Enteroctopus dofleini) crawling out of the water to get over a rock jetty on the North Pacific coast. Some, such as the spoon-arm octopus (Bathypolypus arcticus), are adapted to the ocean's dark, cold depths up to 3000 ft. (1000 m) below the surface and can be found on the abyssal plain stretching across the bottom of the sea. Hawaiian day octopuses (Octopus cyanea) are found on shallow coral reefs, and argonauts (Argonauta argo) drift in the open ocean. The long-armed Abdopus aculeatus, which has no common name because it is so little known, crawls through near-shore sea grass beds in the eastern Pacific. The specialized deep-sea vent octopus (Vulcanoctopus hydrothermalis) is found, as its name suggests, near deep-sea hydrothermal vents way down at 6000 ft. (2000 m).