One and Only (6 page)

Authors: Gerald Nicosia

At first, though, he paid no attention to the war. He was too busy listening to jazz, both the big-band swing of Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw that was then in vogue, and also the underground birth of bebop in the little after-hours Harlem clubs, where he was led by a hip Jewish kid from Horace Mann named Seymour Wyse. Once he got to Columbia, his interest in jazz continued to grow, and he'd spend much of his time in his room reading Dostoyevsky and other great books he loved. He played little football, because Coach Lou Little (Luigi Piccolo) had a different favorite running back, an Italian named Paul Governali, and Kerouac's breaking a leg on the playing field didn't help things.

Â

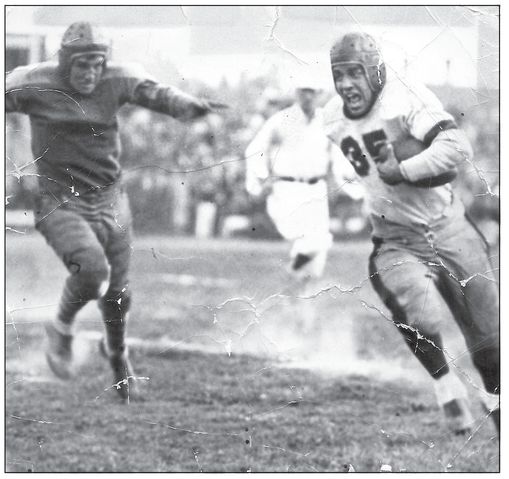

Jack Kerouac running for a touchdown for Lowell High School, fall of 1938. (Photographer unknown.)

But soon studies began to matter little to him, anyway, because he was plunging rapidly into a heady subculture of New York artistic intelligentsia, which included his future wife Edie Parker, an art student; piano-playing pre-law student Tom Livornese; would-be writers such as Allen Ginsberg and Lucien Carr; creative and unconventional college students such as Hal Chase (anthropology) and Ed White (architecture); and bookish petty criminals such as William Burroughs and Herbert Huncke. This offbeat group (pardon the pun) enjoyed the fleshly kicks of booze, drugs, and sex as much as they enjoyed high-level, soul-searching rap sessions, since they were for the most part a troubled bunch of young peopleâsome of them actual outcasts from society and their disapproving families, and some of them just feeling outcast in a world that now worshipped power in the form of atom bombs and commercial success in the form of look-alike tract houses and gray flannel suits.

In 1942, Kerouac dropped out of Columbia completely. He got kicked out of the Navy because he laid down his rifle on the drill field, announcing that he didn't want to kill anyone. He still wanted to serve his country, however, and did so in the Merchant Marine, sailing on the famed S.S. Dorchester the run before it was torpedoed by a German U-boat, resulting in the loss of nearly 700 lives. Kerouac remained patriotic all his life, but when he returned permanently to New York after yet another dangerous merchant voyage, he was embittered and feeling let down by society in general. When Carr stabbed a man to death one night in Morningside Heights, Kerouac helped him dispose of the knife and other evidence, ready to become a criminal himself. He had decided that society's rules were at best meaningless, if not downright destructive, and that friendship was really the only thing that mattered.

After the war and America's so-called victory, which had come

at the price of millions of deaths, Kerouac and his friends were all the more convinced that society's values were bankrupt, and that some kind of new personal code had to be forged. They knew it was the role of the artist to create those new values; but they could no longer figure out what, if any, role the artist and writer might have in modern society, which seemed bent on stamping out individuality in all forms, and seemed to view different behavior of any kind as a red flag of warning.

at the price of millions of deaths, Kerouac and his friends were all the more convinced that society's values were bankrupt, and that some kind of new personal code had to be forged. They knew it was the role of the artist to create those new values; but they could no longer figure out what, if any, role the artist and writer might have in modern society, which seemed bent on stamping out individuality in all forms, and seemed to view different behavior of any kind as a red flag of warning.

Kerouac and Ginsberg, especially, discussed, argued, and pondered what they should do with their lives, what and how they should write, what their proper subjects should be, and so forthâendlessly, in late-night discussions in 24-hour diners and unkempt hipster flats, and in literally hundreds of letters back and forth. Many of these letters have recently been published,

3

and they are often stunningly brilliant, but they also show two young proto-geniuses who have reached an absolute dead end. They comment ad infinitum on books they have read, each other's writings, and every little incident in their rather tame if sordid livesâbut they get nowhere. They reach no resolution. They are looking for a way out and cannot find it.

3

and they are often stunningly brilliant, but they also show two young proto-geniuses who have reached an absolute dead end. They comment ad infinitum on books they have read, each other's writings, and every little incident in their rather tame if sordid livesâbut they get nowhere. They reach no resolution. They are looking for a way out and cannot find it.

