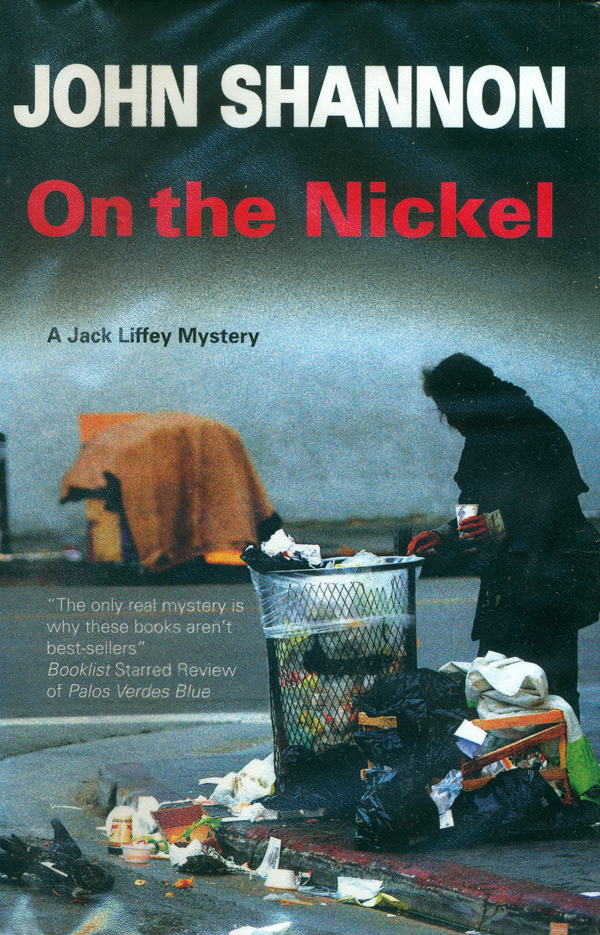

On the Nickel

Authors: John Shannon

The Jack Liffey Series by John Shannon

THE CONCRETE RIVER

THE CRACKED EARTH

THE POISON SKY

THE ORANGE CURTAIN

STREETS ON FIRE

CITY OF STRANGERS

TERMINAL ISLAND

DANGEROUS GAMES

THE DARK STREETS

THE DEVILS OF BAKERSFIELD

PALOS VERDES BLUE

ON THE NICKEL *

*

available from Severn House

A Jack Liffey Mystery

John Shannon

This first world edition published 2010

in Great Britain and in the USA by

SEVERN HOUSE PUBLISHERS LTD of

9â15 High Street, Sutton, Surrey, England, SM1 1DF.

Trade paperback edition published

in Great Britain and the USA 2010 by

SEVERN HOUSE PUBLISHERS LTD

Copyright © 2010 by John Shannon.

All rights reserved.

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Shannon, John, 1943â

On the Nickel. â (A Jack Liffey mystery)

1. Liffey, Jack (Fictitious character) â Fiction.

2. Private investigators â Family relationships â California â Los Angeles â Fiction. 3. Missing persons â Investigation â Fiction. 4. Los Angeles (Calif.). Police Dept. â Fiction. 5. Detective and mystery stories.

I. Title II. Series

813.5'4-dc22

ISBN-13: 978-0-7278-6903-6 (cased)

ISBN-13: 978-1-84751-247-5 (trade paper)

Except where actual historical events and characters are being described for the storyline of this novel, all situations in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to living persons is purely coincidental.

All Severn House titles are printed on acid-free paper.

Severn House Publishers support The Forest Stewardship Council [FSC], the leading international forest certification organisation. All our titles that are printed on Greenpeace-approved FSC-certified paper carry the FSC logo.

Typeset by Palimpsest Book Production Ltd.,

Grangemouth, Stirlingshire, Scotland.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

MPG Books Ltd., Bodmin, Cornwall.

For the novelist and critic Michael Harris: dependable friend, ambitious writer, big soul.

Deepest acknowledgements to the wonderful suggestions offered by my friend Mark Jonathan Harris and for the insights culled, with his permission, from his lovely and moving 1989 young adult novel about Skid Row,

Come the Morning.

Also to the inspiring work of

L.A. Times

columnist Steve Lopez, whose 2005 and later articles about the remarkable homeless cellist Nathaniel Anthony Ayers grew exponentially from a series of poignant newspaper columns to a book and then a movie, both called

The Soloist,

while I was working on this novel.

