On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears (35 page)

Read On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears Online

Authors: Stephen T. Asma

Predator-prey and host-parasite relationships are more detailed and documented than ever before. The contemporary imagination is flooded with images of the macabre side of nature, and our own bodies seem to be battlegrounds for viruses, bacteria, and other immunological nightmares. Not all the monsters inside us are psychological, but of course the sense of vulnerability stemming from this new biology is psychological.

Should we thank the

E. coli

in our gut that helps us to digest? Should we alternatively blame the virus that is breaking down our immune system and spreading through the host population? These organisms are not evil or noble creatures, intentionally wreaking havoc or health; they are simply doing what comes naturally, surviving and reproducing. This is not meant to sound callous or insensitive, for it is obvious that our struggle with other organisms matters a great deal to us, causing real despair. But from the more general evolutionary perspective, this drama is value-neutral.

Many science fiction horror films explicitly recognize this metaphysical position and build it into the deranged scientist character, who respects the adaptive power of the alien creature even as it devours his comrades and himself. The increasingly detached Dr. Carrington of the film

The Thing

(1951) proclaims a number of dialogue gems, many of which have echoed throughout this genre’s films, including “There are no enemies in science, only phenomena to study.” In a soliloquy to the alien at the end of the film, Carrington gushes about the superiority of this magnificent monster species, whose adaptive powers are far beyond our own. The alien responds to this admiration, of course, by bludgeoning the good doctor.

Legions of mad scientists from sci-fi monster stories act as personifications of the Darwinian metaphysic. Our culture betrays its uneasiness with the Darwinian paradigm by making these characters slightly insane

and definitely dangerous. These mad scientists understand the value-neutral character of natural selection; they understand that humans have no exalted place and are not insulated from a process that might eventually lead to their extinction. And they understand that this process knows nothing and cares nothing about the human tragedy that may result. The aliens of these films are destroying and even torturing human lives, but always inadvertently. Human suffering, in this genre, is an unintended outcome of the predator’s natural survival and reproductive techniques. It is this quality of innocence preceding the aliens’ destructive consequences that invokes the peculiar admiration of the scientists in these films. It also prevents us from applying the old lexicon of “evil” to these monsters.

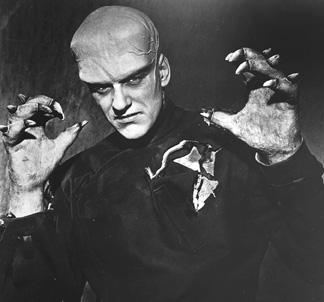

The original “thing,” part animal, part vegetable, all sinister. From Howard Hawk’s 1951 classic

The Thing from Another World

(RKO, Turner Broadcasting). Image courtesy of Jerry Ohlinger.

Recent horror, from Lovecraft to Cronenberg to H. R. Giger, tries to give us a subjective participatory experience of vulnerable flesh rather

than just a spectator’s observation. The films make our skin crawl. The influence of evolutionary and paleontology data is clear in earlier bio-horror such as

King Kong

(1933),

Godzilla

(1954), and

Them

(1954),

39

but a creepier focus on nauseating reproduction, disease, injury, and decay seems to have risen to dominance in the last quarter of the twentieth century. David Cronenberg’s 1979 film

The Brood

and Ridley Scott’s 1979 film

Alien

are good examples of this disturbing mixture of reproduction anxiety, parasite monstrosity, and human vulnerability. The scene in which Scott and Giger’s chest-bursting alien appears, “fanged, phallic, and fetal,” seems to have shaped over three decades of subsequent monster aesthetics.

40

Was the film itself shaped by larger social anxieties surrounding abortion and reproductive rights during the 1970s? Are the current films and novels about apocalyptic, monstrous disease epidemics the result of contemporary anxieties over biochemical warfare? Do Americans feel more vulnerable after 9/11 and now seek to exorcise those emotions via torture porn? One suspects that the correlations are not entirely accidental.