And then the answer came to them, in the form of a wild man from Denver blazing across the plains in a stolen carâand later, when the car broke down from being pushed too hard, a Greyhound busâwith his drop-dead-beautiful 16-year-old wife and volumes of Proust and Shakespeare in his small, battered suitcase. The man was 20-year-old Neal Cassady, and his wife was Lu Anne Henderson, whose greatest adventure until recently had been drinking a few beers and smoking a little pot with Neal and his guy

friends and a bunch of other giggling high school girls at a vacant house in the Rocky Mountains just above Denver.

friends and a bunch of other giggling high school girls at a vacant house in the Rocky Mountains just above Denver.

Â

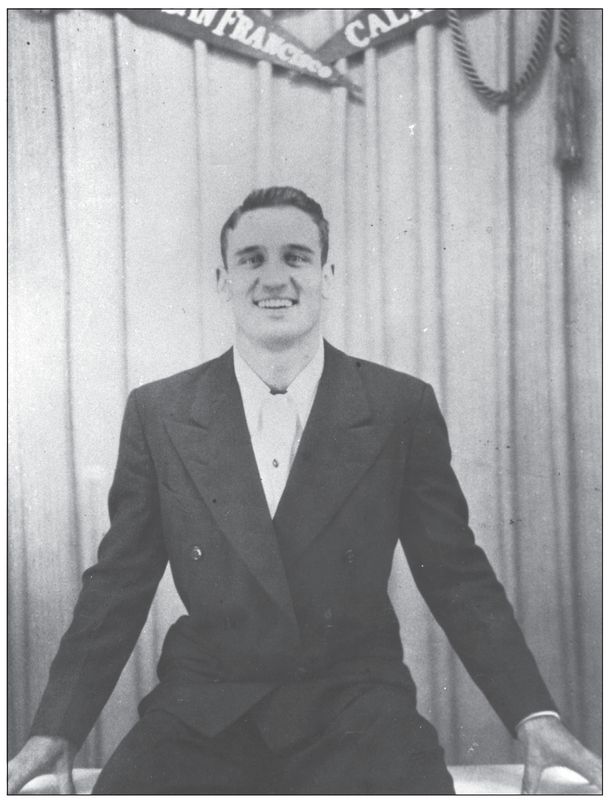

Neal Cassady, San Francisco, circa 1948. (Courtesy of Carolyn Cassady.)

Neal Cassady, however, had lived pretty hard before marrying Lu Anne and dragging her off to New York to fulfill his lifelong dream of becoming a famous writer. (He'd already given up the dream of playing left end for Notre Dame.) Abandoned by his mother when he was sixâin 1932, the depths of the Great DepressionâNeal went to live with his barber father, a far-gone wino, on Larimer Street, the skid row of Denver. He was a sweet kid, a Catholic choir boy for a while, very bright as well as good-looking and athletic. He did his best at school and tried to keep his perpetually drunken father out of trouble. But he was also one of the most highly sexed males on the planet and couldn't keep his hands off female bodies. By his own account, he began sex play with little girls when he was eight, and by the time he was 12 was having sexual intercourse regularly with both girls and grown women.

It wasn't easy for a kid on skid row to find places to have sex, so at 14 Neal began stealing carsâjoyriding it was called thenâwhere he'd grab a car with the keys left in the ignition, or hotwire a car, go pick up his latest girl, whirl her up to the mountains for a quickie in one of those empty houses or cabins he knew so well, and try to get the car back before anyone noticed it missing. He later claimed to have stolen about 500 cars while still in his teens. The problem was that people did notice their cars missing, and Neal was arrested many times. He spent his youth in and out of reform schools, most memorably (and excruciatingly) at the Colorado State Reformatory at Buena Vista, an institution nearly as brutal as an adult penitentiary.

Between skid row and jail, Neal learned that he could enjoy sex with males too. He always preferred his erotic pleasures with women, but men had one distinct advantage: they were usually willing to pay

him for the privilege of a roll in the hay. Before he was incarcerated at Buena Vista, he had worked as a male hustler in Denver. One day he ran across a very powerful gay lawyer and high school counselor named Justin Brierly, who also served as an admissions advisor to his alma mater, Columbia University. Brierly often arranged for his favorite young men, if they were bright enough, to get accepted at Columbia. Brierly was totally smitten with Cassady, and there was no doubt that with his 132 IQ (which Brierly got tested for him) Neal was smart enough to handle college studies. But of course it was not going to be easy, Brierly knew, to get a high school dropout with a long criminal record into an Ivy League school.

him for the privilege of a roll in the hay. Before he was incarcerated at Buena Vista, he had worked as a male hustler in Denver. One day he ran across a very powerful gay lawyer and high school counselor named Justin Brierly, who also served as an admissions advisor to his alma mater, Columbia University. Brierly often arranged for his favorite young men, if they were bright enough, to get accepted at Columbia. Brierly was totally smitten with Cassady, and there was no doubt that with his 132 IQ (which Brierly got tested for him) Neal was smart enough to handle college studies. But of course it was not going to be easy, Brierly knew, to get a high school dropout with a long criminal record into an Ivy League school.

