Once Upon a Wish (27 page)

Authors: Rachelle Sparks

Some of them, whose legs were nothing but heavy, numb, useless limbs, scooted with their arms, well-defined from years of carrying themselves through life, along metal to the back of the truck as it came to a dusty halt. Others, legs missing from the knee down, just sat waiting, as they had their whole lives, for arms to lift them.

As Garrett helped them down from the truck, one by one, they looked at him with childlike eyes, much like his own that had once scanned the faces of doctors desperate to help. He smiled and they smiled back, a universal language. With the help of his parents and two others from their Globe Aware group, Garrett placed each person in his or her own wheelchair, and while some took off right away, using their arms to push the large bicycle tires on either side of their seat, others remained still, helpless, unable to grasp the idea that they could finally move freely, on their own.

Garrett watched as they circled, then pushed handles and let go, sending these people into freedom. It had been a year since surgery, a year of independence, a year without Dystonia. When he learned after his surgery that he could make a wish through the Make-A-Wish Foundation, Mike and Linda jokingly said, “We’re not going to Disney World.”

Garrett had never been, and they were not the Disney World kind of family. They were adventurers, seekers of the untraditional.

“You should consider giving back,” Linda had said, and the only thing Garrett could think to give was the best gift he had ever been given—the gift of mobility.

Garrett and his parents had traveled all over the world, journeyed unbeaten paths, taught English and math to kids in impoverished countries, and gained a deep understanding of different ways of life. They had lived in homestays, met locals in different countries, been enriched with firsthand knowledge of other cultures, but they had never fully immersed themselves, connected themselves, to the lives of the people. This was their chance.

“I wish to go to Cambodia and build wheelchairs for people who can’t walk,” Garrett had announced, and the Make-A-Wish volunteers sat still, smiles plastered, confusion setting in. They had never heard such a wish. How would they go about building wheelchairs in Cambodia? Where would they start? They contacted Globe Aware, a nonprofit that organizes service projects, and Garrett and his parents were on a plane a few months later.

“

Orkun

,” cried one woman, grabbing the bottom of Linda’s shirt after she helped her from the back of the truck. The woman looked to the ground, tears landing in the soft dirt after running down the length of her hands, pressed together in prayer.

“

Orkun

,” she cried over and over in her native tongue.

Linda smiled and looked at their translator, Dine.

“Thank you,” he said.

“You’re welcome, you’re welcome,” Linda said over and over, but the woman would not let go.

Garrett watched, the woman’s intensity rushing through him. He wanted to hear her story, wanted to know what happened to her legs. He wanted to hear all of their stories. As a group, they eventually migrated to a nearby hut with a large, open floor, straw above, a table, and nothing else. They sat in a circle and exchanged

stories, speaking slowly, deliberately, as the rest sat in total silence, Dine’s voice, his translations, echoes.

As they spoke, Garrett remembered pinning himself between a chair and his bed for hours in the middle of the night. He recalled stares in the halls of his school, disbelief from strangers, running clumsily before falling, learning to live inside his body, a perfect stranger. And then he looked at the faces surrounding him. The faces of people who had spent more than twenty years with broken legs or no legs at all, no means to get around, no “prison with wheels.”

Their prisons were their homes, places they stayed, sitting still on dirty floors—for days, months, years at a time. Their prisons did not include occasional running, the ability to jump from a wheelchair and catch a football. Their prisons did not take away their outdoor adventures, forcing them into air-conditioned homes with TVs, games, and books. They had no books. They had no TVs. They had no air-conditioning, despite cruel, hot summers, no electricity, no light.

When each of the ten people finished telling their stories, Garrett and his parents, the only people from the group who asked to visit each home, each prison, bounced in the back of the old, metal truck as it crawled along dirt roads and into the villages where these people lived. One by one, they visited each home as the setting sun chased behind with fiery reds and magnificent orange. Its persistent push limited their visits to just a few minutes each, but it was long enough to see firsthand poverty that Garrett had only ever seen from a distance.

He had once witnessed the slums of Nairobi, consisting of cardboard homes with aluminum roofs, from a highway in Kenya. He had danced with the Hadza tribe—the poorest people he had ever met—admiring their content spirits, appreciating their genuine

smiles inspired by living from the land. He had watched the children teeter-totter on tree branches, play in the dirt as though it was sand in a sandbox. He remembered how they only showered when it rained and only ate after a successful hunt.

That was poverty, but this … this was different. This was confinement in their own, dark homes, escape only possible through their minds. Leaving was not an option for them, not without the help of another. There were no cell phones to call for help, nobody to hear their shouts outside of earshot.