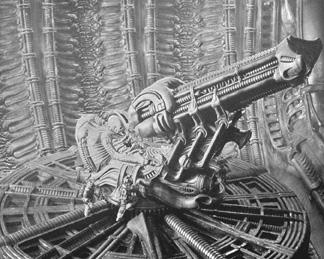

The aesthetic created by H. R. Giger for Ridley Scott’s 1979

Alien

(20th Century Fox) continues to set the tone for a whole genre of films interested in exploring the vulnerabilities of post-Darwinian biology. Image courtesy of Jerry Ohlinger.

THE MORE HARDCORE

F

REUDIAN ARGUMENT

eschews specific sociopolitical contextualization. In every civilization, emerging adolescent sexuality is always fraught with intense repression pressures, so that new and powerful libidinal impulses cannot be straightforwardly fulfilled. According to Freud, the urges themselves and their hard-won containment involve a high degree of aggression. In this view, torture porn is just an increasingly efficient catharsis of built-up adolescent sexual energy; thus it is unsurprising that the target demographic audiences for such films are teenagers.

MY GOAL IN THIS CHAPTER HAS BEEN TO EXPLORE

the recent emphasis on the subjective emotional and cognitive aspects of monsterology, aspects that parallel the rise of psychology and underscore the philosophy of human fragility and vulnerability. Monsters make up a significant part of the frightening underbelly of modernity, whether they are only hinted at in the uncanny experience or are chasing us with chainsaws. Monsters of contemporary horror are not like their medieval counterparts, who were more like God’s henchmen. That older paradigm held out the inevitability of monstrous defeat by divine justice, but the contemporary monster is often a reminder of theological abandonment and the accompanying angst. Nor are the more recent horror monsters like the monsters of the Enlightenment, products of human superstition that can be conquered by the light of reason. Monsters after Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, and Freud are features of the irrevocable irrationality inside the human subject and outside in nature.

Criminal Monsters

Psychopathology, Aggression,

and the Malignant Heart

MONSTERS IN THE HEADLINESYou’re presenting him like a monster, and he wasn’t. He was anything but a monster

.

JESSICA BATY, REFERRING TO STEVEN KAZMIERCZAK, HER

BOYFRIEND, WHO WENT ON A SHOOTING RAMPAGE AT NORTHERN

ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY IN 2008

A

S CHANCE WOULD HAVE IT

, the week I sat down to write this chapter my alma mater, Northern Illinois University, was all over the national news. On Valentine’s Day 2008 I turned on the TV and immediately recognized the building where I had once had an algebra class. Now people were being carted out of it on stretchers. A CNN news crawl at the bottom of the screen reported that eighteen or more people had just been shot in Cole Hall at NIU.

Over the next few days some facts came to light. The shooter’s name was Steven Kazmierczak. He entered a geology lecture carrying a pumpaction shotgun in a guitar case and three handguns in his belt. From the stage he began shooting into the audience, killing five people and wounding twenty others. Then he shot himself.

Kazmierczak was a former student of criminology at NIU, and he had impressed his instructors with his sophisticated research and writing. By all accounts, he was an exemplary student. Apart from some relatively tasteless

tattoos based on the horror movie

Saw

, Kazmierczak bore no marks in his personal life of any impending deviance. His girlfriend, Jessica Baty, whom he lived with, was so unaware of any threat that she perceived the early report of his heinous deed as the result of mistaken identity. “He was anything but a monster,” she said a few days later. “He was probably the nicest, most caring person ever.”

1

In 1999, after Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold killed thirteen people and injured twenty-three others at Columbine High School,

Time

magazine published a cover with photos of the killers and the headline “The Monsters Next Door.” Harris and Klebold saw themselves as avengers, paying back jocks and princesses for a high school career of humiliation and persecution.