And finally, to the great social historian, friend and writer Mike Davis, his son Jack, and the rest of the family. They have graciously served as archetypes for the malleable and fictional Mike Lewis family through twelve Jack Liffey novels, and counting. In addition, I have been deeply influenced by Mike's groundbreaking books such as

City of Quartz

and

Ecology of Fear,

along with his other books and articles, which have suggested new and fruitful ways of looking at this strange phenomenon of Los Angeles. He has enriched my books immeasurably.

And if the city falls but a single man escapes

He will carry the City within himself on the roads

of exile

He will be the City â¦

â Zbigniew Herbert, âReport from the Besieged City'

On thinking about Hell, I gather

My brother Shelley found it was a place

Much like the city of London. I

Who live in Los Angeles and not in London

Find, on thinking about Hell, that it must be

Still more like Los Angeles.

â Bertolt Brecht,

Poems

The Raging Homeless

âI

'll be your Archie Goodwin,' Maeve offered.

Jack Liffey's brow furrowed, and it was clear he didn't know what she was talking about.

âNero Wolfe's right-hand man. Ironside had a legman, too. But I've only seen a few old reruns. Mark something. OK, I'll be your Doctor Watson, you fuddy-duddy.'

He got it. He rattled the arms of his wheelchair angrily, a tiny charade of a tantrum, one of the few ways he had of expressing annoyance, or expressing much of anything.

She gave him the zucchini and ginger curry sandwich she'd been withholding and stuck out her tongue. âYou're in my power, decrepit dad-o-mine. Better get used to it. I can play Ornette Coleman real loud. I'll dance in seven veils. I'm trying to make life a little more interesting for you. Get you a job to do.' There, she'd said it. âGive your mind a task to fasten on like a leech.'

He'd been unable to use his legs or his voice for more than a month now, since he and Maeve had been trapped under an immense slumping hillside of mud and debris, having taken desperate refuge in a bathtub when they glanced out the window and saw the brown wall coming. The mudslide had ripped open the walls of the house and pressed a brute thumb down on his spine, disturbing something within. He had lain atop her, trying to protect her, as he always did, for forty-five minutes. It had been no fun for her either, as most of that time he'd been unconscious because of a claustrophobic panic that she knew he'd been carrying around like a secret charm since falling down a well as a child. The doctors had since prodded him and spinal tapped and X-rayed and CT-scanned him no end, spoken in a mumbo jumbo of T9 and L6, but always ended up shrugging and saying that his problems were probably only psychological.

That invariably set Maeve off. âIs that what they told Hemingway when he was desperate for help? Why

only

psychological? The mind can be everything!' Doctors were pretty useless.

Her dad was scribbling furiously on his yellow pad now.

NO

TO NERO WOLFE. HATE ORCHIDS. AGREE WITH GEN. STERNWOOD. TOO MUCH LIKE FLESH OF MEN.

âWell, I like orchids,' Maeve insisted. âThey're weird and beautiful.'

They'd watched a DVD of

The Big Sleep

together the week before â just wonderful! â so she knew his referents, knew about the old general out in his hothouse who was trying to hire Philip Marlowe. Unfortunately, she hadn't been speaking theoretically, but her father remained purposely obtuse to all her hints about helping him get back on track as an investigator. His old friend Mike Lewis had called just that morning with a possible job for him â not knowing how badly off he was. It didn't look like she was going to get away with nudging him into it, and her program wasn't all altruism. She had her mind set on playing Dr. Watson. Maeve was in her last semester of high school and still unsure of a college or even a major, and a break from all that annoying future-anxiety â and a few other personal problems â would have been delightful.

Her father took a bite and nodded a reluctant appreciation of the odd sandwich. She refused to make him anything even vaguely reminiscent of animal. He opened his mouth to say something â old habits die hard â and emitted a kind of tortured squawk. GINGER ALE. He tapped his finger on the words on the second pad he kept in his saddlebag, which contained whole pages of alphabetized requisites:

BATHROOM

BED

BAD IDEA

BRING LOCO

BRING MY BOOK

COFFEE

COLDER

DOCTOR!

