On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears (14 page)

Read On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears Online

Authors: Stephen T. Asma

But a heavier burden of explanation falls to Augustine and Isidore because, if God made matter, then he must have

wanted

these monsters to exist. In Western monotheism God cannot get off the hook by complaining of stubborn, unaccommodating building supplies. Hermaphrodites, conjoined twins, all birth defects, and a slew of monstrous races must be, as Isidore claims, expressions of God’s will because nothing, after all, is outside of God’s will. The medievals embarked on a rich speculative tradition that tried to articulate what God

wanted

when he made monsters. What was his purpose?

If giants, for example, expressed God’s divine will, then what was God up to when he made them? Augustine suggests that giants exist in order to fall. The bigger they are, the harder they fall. Augustine writes, “It pleased the Creator to produce them, that it might thus be demonstrated that neither beauty, nor yet size and strength, are of much importance to the wise man, whose blessedness lies in spiritual and immortal blessings, in far better and more enduring gifts, in the good things that are the peculiar property of the good, and are not shared by good and bad alike.”

9

The point of being a giant, then, is to overreach and fail, and in that failure highlight their corruption to others as a cautionary tale and consolation. Notice that Augustine’s theory applies to beautiful people as well as the vertically prodigious giants. Based on the same logic, they too will ultimately demonstrate their flawed unen-during rank to the uglier but more spiritually righteous. Extraordinary people, or should I say fabled extraordinary people, are at once flattened into one-dimensional morality lessons by this symbolic approach, a confident approach that applies beautifully to people you’ll never actually meet. But this moralizing tendency gets stronger and more pernicious when it spreads eventually to cover other, real races and nations whom you might actually meet.

Giants, of course, were not the only monsters to cause a flurry of medieval theorizing. The old standbys from Pliny’s famous text were all on hand to pose Christian integration puzzles. Augustine and Isidore both describe the Cyclopes and the dog-headed men, Cynocephali. Augustine adds a list of favorites from antiquity, including some men with “feet turned backwards from the heel; some, a double sex, the right breast like a man, the left like a woman, and that they alternately beget and bring forth; others are said to have no mouth, and to breathe only through the nostrils; others are but a cubit high, and are therefore called by the Greeks ‘Pigmies.’ ”

10

He goes on to describe the race of men who have two feet but only one leg, the Sciopodes, and also Pliny’s Blemmyae, the men who have no head proper but a face looking out from their chest, and who apparently live south of Egypt.

11

In the late medieval period a text circulated that led many to believe that Augustine had seen Blemmyae firsthand. In a sermon entitled “Ad Fratres in Eremo,” Augustine writes, “I was already Bishop of Hippo, when I went into Ethiopia with some servants of Christ there to preach the Gospel. In this country we saw many men and women without heads, who had two great eyes in their breasts; and in countries still more south, we saw people who had but one eye in their foreheads.”

12

This passage was popular and considered to be compelling for the credulous, but we now know that it is probably a twelfth-century apocryphal fake. Anyone who was truly familiar with Augustine’s monster discussions in

The City of God

would have a hard time reconciling this so-called eyewitness account. Yet the passage was influential in the folk culture of late medieval Europe.

Umberto Eco offers a wonderful speculative description in

Baudolino

of the Sciopodes and Blemmyae. In search of the mythical kingdom of Prester John, Eco’s fictional characters encounter the monstrous races. A Sciopod surprises the travelers: “It had a leg, but only one. Not that the other had been amputated; on the contrary, the single leg was attached naturally to the body, as if there had never been a place for another, and with the single foot of that single leg the creature could run with great ease, as if accustomed to moving in that way since birth.” Eco fleshes out the medieval descriptions and pictorial traditions by describing the creature’s foot as twice the size of a human’s, but “well shaped, with square nails, and five toes that seemed all thumbs, squat and sturdy.” The monster in Eco’s story is handled charitably, as in the Augustinian tradition. The Sciopod is described as being “the height of a child of ten or twelve years; that is he came up to a human waist, and had a shapely head, with short, bristling

yellow hair on top, a pair of round affectionate eyes like those of an ox, a small snub nose, a broad mouth that stretched almost ear to ear and revealed, in what was undoubtedly a smile, a fine and strong set of teeth.” Eco’s description of the Blemmyae is also worth quoting because it crystallizes many historical descriptions: “The creature, with very broad shoulders, was hence very squat, but with slim waist, two legs, short and hairy, and no head, or even neck. On his chest, where men have nipples, there were two almond-shaped eyes, darting, and beneath a slight swelling with two nostrils, a kind of circular hole, very ductile, so that when he spoke he made it assume various shapes, according to the sounds it was emitting.”

13

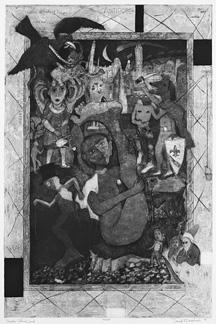

The contemporary artist David F. Driesbach portrays some of the monstrous races, including the Sciopodes, the Blemmyae, and the Cynocephali. “Prester John’s Land,” color intaglio print (1995, 35 ¾ × 23 ¾). Reprinted by kind permission of the artist.

Isidore, who was one of Eco’s sources, fuels the natural history of monsters by listing the Antipodes, whose feet point backward, locating their home in Libya. The dog-headed men, Cynocephali, are reaffirmed to live in India, and the Sciopodes are located in Ethiopia. “In the remote east,” Isidore explains, “races with faces of a monstrous sort are described.

Some without noses, with formless countenances; others with lower lip so protruding that by it they shelter the whole face from the heat of the sun while they sleep; others have small mouths, and take sustenance through a narrow opening by means of oat-straws; [a] good many are said to be tongueless, using nod or gesture in place of words.”