In December 2007 Willie Kelsey was charged by authorities in Dekalb County, Georgia, with breaking into a home and shooting two children in their beds while they slept. “Willie Kelsey is one of these individuals that when you look at his record and you look at who he is, he’s just a monster among us, and thank God we got this monster off the street,” said Police Chief Terrell Bolton. In the face of such appalling inhumanity, one can’t help but grow philosophical, and Chief Bolton continued, “Anytime you live in a society where you can’t shut your doors at night and expect peace and tranquility while you sleep and somebody come in and shoot two of your children, I don’t know how else to describe anybody like that. He’s a monster among us.”

2

While we’re touring some staggering examples of deviance, consider the appalling aberration of the British sex offender Paul Beart, who in April 2000 sadistically tortured to death a waitress, Deborah O’Sullivan. Beart first assaulted his victim on the street and dragged her behind a wall, where he bit off her face and ripped open her torso with his bare hands. He also burned her with a lighter, smashed her with a trash can, broke her arm, strangled her, and sexually assaulted her.

3

For the likes of Paul Beart, even the horrible label “monster” seems much too polite and dignified.

The same revulsion seems appropriate for the Austrian Josef Fritzl, whose crime was discovered in the spring of 2008. The Austrian newspaper

Die Presse

called it the “worst and most shocking case of incest in Austrian criminal history.”

4

Seventy-three-year-old Fritzl had begun raping his daughter Elisabeth when she was only eleven, and when she was eighteen he imprisoned her in his basement fallout shelter, where he kept her for twenty-four years. Worse yet, he fathered seven children with Elisabeth, three of whom (ages nineteen, eighteen, and eleven) lived their entire lives locked in the basement with their mother; three others lived upstairs and one died at birth. He did all this while living normally upstairs with an

unknowing wife; Fritzl claimed that the upstairs children had been left on his doorstep by their long lost “runaway” daughter Elisabeth. Newspapers referred to Fritzl as the “monster who kept his daughter in a dungeon.”

The “monster” epithet is applied liberally these days to a wide variety of criminal deviants, but there is no entirely accurate profile of the modern criminal monster. By all accounts Steven Kazmierczak was nothing like the socially inept, megalomaniacal loner Cho Seung-Hui, who killed thirty-two people at Virginia Tech in 2007. And while Cho apparently claimed some sick solidarity with the Columbine killers, it seems that only the “monstrous acts” themselves unify the otherwise diverse members of the psychopathic club.

Still, the parameters of the monster epithet are not infinitely malleable, and one can assume that ordinary language users are somewhat coherent in their application of such labels. Often the label is applied to those criminals who transcend the usual or traditional motives for violent crime. Sometimes the criminal is difficult to understand because his rageful behavior is so extreme, but sometimes our bewilderment is based on the absence of

any

motive whatsoever. A criminal who kills for economic gain or for romantic revenge is odious to be sure, but at least he’s understandable in principle. Such a villain is certainly a tragedy, but still a distant relation in the human family. The label of monster, on the other hand, is usually reserved for a person whose actions have placed him outside the range of humanity.

On the south side of Chicago on May 21, 1924, Nathan Leopold, age nineteen, and Richard Loeb, age eighteen, abducted Bobby Franks, age fourteen, and murdered him with a chisel. They drove to a swampland near Hegewisch and stuffed the boy’s body into a conduit pipe under a railroad embankment. After the thrill kill, Loeb, the respectable son of the vice president of Sears and Roebuck, toyed with unsuspecting detectives by volunteering all manner of helpful theories and possible suspects. Eventually the body was discovered, as were Leopold’s nearby glasses. The glasses, together with the discovery of a matching typewriter used by Leopold to create a bogus ransom letter, led to the arrest of the affluent boys. In the introductory essay for Leopold’s later book,

Life Plus 99 Years

, the writer and creator of Perry Mason Erle Stanley Gardner explains, “Society looked upon Leopold and Loeb with revulsion and horror. Coming from good homes, they had committed a murder apparently just for the thrill. The two boys were considered monsters.”

5