Garrett watched as each wheelchair recipient pushed himself or herself freely around the wooden floorboards of their stilted home, and for the first time, it didn’t seem to matter that a box in the corner used as a bed was the only piece of furniture in the room. The dust and lack of windows went unnoticed. They could move, and that was all that mattered.

All these people could see was this newfound freedom, and that’s when Garrett realized just how much he had—how much he always had. Nothing was taken from him. Without his experience, without Dystonia’s firm grip on his life, he would never be standing in the homes of these people, realizing and appreciating every single thing in his life. It was time to start looking at what he had, not at what he did not have. What an invaluable lesson to learn at sixteen. It was his trip, his wish, that taught him that.

Standing in the home of the woman who would not let go of Linda, the woman who was still thanking them, still touching their arms and insisting for them to spend the night, Garrett drank milk from a coconut she had given him and made a decision.

He decided that every vacation in the future would not just serve as a good time, would not just involve exploring and expanding his view of the world. He was going to become part of it—part of the culture, part of the people. His Wish trip opened his eyes to all that

he was capable of giving, the difference he had the ability to make. Every vacation would be a “service vacation,” and after his trip to Cambodia, Garrett graduated from high school and his first “service vacation” before enrolling at the University of South Carolina to study international business was to teach English to children in Nicaragua. His second was helping at an after-school program for street children in Peru.

After Garrett’s Wish trip, he started speaking for Make-A-Wish Foundation functions and fundraisers, helping to raise money and spread awareness of the impact wishes make in children’s lives. He gives credit to his doctors for his gift of mobility, his miracle, and thanks Make-A-Wish for letting him pass it on.

STORY FIVE

•

“My fight with PH has been long and hard, just like the fight of trees against the forces of deforestation. Trees, I endure, and so shall you.”

—Meera Salamah

1

1

W

AVES ROLLING IN

from the deepest part of the Mediterranean swelled and crashed in the distance before meeting the shore with gentle, peaceful ease. With arms stretched like wings, Meera twirled in dizzying circles through the clear, emerald green water of Lebanon’s Golden Beach,

Shat Dahabee

, and fell into its warm embrace.

A slight breeze carried the scent of the country’s most authentic dishes—fresh fish caught from the sea, hummus dip, baba ghanoush—from bamboo-roofed cafes lining the historic peninsula surrounding them. A vibrant, folksy mix of traditional Lebanese and Egyptian music flowed from those cafes, creating a cultural, celebratory vibe for beachgoers, who played soccer and made drip castles in the sand.

Meera laughed and splashed then soared from the sea as her grandfather scooped her into his arms and hurried toward the beach. She knew just what that meant.

“Where are they?” she asked excitedly, leaning over his shoulder to get a closer look. “I don’t see them, Jiddu!”

Ankle-deep, he glided carefully, patiently, through the calm waters.

“There they are,” said her grandfather, “Jiddu,” as Meera called him. “See the jellyfish?”

Meera’s long, black hair danced in the salty breeze, covering her face. She quickly swiped it away from her eyes and leaned in for a closer look.

Hundreds of these tiny, fascinating creatures bobbed gracefully below.

“

Andeel

,” he said in his native tongue, and then translated. “Jellyfish. Can you say

Andeel

, Namoora?”

He and the rest of the family had called Meera “Namoora”—the name of a sweet, Lebanese dessert—from the time she was born.

“

Andeel

,” she said proudly, excited to add another Arabic word to her four-year-old vocabulary.

“Remember the warm, salty air in your face,” Alex whispered into Meera’s ear. “The hot sand in your toes. The sound of the waves. You are playing at the beach with Jiddu.”

Eyes closed, Meera’s father blocked out the beeps, warmed his body in the cold room with thoughts of the ocean’s tepid air, breathed in memories of the water’s salty scent. His mind took him to

Shat Dahabee

, and he wanted his eleven-year-old daughter there with him.

“Fill your lungs with the warm air

,

” he said, begging.

Demanding.

“Breathe it in, Meera. Just breathe,” he whispered

.

Her body was giving up, but on some level, she heard the pleas of her father.

Alex found relief every time the numbers on the machine keeping Meera alive would jump as her oxygen level increased, indicating another breath taken. He and his wife, Nita, remained at Meera’s side, night and day, giving her orders. When her chest remained still and the numbers dropped and the beeps persisted, Alex took over for the machine.

“Breathe.”

She listened and her body responded, fighting for life.

Dr. Robyn Barst, a Pulmonary Hypertension (PH) expert at New York-Presbyterian Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital, who had been working with Meera’s doctors from the beginning, knew there were risks of the Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO)—heart and lung—machine keeping Meera alive for too long. Her body would eventually grow weak, letting the machine take over its organs.