GET MAIL

GINGER ALE

GOOD IDEA

HATE THAT MUSIC

HOW ARE YOU

HUNGRY

KILL THE TV

KILL THE RADIO

KLEENEX

MAKE CALL FOR ME

MAKE HOTTER

NEED CHECKBOOK

NEED MY MEDS

NEW PENCIL

NEED READING GLASSES

PUT TV ON

SWEATER

TAKE LOCO AWAY

THIRSTY

TO BACK YARD

TO BED

WAKE ME IN _______

WHATS ON TV TONIGHT

WHEN

WHERE'S GLORIA

WHERE'S MAEVE

WHO CALLED

WHO VISITED

If his mute condition kept up, they'd have to get him one of those talking machines like that physicist guy, she thought. Are-we-alone-in-the-un-i-verse? She mimicked the affectless robot voice in her head.

But her dad still had use of his hands, so he could write. She kissed the top of his head. Maeve loved her father to death and would have given up her own future and stood by his side translating for him forever if he'd have allowed it, but she knew he wouldn't.

When he nodded off in the wheelchair after lunch, she went into the living room of Gloria's house, out of his hearing, and called Mike Lewis back at his home in northern San Diego County.

âMike, this is Maeve Liffey. You know, my dad got hurt pretty bad in the PV landslide. He has to sleep a lot these days, and he just went off into noddy-ville. But he asked me to call you back and get some details about the job.'

âI'm sorry, Maeve, I didn't know he was so bad. My own Prager-Sjöman's is getting worse too, I hate to say. I had to give up teaching.'

She made a horrified face that he, of course, couldn't see. Her father had never told her about this, but Mike Lewis made it sound like she should have known. And if she was to be her dad's Dr. Watson, she should know everything.

âI'm sorry, Mr Lewis. Dad told me, of course, but I've been in a null zone for a while. What is it you want him to do?'

âI know he's a damn good child-finder. Even if he's on half speed, I'd trust him ahead of just about anyone up there. My son Conor has run off, and I think he's in L.A. I usually trust Conor's judgment, pretty much, but he's still only sixteen and there's too many ways a boy can get hurt at that age. I'd like Jack to make contact if he can. Have him call.'

She knew those dangers only too well. She herself had fallen madly in love/lust with a gangbanger a year earlier and got herself beaten to a pulp joining his Latino gang, and then got herself pregnant and for quite a while had felt that she was truly lost in an alien world and would never get back.

âDad would want me to get whatever background you can give him,' she said.

âOK. Conor's quite an idealist, in all the senses. A Platonist â and the ordinary political meaning, too.'

She'd have to look up Platonist, she thought. Best to pretend she had a grasp on it right now. She wished he would give her something practical.

âHe was in a rock group, like all kids his age, but it was based on pretty erroneous affinities. The other kids were rebellious and defiant but really just suburban assholes who didn't want to learn anything. He was a lot smarter and more curious.'

âWhat was it called? It might help.'

âYou do take after Jack. The Raging Homeless.' She could hear him laugh softly. âAs if there were any homeless within fifty miles of here. As if the completely demoralized go on rages. He named it, probably acting out some version of the politics he's heard all his life, from me and Sinéad and Soledad.' He sighed audibly. âI think what might have upset him this time was my condition â I know it's tough to watch a parent decline â plus a nasty argument I had one night with Soledad. Then he had some kind of dust-up at high school. I couldn't get it out of him. Jack can check on that. Fallbrook High.'

âWhat makes you think he came to L.A.?'

âOther than L.A. being the great magnet for everything loose in the U.S.A.? The music business, I suppose. As far as I know, he has no friends there.'

âAnything else my dad should know? Is he gay, is he an anarchist, has he broken up with a girl, does he drive a chopped âfifty-eight Chevy with a supercharger?'

âYou must have interesting friends, Maeve. Conor is not gay, as far as we know; he loves soccer but he was too short and slow to be much good at it; I think his girlfriends are all still casual, and he drives our old Prius when he can borrow it. Let me think. The concept of not harming the weak and innocent is so powerful to him that he says he can't read Dickens. It hurts him physically. For a while in junior high he called himself Commie Boy and founded a collective whose only other members were a couple of disturbed twins. Their parents sent them away to a military school and phoned us in a rage, screaming that Soledad and I were an evil influence. His band is the only thing that's endured.'

âWas their music any good?'

âNot really. It was a garage band run on the old punk-rock ethos that you really shouldn't be proficient. They did pay to cut a couple of CDs and sold them on the web.'