14

He also describes the Satyrs as homunculi with upturned noses, who “have horns on their foreheads, and are goat-footed, such as the one St. Anthony saw in the desert.” Here Isidore refers readers to the then well-known legend of the early Christian hermit, St. Anthony, who encountered a strange Satyr in the desert. When Anthony asked the Satyr who he was, the creature responded by saying that he was only a mortal beast, whom locals in their pagan ignorance had mistaken for a spirit or god. The Satyr was excited to learn more about Jesus Christ and the true God, leading Anthony to exclaim, “Woe to thee, Alexandria [a stronghold of pagan beliefs]! Beasts speak of Christ, and you instead of God worship monsters.”

15

This brings us to an important question regarding medieval monsters: Do they have souls? The Latin word for soul,

anima

, and the Greek,

psyche

, have descended to the present, giving us two different aspects of the soul concept. On the one hand, the soul is that which animates creatures; it is the principle of life and distinguishes animals from inanimate objects. But

soul

is also used more narrowly to express the uniquely human psychology, the inner cognitive self. It is fair to say that the ancients stressed the more general meaning, of the soul as the principle of life, whereas thinkers in the medieval world confined their interests to the more narrow sense of the soul as a uniquely human “divine spark.”

While Christian, Jewish, and Muslim scholars constructed a primarily religious notion of the soul as allowing one to live on after death, they also grafted this idea onto earlier Greek concepts. From Augustine to Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) and beyond, Christian philosophers interpreted the Genesis passage in which God makes man “in his own image” as a description of God’s creation of the human mind. The human mind, a little fractal form of God’s mind, was considered to be the most godlike part of the human being. In

Confessions

Augustine writes, “But that he judgeth all things, this answers to his having dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowls of the air, and over all cattle and wild beasts, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth. For this he doth by the understanding of his mind, whereby he perceiveth the things of the Spirit of God; whereas otherwise, man being placed in honor, had no understanding, and is compared unto the brute beasts, and is become like unto them.”

16

Eight centuries later, in the

Summa Theologica

, Aquinas argues that intellectual creatures are, properly speaking, made in

God’s image.

17

In this emphasis on rationality, the Church fathers were following Aristotle’s original lead.

In

De Anima

, Aristotle offered a rather naturalized description of the soul and its distribution in the animal kingdom. The soul was a broader concept and applied to all living things, not just the apex of creation. But the Stagirite recognized that souls come in varying styles and degrees. Plants, for example, have “nutritive souls,” that is, they have the power to take in food and grow. They differ from rocks and sand and iron by dint of this additional physiological potential. Animals obviously have this power too but represent a new class of creatures in their ability to move around and to feel sensations. This level of soul, up a step from mere growing potential, brings the powers of locomotion and sensation and distinguishes dogs, monkeys, fish, and every other animal from trees and plants. The relation of soul categories is asymmetrical because every animal, every sensate soul, also has the soul capacities, the physiological powers, of a plant, but

not

vice versa. The crowning potentiality of the soul is realized only in the human species, and this is the power to reason. Aristotle has no creation story such as Genesis to explain why this is so; in fact he doesn’t seem very interested in the origin of this distribution of the rational soul. He merely empirically describes the natural world as he finds it.

These days most people think about the soul as a thing, a substance of some sort. Whether you’re a believer or a skeptic, you probably imagine some rarified nouminous spirit inhabiting the mechanical body. Thinking of the soul as an entity is inevitable when the traditional metaphors refer to the soul as the captain of a ship or a ghost inside a machine.

18

But as we can see in the works of Aristotle, an equally old tradition argued that the soul is more like a

function

than a

substance

, more like a physiological

activity

than a

thing

. This is important with regard to monsters.

For medieval intellectuals, who carried on and modified the ancient philosophies of soul, monsters were just extreme cases of the larger metaphysical question regarding the status of animals. What creatures are capable of redemption? Which have souls, and how do we know? St. Aquinas, for example, concludes that animals do indeed have sensate souls (i.e., can feel pain, pleasure, etc.), but they lack reason. Animals don’t innovate and problem-solve in the same way humans do: “That animals neither understand nor reason is apparent from this, that all animals of the same species behave alike, as being moved by nature, and not acting on any principle of art: for every swallow makes its nest alike, and every spider its web alike. Therefore there is no activity in the soul of dumb animals that can possibly go on without a body.”

19

Add to this argument the typical Thomist logic: humans regularly contemplate immortal life and crave it, but animals

cannot do so because they are trapped in the play of immediate stimuli and cannot apprehend themselves in the far distant future.

20

In other words, without

reason

, a creature cannot attain immortality.

This philosophy gives us a sense of how the scholastic mind understood monsters: if they have souls, then they can attain immortality. But candidates for redemption have a downside: they are capable of sinning. In other words, having a soul implies that one has agency. In what category do monstrous dog-headed men or men with a face in their chest fall?

Augustine’s answer is refreshingly charitable: “Whoever is anywhere born a man, that is, a rational mortal animal, no matter what unusual appearance he presents in color, movement, sound, nor how peculiar he is in some power, part or quality of his nature, no Christian can doubt that he springs from that one protoplast. We can distinguish the common human nature from that which is peculiar, and therefore wonderful.”

21

Using the Aristotelian criterion, the essential definition of

rationality

, Augustine decides that the monster question is an empirical one. If the creature displays rationality, then it is, despite its horrifying appearance, a kind of human. Entailed in that humanity is the potential for redemption, immortality, and legal and moral standing. This is an impressive tolerance for otherwise repellent creatures.