“We need to take her off the machine and get her to New York City,” Dr. Barst said.

The first time Nita, Alex, Meera, and her younger brother, Zane, had traveled from their Dallas, Texas, home to New York was in 2004, three years before, when Meera was eight years old and first diagnosed with PH.

“Don’t worry, we’re going to beat this,” Dr. Barst had said.

It was time to find out if they would.

2

2

C’mon, you can do it,

Nita thought to herself one morning as she watched her eight-year-old daughter on the soccer field, hunched with hands on her knees, head pointed toward the ground. The other girls on her team sprinted down the field as Meera jogged to the sideline for a puff of her inhaler.

“You okay, sweetie?” Nita asked.

“Yeah, I’m okay,” Meera said, panting.

She caught her breath, inhaled once more, and let it out as she ran to join the game. She trudged up and down the field, from goal to goal, on the defense for her team, the Ladybugs.

Icy winds on that late March morning grabbed at her hair, still damp from an early-morning swim lesson, and pulled at her body as she ran against it. Determined, Meera played her heart out,

maneuvering the ball with ease, running alongside her teammates, until her run became a trot, and then a gradual walk.

Breathing the chilly air, running through its frigid grip, she came down with a severe cold a few days later. An X-ray to determine whether or not she had developed pneumonia revealed that her heart was enlarged and she was sent to a cardiologist. After hours of testing and numerous whispered conversations between doctors, they asked Meera and Zane to play in the children’s waiting area while they spoke to Alex and Nita.

“We’ve determined that Meera has a rare condition called Pulmonary Hypertension,” one doctor said with a calm voice, but there was alarm in his eyes.

Nita spent that night in front of her computer, the light of the screen illuminating the tears on her face as she scrolled and read site after site.

“No known cure.”

“Serious illness.”

“Progressive heart failure leading to death.”

One step at a time

, she thought, wiping her eyes.

We will get through this

.

The first step was telling Meera the doctor’s orders—no more physical activity, no more soccer.

“No more soccer?” she asked in alarm. Her eight-year-old life revolved around the sport. “Why not?”

Without a full understanding of the reasons she could no longer play, Meera spent her recesses at school staring longingly at the other second graders playing tag and soccer as she and her friends circled the campus, talking and sharing secrets.

One afternoon, she picked a handful of wildflowers lining the fence surrounding the playground and carefully bundled them into a bouquet.

“Treehugger!” her friends teased, and Meera smiled. She could no longer experience the outdoors the same way she once had, kicking soccer balls, running in the fresh air, but she could continue enjoying and appreciating it in the way she had learned to do after joining the school’s environmental club earlier in the year.

“All right, we’re going to build butterfly houses today,” said Mr. VanSligtenhorst later that afternoon during an environmental club meeting. Meera had joined after an environmentalist visited her elementary school and fascinated her with clothing made from water bottles and other recycled materials.

Through the club, Meera enjoyed planting flowers, learning about the rain forest, making paper, and keeping the environment clean by recycling. She painted her wooden butterfly house lime green and lavender and added bright polka dots and pastel flowers.

Once they were dry, Mr. VanSligtenhorst hung all the colorful houses from an oak tree near the playground, and Meera stood beneath them, watching in awe as butterflies fluttered through the windows and out the doors before landing gracefully on the rooftops to rest their beautiful wings. She watched carefully, intrigued by the way they seemed to study their surroundings thoughtfully, deciding what their next destination would be.

When Meera got home, she just wanted to be outdoors, in nature, with the sun and the wind. She wrapped her arms around the forty-foot-tall silver maple in her front yard that she loved for its shade and beauty and whispered, “I love you.” Sitting on its bumpy roots, she waited until the late afternoon sun took a dip beneath the horizon before pulling out her finger paints. Resting on its trunk, she began to paint the fire reds and blazing oranges of the setting sun, and it was then that she transitioned from athlete to artist.

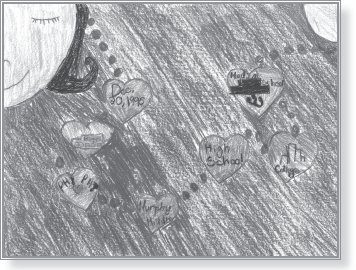

Pulling out another sheet of paper, Meera created a colorful trail of hearts all over the page. She wrote inside each heart the timeline

of her life, from birth to “Boggess Elementary, PH, Murphy Middle School, high school …”

Then she predicted her future—“college, medical school, PH doctor”—before writing on the back, “My dream is to become a PH specialist and help the young and old who have PH like me. I would like to help them follow their dreams.”

During her battle with Pulmonary Hypertension (PH), Meera created this picture—a prediction of her future, from birth to PH doctor.