Â

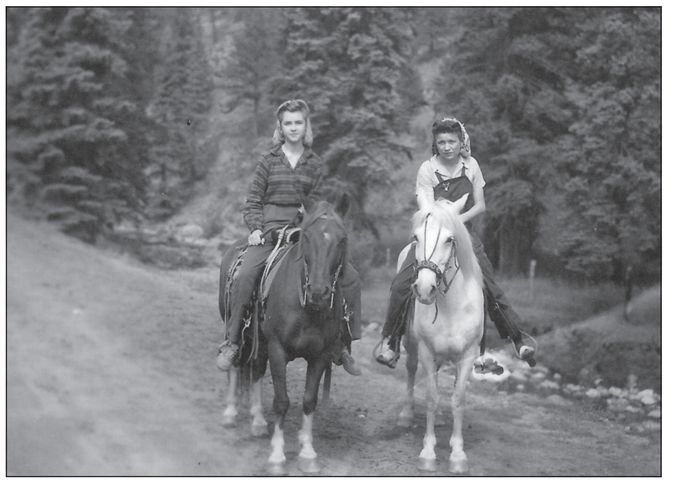

Lu Anne, about age 13, and Dorie (wife of Lu Anne's half brother Lloyd) in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado. (Photo courtesy of Anne Marie Santos.)

Brierly took the tack of introducing Cassady to some of the other young men whom he had helped to become successful students at Columbia, a group that included Hal Chase and Ed White. After corresponding for several months with Neal while he was in prisonâand being highly impressed by Neal's letter-writing abilityâChase met Cassady in person and became close friends with him. Chase also talked about Cassady, and showed Neal's letters around, to his own gang at Columbia, including Kerouac and Ginsberg, who were quite intrigued. Chase went so far as to set up special oral examinations for Cassady with several Columbia professorsâwith the promise that, if he passed, he would be allowed to matriculate there. The exams were supposed to take place in September 1946; but in typical Cassady form, he didn't show up to take them.

Â

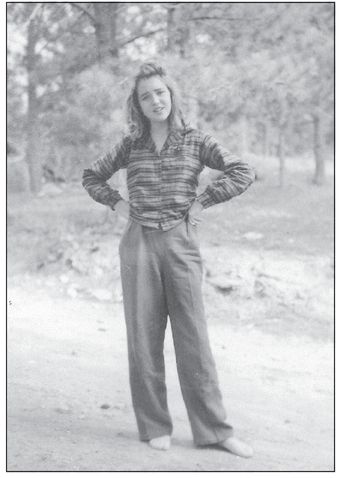

Lu Anne, age 13, in Rocky Mountains near Peetz, Colorado, where her family lived. (Photo courtesy of Anne Marie Santos.)

He did have an excuse, however. Earlier in the year, he had walked into the Walgreens drugstore on 16th Street in Denver with his pool hall buddy Jimmy Holmes and his current girlfriend, Jeannie Stewart, and spotted two girls he didn't know talking in a booth. One of the girls, the blonde, captured his heart and his imagination the instant he saw her. Neal never explained what impressed him so muchâif it were her looks, her animated manner, or the sunshine that almost everyone claimed radiated from her face. In any case, he leaned over to Holmes and whispered, “I'm gonna marry that girl. I don't know her, but she's my idealâthe girl I want to spend my life with.” Jeannie said she knew both the girls from schoolâtheir names were Lois and Lu Anne. Neal suggested that the blonde, Lu Anne, would make a great date for their mutual friend Dickie Reed at a party they were about to have up in the mountains. Neal casually asked Jeannie to go over and get Lu Anne's phone number; and Jeannie, unaware of the treachery, went over and did as he asked.

Three weeks later, Neal did indeed marry Lu Anne. He had no place to live with his new bride, however, nor did Jeannie want to let loose of him. Finding his life far more complicated than he'd ever imagined it could be, by the fall of 1946 Neal had a lot more on his mind than going to college.

Â

Lu Anne:

It all started in October 1946. That's when we took our first trip to New York. Neal and I sort of ran off from Denver because of what happened between Neal and a girl named Jeannie Stewart. She was this girl Neal had been living with when Neal and I met, and she was holding his clothes as a weapon to get him to come back “where he belonged.” She wanted to keep him at her house, and he told her that he wasn't going to do that. So Neal and I went to her house, and he climbed up three stories and broke in the window, and rescued

his clothes and books. His books were the most important thing to him at the time.

his clothes and books. His books were the most important thing to him at the time.

Other books

MEG: Nightstalkers by Steve Alten

The Island by Lisa Henry

Seventh Mark (Part 1 +2) by W.J. May

A Sea of Purple Ink by Rebekah Shafer

The Auditions by Stacy Gregg

Boy Kills Man by Matt Whyman

Dance of Seduction by Elle Kennedy

The New Girl by Cathy Cole

The Fortunates (Unfortunates #2) by Skyla Madi