âWould you send a picture of Conor to my e-mail? Dad still won't get a computer of his own.'

Even now,

she thought,

when it could be his lifeline.

But she didn't want Mike to know any of that. âYou know what a Luddite he is. And e-mail the names and phone numbers of some of Conor's friends.'

âWill do. I've got your address.'

âCan I tell Dad how you're doing, healthwise?'

She heard Gloria's car in the driveway and knew she had to make this quick.

âWe're hoping it's stabilized, but to put it simply, my autoimmune system is eating me up. I had to give up teaching because I can barely walk. I suppose it's just the American experience â the long slow decline in expectations. Tell Jack I miss him and to call me when he can.'

âThanks, Mr Lewis. I've got to go now.'

âAnd tell Jack we love Conor a lot and want him home.'

âI sure will.'

Notes for a New Music

Day Zero

One shouldn't make a fetish of caring for its own sake, but maybe for the sake of the world. Is there anything more powerful in the world than the loneliness of a simple soul who cares? (Whoa! â I'm getting sentimental.) I will probably never lose a girl as important to me as Tessie, but we didn't belong together, and I know it.

I wonder if I've already written the best songs I'll ever write. Dad warned me not to feel that way, that the future would always open up like a mountain vista, but he's trying so hard to hide the slow collapse of his health. The grace â the grace that man has. He is a man that I will never equal. Are sons always less than their fathers?

This is

not

the first day of the rest of my life. Today was just a bus trip, all numbnuts, burgers and suburbs, and an empty chat with a sad seatmate who got off at Oceanside to join the Marines. (I didn't say what I felt. Fuck that!) Maybe tomorrow will be the first day of the rest my life. I think I can pick whenever tomorrow starts.

I've been in a coma for years, all through school, something so horribly common in America. I guess I've chosen trouble now. Disruption. Instead of continuity. I'm sorry, Mom and Dad, but I had to make a run for it. You two are all about language and words and your obsession with reason, and you'll never understand that all those things get in the way of meaning for me.

Jack Liffey was trying to work out how to send a message to the legs that he could see down there, enclosed in chinos that were a bit wrinkled, with black postal walkers on his feet, resting like stones on the foot flaps of the wheelchair. In body sensation, most of the time he was a floating torso, though with a little buzz in his butt and even his feet now and then when he ran the chair over a rough surface. It was the strangest sensation he'd ever had, being so obviously connected to the outlying provinces of his body but the messages from out there were so weak and ineffectual. Provinces of the body in revolt. What was that poem? Auden.

In Memory of W. B. Yeats.

He ran his wheelchair carefully down the makeshift plywood ramp to the back lawn where Loco was sunning in the weak winter light. His rump felt the unevenness of the crabgrass as a vibration, faintly. Loco hadn't really adjusted either. Somehow the dog knew it all, and the beast tended to treat his immobile legs as alien objects, sometimes even barking frantically at them, as if to protect his master from them. Jack Liffey encouraged it with gesture, figuring the dog's wide-open outrage might just help somehow, loosen his own expression of ⦠what? A kind of bewildered resentment that seemed to hold him caged in his muteness, baffling and without physical cause. Or so he'd been told.

The paraplegia â that was different, somehow. A more straightforward kind of shirking that his body had taken on, in the face of the panic of claustrophobia. Being literally buried alive, entombed. Even now he had chills thinking of it. Some part of his psyche was probably still cowering in a deep inner cave, down inside himself where he had crushed and hidden away all the other things in his life that he'd fucked up.

âIt's in your mind,' the docs said. âWork on it.' But he'd be damned if he'd go back to the shrink of a few years ago who'd kept wanting him to âtake ownership' of a collapsed lung and the intermittent weeping that had been described as his âbreakdown.' Enough. He'd already passed the saturation point of thinking about his rebellious body.

I fought the mutiny,

he thought,

and the mutiny won.

He listened to the silence of his legs, their absolute heavy stillness. It had a different quality than other silences. An aggressive hush, like a belligerent drunk in a bar preparing to bludgeon someone. He swore that his legs had become smug with their new power to immobilize him.

Just one nerve impulse, legs, and I will get you back. I swear to God, when I do, I'll hurt you for this.

They laughed at him.

We give the ultimatums here,

they told him.

When you've separated all that rage from your soul, you may begin to live your life again.

He wondered if he was going mad. Imagining voices talking at him from his own body, for Chrissake.